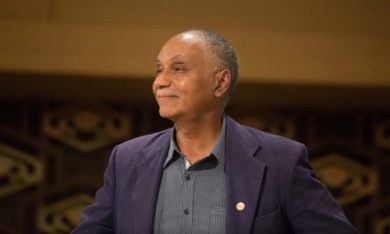

Tyler Stovall, Renowned History Professor And Former Humanities Dean, Dies At 67

Tyler Stovall, a renowned historian, professor, and former Dean of Humanities at UC Santa Cruz, died Dec. 10, 2021 at his home in New York City. He was 67.

Stovall was the author of 10 books and various articles on modern French history, with a focus on labor, colonialism, race, with his latest—White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea—published in early 2021. Stovall was a faculty member of the UC Santa Cruz Humanities Division for 13 years, including three years serving as the chair of the History Department and provost of Stevenson College. His tenure as Dean of Humanities at UC Santa Cruz lasted from 2014-2020.

“An insightful scholar and author dedicated to social justice and the advancement of minority scholars, Tyler touched the lives of countless students, faculty and staff in his nearly two decades on our campus,” Chancellor Cynthia Larive and Campus Provost and Executive Vice Chancellor Lori Kletzer said in a joint campus message. “We knew Tyler as a skilled educator and as a thoughtful, generous, and kind colleague. He will be missed tremendously.”

In addition to his time at UC Santa Cruz, Stovall’s long and distinguished career found him serving as president of the American Historical Association and as a visiting professor at the Université de Polynésie Française in Tahiti, as well as taking teaching positions at Ohio State University and as both a professor of French history and dean of the Undergraduate Division of the College of Letters and Science at UC Berkeley. At the time of his death, Stovall was serving as dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Fordham University in New York City.

“A man of deep conviction and penetrating insight, Tyler was a great mind, a great heart, and a kind and generous colleague,” Joseph M. McShane, S.J., President of Fordham University, said in a statement. “He came to Fordham in July 2020, and during his too-brief tenure brought tremendous intellectual acumen, energy, and gravitas to the role. He was an experienced and capable administrator and a highly regarded historian and public intellectual with a fierce commitment to social justice and the advancement of minority scholars.”

Stovall was among the first African Americans in the U.S. to achieve prominence as a European history scholar, and he provided encouragement and mentorship for other minority scholars. He spoke eloquently throughout his career about the importance and value of diversity, noting that while people often talk about diversity as being important for marginalized communities, it is something that benefits all of us. “Being exposed to people from different backgrounds, being able to interact with people with different experiences is something that we all learn from and it makes all of our lives better,” he said in a short video on excellence and diversity produced by Fordham University earlier this year.

Stovall was born on Sept. 4, 1954, in Gallipolis, Ohio to parents Tyler and Barbara Stovall. His father was a child psychologist, and his mother directed the South Side Settlement House, a community center in Columbus, Ohio. Both of Stovall’s parents were active in the growing civil rights movement, with activists and guests of their local NAACP chapter visiting their home regularly. Their efforts inspired Stovall’s own political activism, including joining a Race Relations Club at his public high school and giving his first public speech against the war in Vietnam at age 18.

Stovall attended Harvard, graduating cum laude with a degree in history. He continued participating in antiwar and anti-racist protests and was, at one point, attacked on a public street with acid sprayed in his face. It thankfully didn’t cause any physical damage. He went from Harvard to graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where he narrowed his interest in European history to modern French history under the tutelage of noted scholar Harvey Goldberg.

Stovall soon earned awards and grants that allowed him to pursue his research into working class neighborhoods in Paris’s suburbs, in particular the work being done to turn citizens frustrated with the sanitation and water systems into a vibrant electoral base. This resulted in his 1984 dissertation, “The Urbanization of Bobigny,” which was eventually revised and published in book form as The Rise of the Paris Red Belt by the University of California Press in 1990.

After earning his PhD in modern European/French history in 1984, Stovall continued to research his dissertation, earning a fellowship that took him to UC Berkeley. It was there that he met Denise Herd, a fellow scholar whom he married in 1988. That same year, Stovall took a position in the history department at UC Santa Cruz where his courses homed in on race and ethnicity in Europe and modern France.

In 1996, Stovall made a splash with the publication of his book Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light, a work that explored the lives of the many Black writers, artists, and performers from America whose work flourished after emigrating to France in the 20th century. The book was praised as “an engaging chronicle of African-American life in Paris since the dawn of the Jazz Age,” by Kirkus Reviews. The book also served as vital source material for Myth of a Colorblind France, a 2020 documentary film for which Stovall was interviewed.

His most recent book White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea earned Stovall even more attention and acclaim. Numerous critics connected the book’s theme that, as Stovall writes, “at its most extreme freedom can be and historically has been a racist ideology,” with the January 6 attack on the U.S. capitol. “White Freedom has much to tell us… about how racism has been built into so many of our systems and institutions, and about how what we see as freedom isn’t really freedom at all,” wrote Brock Kingsley in a piece written for Chicago Review of Books.

“For me, Tyler should be remembered as a scholar who firmly believed that the writing and teaching of history was a political act,” said Michael Vann, professor of history and Asian studies at California State University, Sacramento, who studied under Stovall for his PhD at UC Santa Cruz. “Throughout his long and vibrant career, Tyler used his path breaking research, critical analysis, and engaging lectures as weapons in the fight for social justice. Despite studying some of the worst aspects of human behavior, he always remained optimistic and held that a better world was possible, and that education was central to that goal. I’m heartbroken to lose him as a friend and a mentor, but also as a role model in our unfinished struggles.”

In addition to his wife, Denise Herd, Tyler Stovall is survived by their son, Justin; and a sister, Leslie Stovall. Information on services will be provided when available.

Original Link: https://news.ucsc.edu/2021/12/in-memoriam-tyler-stovall.html.