Imagination Series: E. Hande Tuna in Conversation with Paul Guyer

E. Hande Tuna is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at UC Santa Cruz and is affiliated with the Feminist Studies Department. Prior to arriving in Santa Cruz, Tuna completed postdoctoral research at Brown University funded by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). Tuna received a PhD from the University of Alberta and studies contemporary issues in value theory, in particular moral psychology and aesthetics, and on the history of these fields. Tuna has authored multiple papers on Kant and his views on beauty, music, and artistic criticism. At UC Santa Cruz, Tuna teaches courses on feminist philosophy, early modern women philosophers, and philosophy and fiction. Tuna also helped develop THI’s Questions That Matter course on Imagination and served as a faculty mentor to the Graduate Student Instructors teaching that course in the Spring 2022 quarter.

E. Hande Tuna is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at UC Santa Cruz and is affiliated with the Feminist Studies Department. Prior to arriving in Santa Cruz, Tuna completed postdoctoral research at Brown University funded by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). Tuna received a PhD from the University of Alberta and studies contemporary issues in value theory, in particular moral psychology and aesthetics, and on the history of these fields. Tuna has authored multiple papers on Kant and his views on beauty, music, and artistic criticism. At UC Santa Cruz, Tuna teaches courses on feminist philosophy, early modern women philosophers, and philosophy and fiction. Tuna also helped develop THI’s Questions That Matter course on Imagination and served as a faculty mentor to the Graduate Student Instructors teaching that course in the Spring 2022 quarter.

Imaginative Resistance

In the prologue he wrote to Adolfo Bioy Casares’ brilliant novel, The Invention of Morel, Jorge Luis Borges comments on the inventiveness of fiction. Borges writes, “The Russians and their disciples have demonstrated, tediously, that no one is impossible. A person may kill himself because he is so happy, for example, or commit murder as an act of benevolence. Lovers may separate forever as a consequence of their love.”

Can we always follow characters down their rabbit holes or are there limits to our willingness to do so?

Yet, psychological novels, he adds, must also be realistic. There must be a reason, a reason that will satisfy us, for a man to kill himself because he is so happy. There are also other types of fictional works that do not attempt to transcribe reality. Our imagination expands as we read or watch novels or movies involving people controlling energy, creating/stopping earthquakes, earthlings being replaced by alien-human hybrids with big eyes, little girls taking pills that make them larger or smaller. Can we always follow characters down their rabbit holes or are there limits to our willingness to do so? One of the best things about fictional works is that they help us to picture all kinds of stories about experiences we have never had and we can envision futures that have yet to manifest, to imagine things that we cannot otherwise imagine. Philosophers have explored how moral and ethical values can prohibit us from fully immersing ourselves in the imagined worlds of others, especially when a work prompts us to imagine that something we believe to be wrong is actually right, such as genocide, rape, or infanticide. Fiction becomes unimaginable at that point; we cannot accept those things which transgress so forcefully against our values. E. Hande Tuna, UC Santa Cruz assistant professor in Philosophy, is an expert on “imaginative resistance” — the moment when we are no longer able to play along in imaginative activities prompted by works of fiction or speculation.

In the following interview, Professor Tuna (EHT) explores the concept of imaginative resistance with Professor Paul Guyer (PG), Jonathan Nelson Professor of Humanities and Philosophy at Brown University. Certain themes emerged from their conversation that we want to highlight as we work through the exciting complexity of imaginative resistance.

Their discussion of imaginative resistance raises important questions, including: To what extent does the way that a story is written or told affect our ability to imagine? Does the author and their process of creating a work of fiction impact our ability to imagine the content? Can we put our trust in authors who write on the lived experiences of social groups to which those authors do not belong? Do we as consumers of fiction have a moral responsibility to refuse to imagine some things? Is it a good thing that our imaginations have limits?

EHT: This year the UC Santa Cruz Humanities Institute chose Imagination as the annual theme for their Expanding Humanities Impact and Publics project. To contribute to this project, I am conducting a series of interviews on imagination. The starting point of these interviews is a very specific question. Have you ever had an experience of the sort that the philosophers and psychologists refer to when they use the term “imaginative resistance”? So my question to you then is whether you ever had such an experience where you felt you cannot or will not engage in the imaginative activities prompted by a work of fiction?

PG: I hate horror movies and many kinds of crime movies. To enjoy either one requires a certain kind of separation from both moral principles or in psychological terms perhaps moral scruples that may apply, particularly in the case of crime narratives or also more physiological risk aversion, which might apply more in the case of horror movies.

I identify strongly with depicted characters, whether in reading or in watching. My wife always puts that by saying, I fail to distinguish between fact and fiction. At the cognitive level, I do not fail to distinguish between fact and fiction. I know perfectly well what is a fiction or fictional narrative and what is nonfiction. But nevertheless if the character is well presented– aesthetically well presented, well acted, well produced, whatever, then I feel strong identity or strong aversion. So I can have imaginative resistance or I can have whatever the opposite of that would be, perhaps imaginative identification.

Bill Dobson, an English professor in the fictional Netflix series The Chair, who makes a series of painful mistakes that jeopardize his academic career. |

PG: We watched two things recently. The first one is a Netflix series, The Chair. You know this one?

EHT: Yes, I watched it. I think more or less all the academics watched it.

PG: I kept thinking that Bill, [he’s] just being such a schmuck. And right from the beginning– oh, yes, he lost his wife and so on. His judgment is not in good shape. But he was getting too involved with the student Daphna right from the beginning. Even apart from the Nazism business, anyone who works in the university has to know that was going to lead to trouble.

And I could, of course, if I had a certain kind of compartmentalizing mind and I might just said, “OK, that’s the premise of the show, the trouble needed for dramatic purposes.” But I’m sitting there and yelling, probably even out loud: “Don’t do that, you idiot!” Step back and blah, blah, blah. So you know there were enough other highly entertaining things about that series, so it didn’t lead me to simply turn the TV off or go to a different room. But it interfered with my enjoyment of the show.

To what extent can we inhabit the imaginative worlds of creators who we find morally reprehensible? What do we do with the great work of morally suspect people? |

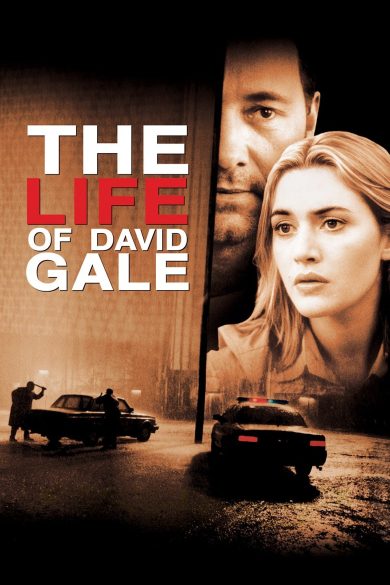

PG: The second thing we watched recently was a movie [referring to The Life of David Gale] in which Kevin Spacey plays another college professor. In this case, I didn’t like the movie. I didn’t watch most of it. But I think in this case, it might have had to do with my aversion to Kevin Spacey, the actor as opposed to any of the characters or the situation. And that would require a different category, but it not. That’s not imaginative resistance exactly what– do you have a category for that?

PG: The second thing we watched recently was a movie [referring to The Life of David Gale] in which Kevin Spacey plays another college professor. In this case, I didn’t like the movie. I didn’t watch most of it. But I think in this case, it might have had to do with my aversion to Kevin Spacey, the actor as opposed to any of the characters or the situation. And that would require a different category, but it not. That’s not imaginative resistance exactly what– do you have a category for that?

EHT: Yes, it is different. You’re rejecting the work, but not because of your ethical qualms about the movie. You are resisting due to the perceived moral problems with the actor himself.

PG: Right. So it’s closer to the case in which you object to a work because of something you believe about the author, even though it is not manifest in the work or it’s not any part of the diegetic of the work. For example, Roald Dahl. Roald Dahl’s books are wonderful for children and pre-teens. But we know that Roald Dahl was mean to women. He was not a nice guy. And it’s hard to put that entirely out of your mind. But if the work is wonderful enough like The Twits or Matilda or any of those great Roald Dahl books, you can actually put that out of your mind, or at least I can put that out of my mind in a way in which you cannot put it out of your mind if it is diegetically present in the work itself.

What happens when the context around a fictional situation changes? Or, when fiction becomes reality, does this change the ways we resist imagining what is depicted? |

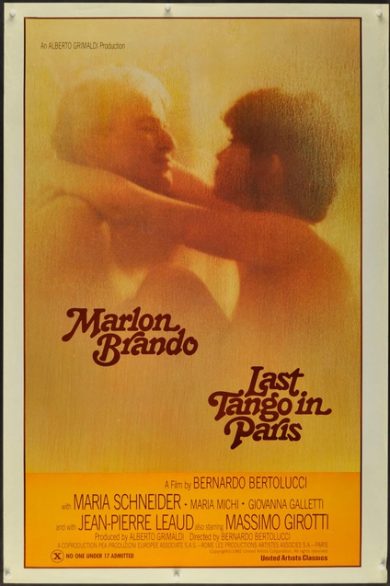

Example: The 1972 film Last Tango in Paris, starring Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider, received critical acclaim. However, decades later, the film’s director Bernardo Bertolucci admitted that the infamous rape scene in the film, in which Brando uses butter as lubricant and then forces himself on Schneider’s character, was not scripted or agreed to by Schneider. |

EHT: Sometimes the aversion towards the actor or the director is completely not external to the work, like in the Last Tango in Paris. That movie was loved and admired for a very long time. And then we learned that Schneider was never informed about the butter scene. She will describe the experience by saying that she felt raped. That changes things, right? Our perspective switches. The moral blameworthiness of Marlon Brando, the actor, and Bernardo Bertolucci, the director, directly affects our perception of the movie.

EHT: Sometimes the aversion towards the actor or the director is completely not external to the work, like in the Last Tango in Paris. That movie was loved and admired for a very long time. And then we learned that Schneider was never informed about the butter scene. She will describe the experience by saying that she felt raped. That changes things, right? Our perspective switches. The moral blameworthiness of Marlon Brando, the actor, and Bernardo Bertolucci, the director, directly affects our perception of the movie.

PG: I am not sure if it is a different case really. If we’re watching a sex scene, well, we can make several different assumptions. We can assume that it is simulated sex. And then we can enjoy it or not. But then our attitude will be based on how much we like watching people have sex or dislike watching people have sex. We could assume that it is real sex going on, but that it was voluntary. And then we might be in the same place as we were before. It’s voluntary, so we don’t have any moral objection to it.

Or we might soon realize, whatever that was, it was not actually consensual. And then, presumably for most people, I think imaginative resistance would kick in, but it wouldn’t really be fundamentally different from imaginative resistance to a work because of our beliefs about the moral turpitude of the director or the actor or somebody involved.

The difference would just be that in this case, the moral turpitude was directly involved in the production of the thing. And it was literally filmed for us, whereas in the other cases the moral turpitude might not be involved in the production or the work itself, but might be something elsewhere in the life of the relevant person, the actor, director, whatever it is.

Now, I take it that imaginative resistance is a psychological phenomenon where we are unable to separate appreciation of the work from our responses to some moral issue. It can be a diegetical moral issue, a moral issue with the content of the work. Or it could be an extra-diagetical moral response to some aspect of the life and conduct of somebody involved in making the movie or the book, whatever it is.

Another example that encourages us to consider whether the process of imaginative creation matters at all to our reception of a creator’s work is a series of paintings by Renaissance painter Rafael. In The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia and various depictions of the Virgin Mary, Rafael used his mistress as a model to paint saints and other holy figures. |

PG: [Rafael] used his mistress as a model for painting female Saints. Nevertheless, it’s a picture of the Saint, not a portrait of his mistress. In reality, he created [the painting] by painting a portrait of his mistress, but in the art world and its framework, it is actually a painting of a Saint. So how the thing is made– this is the point–how the thing is made is not necessarily part of its content. In other words, it could still be that in the movie [The Last Tango in Paris] what is being depicted is consensual sex. What we’re viewing at one level, diegetically, is not sexual assault, although, of course, we are viewing a sexual assault. It’s not a depicted sexual assault. It’s a depicted act of consensual sex. But in fact, it was sexual assault. Just like Rafael’s painting is, in fact, a portrait of his mistress, but it’s not a depiction of his mistress. It’s a depiction of the Saint.

It’s a question of how your knowledge of what is going on affects your response to the depiction or the fiction. It’s not a cognitive question. It’s an emotional question. Some people make a very strong emotional distinction between responding to the depiction and responding to whatever they know about how it was produced. Other people like me make a much weaker distinction. That’s the flip side of emotional identification that makes it possible to enjoy the fiction. That’s dependent upon identification with the characters. It may be true that certain kinds of characters you can get emotionally involved with in a very positive way. And other kinds of characters you get emotionally involved with in a negative way. That may rise to the level of blocking any enjoyment of the work at all, leading you to get up and leave the room or turn off the TV set or whatever.

EHT: In these cases, the person seems to compartmentalize in a certain sense.

PG: Your judgments may be compartmentalized, but your feelings are not compartmentalized. You can make an aesthetic judgment about the formal qualities of the fiction. And you can make a moral judgment about the content, or about the real-life people in production. The point is you can distinguish those modes of judgment and a particular person may be able to compartmentalize at the level of judgment. And then may or may not compartmentalize at the level of emotion. Some people do compartmentalize more at emotions. Some people compartmentalize less. I make strong cognitive distinctions, but don’t compartmentalize my emotions very much. Therefore, I can’t stand watching various of the things that my wife watches. She makes strong cognitive distinctions and strong emotional distinctions also.

EHT: Thank you so much for taking the time to the interview. This was a real pleasure to talk to you about imaginative resistance.

PG: You’re very welcome and good to see you.

Concluding Thoughts

In this interview, we have used examples from film, literature, and art to think about the ways that both imaginative content and the process of making such content influence our reception (or rejection) of certain imagined worlds. Although we often reject the imaginative work of people we have moral qualms with, our degree of resistance often depends on how we relate to the characters and the people who portray or create them, and the completeness of our knowledge about how certain imaginative works were produced.

“Imaginative Resistance” is part of The Humanities Institute’s 2022 Imagination Series. This series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti in the Humanities community at UC Santa Cruz – each of whom highlight connections between imagination and their work or consider the role of imagination in fashioning new worlds. Throughout Spring quarter, be sure to look for these amazing essays in our weekly newsletter!