Graduate Profile: Raed El Rafei, Film and Digital Media Doctoral Candidate

Raed El Rafei is a filmmaker and PhD student in Film and Digital Media at UC Santa Cruz. Born and raised in Lebanon at the height of his country’s civil war, he has a keen interest in the human stories that lie at the heart of the transformations witnessed in the Arab world in recent years. In October, El Rafei spoke with THI about his life before coming to UC Santa Cruz, his experience as a THI Fellow in the UCSC SSRC Dissertation Development Program, and the complexities of engaging questions around film and queer subjectivity.

You’re a Film and Digital Media PhD Candidate at UC Santa Cruz, and you have also lived a pre-PhD life as a journalist and filmmaker. Can you tell us about your journalism background? What did you cover and where did you write?

I feel blessed that I have been well surrounded in the department and beyond by faculty and peers who are actively thinking of creative ways to produce academic knowledge.

Before joining UC Santa Cruz, I lived in Beirut and worked as a communication officer for a UNESCO project on safeguarding Syrian cultural heritage. Before that, for over ten years, I worked as a reporter for various publications, including The Daily Star and The Los Angeles Times. I was also a freelance producer on video reports and documentaries for TV stations such as CNN, Al-Jazeera, and ARTE. My journalism work focused on Lebanon in political, social, and economic areas. I covered an array of stories like the political uprisings and killings that followed the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in February 2005, the July 2006 Israeli war on Lebanon and its devastating aftermath, civil strife in May 2008, and more recently the different facets of the Syrian refugee crisis. I also worked as a trainer for citizen journalists in Lebanon and Syria and an editor of a weekly online publication by Syrian local journalists as part of a project with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting.

Have these themes carried into your film work? What can you tell us about your filmmaking?

My film work was both a continuation of my reporting career and a reaction to the rigidity of journalistic writing and audio-visual production. I remember one day in 2010 while I was taking a break from work as a researcher and co-director on a documentary for Al-Jazeera about the history of student movements in Lebanon, it hit me how much I wanted to break free from the TV documentary format and work on a creative film project.

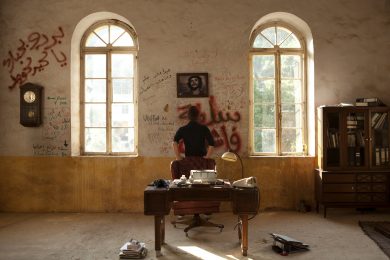

My sister, Rania, who is also a filmmaker, and I started researching the 1974 occupation of the American University of Beirut by students, which was an incredible moment of struggle for political change and social justice. The massive street protests and the toppling of dictators that swept through the Arab region in 2011 motivated us to frame the 1970s leftist uprisings with keen attention to the historic moment of the Arab spring. We collaborated with young Lebanese political activists to create film work based on improvisation about the meanings of revolution and change. This collaboration culminated in 2012, when we made the hybrid (fiction/documentary) film, 74 (The Reconstitution of a Struggle), that was screened in international film festivals. We were inspired by directors like Jean-Luc Godard and Peter Watkins to think about how past historical events imbued the present moment with ideas and affects, especially in a country like Lebanon that sustains a problematic relationship with its past and specifically the memories of the civil war (1975-1990).

After that project, I continued experimenting with form in film but I turned my attention inward and made an intimate, autobiographical essay documentary that questioned the politics of borders (both physical and imagined) between Europe and the Middle East. I wanted to reflect on a transnational gay love story at a moment when European mainstream media projected a limited and condescending vision of the Middle East as a source of conflicts and an “exporter” of refugees. The film, Here I am … Here you are, was screened in October 2017 at the San Francisco Arab Film Festival.

How have these experiences shaped your PhD so far?

When I started my project-based PhD program in the Film & Digital Media Department, I felt that I had an array of experiences and know-how to inspire my work. But I realized that I needed to put a lot of effort to become comfortable with theory. Navigating both artistic, creative filmmaking impulses and rigorous academic writing was a challenge. But I feel blessed that I have been well surrounded in the department and beyond by faculty and peers who are actively thinking of creative ways to produce academic knowledge. I particularly feel inspired by feminist approaches to critical thinking and non-linear, affective essayistic writing and production methods.

You’re a fourth-year PhD candidate, and you recently completed your qualifying exam. Can you tell us about your research? How do themes of queerness, space, and urban spatiality feature in your academic work?

I feel that in the past ten years, Arab and Muslim artists and filmmakers have engaged, boldly and creatively, with questions surrounding queer subjectivity. Their works and practices feature multi-layered ways of representing sexuality by bringing to light taboo issues surrounding the body and deconstructing social and bio-political patriarchal systems of control and power. But they also call into question western and neo-liberal notions of queer subjectivity. Resisting narratives of queer identity as mainly a human rights issue linked to personal choice and self-discovery, I think that artists in the Arab region and beyond have produced counter-narratives that fold questions of sexuality into complex historical, political, social, economic and environmental frameworks. They have linked queer subjectivities and practices to issues like the Arab-Israeli conflict, post-colonial nationalism, western-backed dictatorships, Arab-spring uprisings, Islamophobia and the war on terrorism, for example. Many of these artists are also contributing to the formation of fascinating “queer imaginaries” by tapping into Islamic and pre-Islamic mythologies, as well as concepts from non-western philosophies and cultures.

My research looks at historical, archival, fictional, speculative, and utopian approaches and tendencies in the art and film works of some of these contemporary Arab and Muslim queer artists. I am particularly interested in how emerging queer imaginaries in the Arab region complicate contemporary notions of subjecthood within the nation-state but also with respect to the world.

In my writing and film work, I’ve been exploring queerness in the realms of unknowability and affect specifically in my hometown, Tripoli, Lebanon, a marginalized Middle Eastern city often described as conservative and a hotbed for Islamist ideologies. I’ve been exploring the city of Tripoli itself with its palimpsestic physical layers as a queer space of unproductiveness, marginality and failure thinking, for instance, through notions of queer temporality, spatiality and failure in the work of Jack Halberstam or engaging with José Esteban Muñoz’s concept of “queer utopia” in the context of the Middle East, which is often represented as a place of tyranny, homophobia and dystopia. I’ve attempted, for instance, to translate into a film essay Sara Ahmed’s invitation in her book Queer Phenomenology to think about “orientation” in sexual orientation, using my camera “to deflect, pervert and turn away from the straight lines of normative textuality.” I’ve also looked at public spaces, specifically the public garden of Tripoli, as a liminal space of slippages and ambiguities, to think of a queer aesthetic in the Middle East “in new ways” and “other-wise”, as queer theorist Teresa de Lauretis proposed.

My research looks at historical, archival, fictional, speculative, and utopian approaches and tendencies in the art and film works of some of these contemporary Arab and Muslim queer artists.

You received a 2019-2020 UC Santa Cruz SSRC grant to help you develop your dissertation proposal. How did the Dissertation Proposal Development program support your project?

The grant was very useful in that it allowed me to think more critically about my project. The many fruitful conversations I had with (and feedback I received from) faculty and other PhD students from outside my field helped shape my project in more accessible and clearer terms.

Where can we find some of your film work and articles?

In September, The Common literary magazine published one of my essays titled, Fragments of Shame and Pride. For my other written and film work, you can look at my website: www.raedrafei.com where I try as much as possible to have comprehensive and up-to-date information.

Raed El Rafei is also affiliated with the Center for the Middle East and North Africa at UC Santa Cruz, which will be hosting a screening of Sansour and Lind’s In Vitro on December 2 and an event with Lawrence Abu Hamdan on January 22nd.