Graduate Profile: Thaïs Miller, Literature Doctoral Student

Thaïs Miller is a PhD Candidate in the Literature Department at UC Santa Cruz. Miller is part of the department’s Creative/Critical Writing Concentration, and was the recipient of a THI Summer Graduate Research Fellowship in the 2020-2021 cycle.

In December, we spoke with Miller about her work, current projects, and experience as a THI Fellow. In her own words, she “writes fiction, book reviews, peer-reviewed academic articles, poetry, plays, screenplays, and dialogue for robots.” We discussed her research interests and learned about her experience last summer with the Uriel Weinreich Summer Program in Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture at YIVO.

Thanks for taking the time to speak with us, Thaïs! Your work sounds absolutely fascinating. Can you give us an outline of your interests? How do you think about your scholarship?

I’m interested in 20th– and 21st Century Jewish novels, short stories, films, television, and digital media with a focus on Jewish humor.

As a writer who is also Jewish, American, a woman, and attempting to infuse my fiction with comedic elements, my work is deeply personal. I am investigating my community’s complex and fascinating history, especially within Los Angeles where I grew up. I feel a responsibility to care for the history and memories of the community that fostered my education. I am studying the women writers and performers, who were so often dismissed and marginalized, who paved the way for me, and I hope that by reclaiming their legacies, I’m paving the way for the next generation.

The Creative/Critical Writing Concentration is such an innovative intellectual space at UCSC. How has being a part of it influenced your work? Has your work or focus shifted since you arrived at UC Santa Cruz?

The Literature Department’s Creative/Critical Writing Concentration has had a wonderful influence on my work as well as my process. There are a few specific examples that I’d like to share.

My professors in the Creative/Critical Writing Concentration convinced me to completely redesign my daily routine to prioritize my writing and protect my time to be creative. Now I write every day.

I entered the program with two completed novel manuscripts. Professors Karen Tei Yamashita and Micah Perks (my advisor) helped me discover that instead of writing about two sets of characters during two separate periods in Los Angeles’ vibrant history, I was actually writing about several generations within the same family. I’m currently writing one new novel about this family.

“Hobbies” that I thought I was pursuing “on the side” became my main focus. Believe it or not, the summer before I entered UCSC’s program, I had been presenting on the Netflix show GLOW at academic conferences, just because I found the series fascinating. My professors, especially Professor Dorian Bell, convinced me that everything I was doing “for fun” should actually be at the core of my dissertation project.

I reconnected with my roots. For a long time, I’ve been interested in studying historiography, the ways that historical narratives are written and legacies formed, especially the ways that they can be manipulated, altered, and revised in fictional works. The more time that I spent in the program, the more I realized that I was entering the program with a wealth of very specific knowledge about fiction, film, television, new media, feminism, and Judaism. All of my professors in the concentration strongly encouraged me to lean into my knowledge base, my obsessions, and my personal background. I never planned to pursue research related to Jewish Studies, but UCSC has such a fantastic Jewish Studies program that I couldn’t help myself. Professor Perks introduced me to more professors who teach within the Jewish Studies Program, including Professor Nathaniel Deutsch, the director of THI, who is serving on my dissertation committee. I also developed a love for learning Yiddish at UC Santa Cruz, where I began taking Yiddish courses for the first time in the winter of 2019 with Professor Jon Levitow (whom in Yiddish I call “Reb Yankl”).)

My professors helped me rediscover the joy in scholarship.

Your project, “Vaudeville to GLOW: One Hundred Years of Jewish Humor, Jewish Women, Trauma, and Discrimination in Los Angeles,” sounds really intriguing. Can you give us something of an overview of what you’re working on here? What’s at stake in this project?

When most people think of the incredible contribution that Jewish writers and performers have made to American popular culture, they think of a “boy’s club,” for example, Philip Roth, Woody Allen, and Mel Brooks. Jewish women have been ignored in this regard, despite their significant and long-lasting influences. This narrative of the “boy’s club” demeans the role of women writers and performers. A lot of my work aims to deconstruct and rewrite this narrative, to undo the harm that has already been done. I grew up reading primarily male authors and learning primarily about male performers. I didn’t read the work of major Jewish American women writers until I was in graduate school!

Often, Jewish writers use humor to critique the social system around them and highlight ongoing persecution. Jewish humor serves as a tool of criticism and resistance. Numerous scholars from Sigmund Freud to Jeremy Dauber have also discussed how Jewish humor is often directly responding to experiences of antisemitism and trauma as a defense mechanism.

New York City has often been seen as the epicenter of Jewish cultural contributions while Los Angeles is often slighted even though it had an even more important role in broadcasting and distributing the work of Jewish American writers and performers globally. I am interested in how the Jewish community’s physical presence and socioeconomic status within Los Angeles has changed over the past century. Jewish Angelenos, like other minoritized groups, were initially victims of severe housing discrimination that kept them from living in many neighborhoods. As Jewish humor became increasingly popular and mainstream in the Hollywood film industry, however, their socioeconomic status and their racialized status changed. In each decade from 1919 to 2019, Jewish humor reflects the Jewish-Angeleno community’s indeterminate status and connection to traumatic events. Often Jewish humor transmits local experiences globally.

I am fascinated by the transmission of trauma through humor. Women, according to scholar Marianne Hirsch, are more likely to be involved in the transmission of trauma from one generation to the next. Women writers have too often been sidelined in Jewish humor studies. Jewish women comedians, once belittled, are experiencing a contemporary renaissance. My research aims to analyze the relationship between their humor and the transmission of trauma and to understand their work within the unique historical context and geographic landscape of the Jewish-Angeleno community.

Jewish Film and New Media recently published my peer-reviewed academic article, “Representations of Refuseniks and Soviet Jewish Emigration in GLOW: Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling,” which also explores the relationship between women writers and performers, Jewish humor, and inherited trauma.

I’m currently developing a new literature course based on my research tentatively called “‘Funny Girls,’ 100 Years of Jewish American Women Writers and Performers.”

This past summer you were selected as a 2020-2021 THI Summer Research Fellow. To be sure, COVID complicated everyone’s plans, but what have you been working on and thinking about over this last summer?

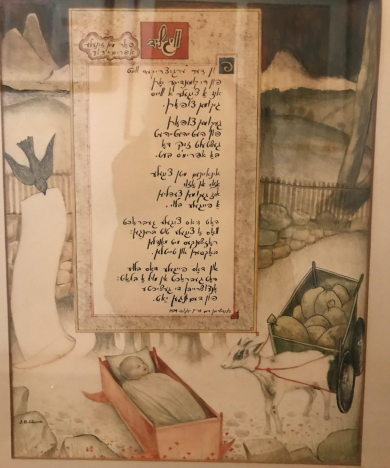

The Summer Graduate Research Fellowship I received through the Humanities Institute enabled me to virtually attend the Uriel Weinreich Summer Program in Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture at YIVO. While I was not able to visit the world-renowned Ashkenazi cultural institute, library, and archive in person in New York City, I was able to attend intensive Yiddish language and literature classes via Zoom, Monday through Friday, for an average of seven hours a day for seven weeks this summer. I read and discussed the works of numerous authors in Yiddish. My courses paid special attention to women writers in Yiddish. We analyzed the works of Glikl of Hameln, Anna Margolin, Celia Dropkin, and Blume Lempel, among others in Yiddish. These courses improved my Yiddish language skills, so I am now able to read (and more quickly translate) more primary materials in their original regional orthography. I also gained access to YIVO’s and the Yiddish Book Center’s extensive, helpful virtual resources. I learned a great deal about Ashkenazic Jewish history as well as Yiddish literature, film, theater, dialects, cuisine, and culture from experts in the field.

On October 9, I read a chapter from my dissertation novel at “Zoom Forward! Reading 33,” an ongoing reading series to showcase writers, keep our cultural spirits high, and support Bookshop Santa Cruz. The chapter I read is called “YouTube Yiddish.” It specifically discusses Yiddish literature, including the work of Glikl of Hameln and Blume Lempel, women writers whose work I was first exposed to this summer.

Thanks to my experiences this summer, for example, I was hired as a Yiddish consultant for Jonathan A. Goldberg’s fictional, dramatic, and humorous podcast “The Landwhale Murders,” currently in production. I was solicited (and able) to translate a Yiddish poem by Aleph Katz upon special request from his family. I have also been able to make progress organizing and translating my family’s archive of Yiddish letters and documents.