Angie Sijun Lou is a sixth-year PhD Student in the Literature Department. Lou’s dissertation project, titled Pale Unhappy Dog, is a collection of twelve short stories that explore issues of transnational migration, political upheaval, racial identity, among many others. Lou credits much of her writing to her own family’s history of living undocumented in the United States. As she explains, “they’ve [her family] taught me how to look to the page as a site of permanence when our dreams and labors have been otherwise eclipsed by a state of eternal transit.”

Angie Sijun Lou is a sixth-year PhD Student in the Literature Department. Lou’s dissertation project, titled Pale Unhappy Dog, is a collection of twelve short stories that explore issues of transnational migration, political upheaval, racial identity, among many others. Lou credits much of her writing to her own family’s history of living undocumented in the United States. As she explains, “they’ve [her family] taught me how to look to the page as a site of permanence when our dreams and labors have been otherwise eclipsed by a state of eternal transit.”

In July, we spoke with Lou about her summer plans and her ongoing writing. Lou was named a 2022-23 THI Summer Dissertation Fellow, and participated in THI’s Memory of Forgotten Wars and The Body, Anti(Narrative), and Corporeal Creative Practices research clusters.

Hi Angie! Thank you for taking some time out of your summer to speak to us a bit about your dissertation research and writing. And big congratulations on your THI Summer Dissertation award! To start off, could you please give us a synopsis of your dissertation project? What part(s) of the project are you working on this summer?

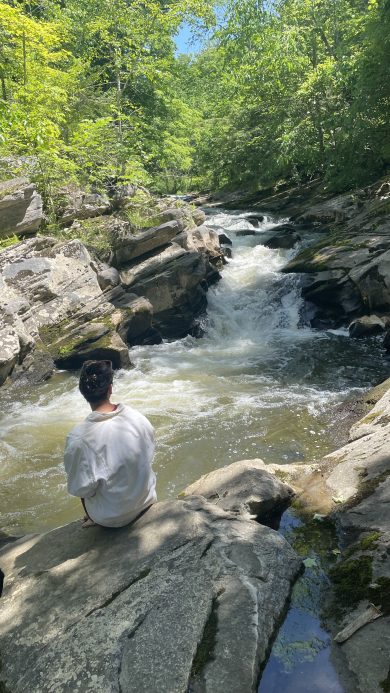

Lou at a writing residency called Millay Arts, where she wrote two of the stories from Pale Unhappy Dog.

Pale Unhappy Dog is a collection of twelve short stories I’ve worked on over the last seven years. It contends with the afterlives of Cold War militarism in Pax Americana, and how those afterlives continue to percolate through China and the Chinese American diaspora. The stories in this manuscript traverse across time and space—they take place in an abandoned fishing village after the Cultural Revolution, a crowded warehouse party in Los Angeles, a pay-by-the- hour motel in suburban Ohio, an electronics factory in the shadow of Mount Emei, etc. The ethos of this project is deeply indebted to my family’s history of living undocumented in the United States; they’ve taught me how to look to the page as a site of permanence when our dreams and labors have been otherwise eclipsed by a state of eternal transit. This summer, I’ve been able to write two new stories and draft the final story in the collection, which I hope to finish writing before the school year begins. It will be my first time holding a complete draft of the book in my hands; I know it will be an emotional moment.

That sounds amazing! It seems like your creative writing project merges in powerful ways with historical analysis and archival research. How do you envision the interplay of history and creative writing in your project? Why is that interaction so important to your work?

I love this question because it makes me think about the role of unknowability in the historical record. In my archival work, I’ve looked for lacunas as speculative openings for narrative possibility. In one story from my collection, I interlace two real narratives. The first narrative is sourced from news reports about the black market organ trade in rural areas in China, how people are tricked into unsafe operations for little money by uncertified doctors. The other narrative is from a documentary about a village where women cut their hair only once a lifetime, a village called Huang Luo in Guanxi Region, now a site for tourists looking for an exotic China before the Cultural Revolution. My goal was to accentuate the dissonance between rapid economic expansion which has dilated the city-rural divide with elements of surreality, practicing a version of what Saidiya Hartman calls “critical fabulation” in the “subjunctive mode” — writing what could have been with invented detail. While social realism has been the popular aesthetic mode for proletariat literature, I try to experiment with opacity, boredom, sublimity, and mysticism.

Your work also complicates and historicizes Chinese American identity in exciting ways. How do you think your project offers new avenues to conceptualize Chinese American identity?

I hope that my stories offer a kind of polyvocalism that destabilize notions of fixed racial identity. Instead of representing a singular Chinese American identity, I hope for this collection to embolden the horizon of possibility for multiple truths, truths which conflict and obscure one another, making space for symbiosis and multiplicity to exist. I believe the collection is less interested in conceptualizing Chinese American identity, and more interested in showing how our diverse experiences of the world are interpolated through the same capitalist processes of domination. I want to take this as the basis of unification, unification over the practices of resistance we engage in toward an abolitionist horizon.

Shifting gears a bit, I also wanted to hear more about your engagement with the Living Writers series. How has this experience influenced your dissertation work and your creative writing more generally?

The Living Writers reading series is such a special program; more students outside of the creative writing concentration should come to these readings. I have been teaching the introduction to creative writing course for the last two years, and it’s amazing to end each week by listening to the writers illuminate how their works are birthed. The title of the series speaks to our department’s commitment to teaching works that speak to what is alive in the literary world now. I believe that language, in its essence, is a collective ritual against fragmentation—the page is a location where we gather and bear witness to each other, testing the boundaries of intimacy and vulnerability. During the pandemic’s virtual ether, this series kept me in touch with this ethos.

Phew! So many big questions, so I thought we could end on a fun note. What are some activities you are most excited about doing during the summer break, and why?

I have the honor of being chosen as a fellowship recipient for the Tin House Writers’ Workshop in Portland, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Middlebury, and the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference in Napa. I am so lucky to spend time in communion with other writers across genres—readings, workshops, and sharing a meal afterwards are what I missed most during the era of social distancing. My other plans include laying in fields, swimming in the ocean, reading poetry to my friends, and looking at the sunset.