Grad Profile: Jonathan Van Harmelen

Jonathan Van Harmelen is a PhD candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. Van Harmelen’s research explores the role of Congress during and after the Second World War in shaping policies concerning Japanese-American incarceration. In October, we learned more about Van Harmelen’s ongoing research and public humanities work. Van Harmelen received a 2022 THI Summer Public Fellowship to work with Densho, a nonprofit dedicated to documenting the stories of Japanese Americans who were unjustly incarcerated during World War II. You can read Van Harmelen’s entries for Densho here. He also received a 2022 THI Summer Research Fellowship to support his archival research in California and Missouri. We discussed Van Harmelen’s archival work and the relationship between public history projects and academic research.

Jonathan Van Harmelen is a PhD candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. Van Harmelen’s research explores the role of Congress during and after the Second World War in shaping policies concerning Japanese-American incarceration. In October, we learned more about Van Harmelen’s ongoing research and public humanities work. Van Harmelen received a 2022 THI Summer Public Fellowship to work with Densho, a nonprofit dedicated to documenting the stories of Japanese Americans who were unjustly incarcerated during World War II. You can read Van Harmelen’s entries for Densho here. He also received a 2022 THI Summer Research Fellowship to support his archival research in California and Missouri. We discussed Van Harmelen’s archival work and the relationship between public history projects and academic research.

Hi Jonathan! Thanks for chatting with us about your public fellowship work and your ongoing research and writing projects. To begin, could you give us a general synopsis of your dissertation project, and more specifically, the research you conducted this summer?

Thank you for inviting me! My dissertation, “Legislating Injustice: Congress and the Wartime Incarceration of Japanese Americans,” focuses on Congress and its wartime and postwar role in the incarceration of Japanese Americans. This story is generally told as a story of broad executive powers, while the role of the legislative branch is greatly understudied. Yet throughout World War II, Congress was one of the key actors. Congressional leaders pushed for forced removal. A number of different members of Congress held hearings that examined the question of how to coordinate the forced exodus of Japanese Americans from the West Coast and their resettlement throughout the United States. During the postwar years, Congress repeatedly examined the issue of “rehabilitating” Japanese Americans into American society, and passed legislation allowing Japanese immigrants to become U.S. citizens and an early form of compensation for families affected by the incarceration. This summer, my research centered on Congressional action regarding the return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast during the late 1940s.

You spent time this summer doing research at the Bancroft in Berkeley, the California State Archive in Sacramento, and the Truman Library in Independence, MO. Could you share a little about your process as an archival researcher? I’m curious whether the medium affects your method. For example, do you take a different approach when reviewing transcriptions of Congressional proceedings versus, say, reading through President Roosevelt’s correspondence? When, for you, does a historical document come alive?

Great question. Doing archival research can be both a thrilling and challenging experience: thrilling in the sense that you might find that one document that changes your perspective on a project, and challenging in how bureaucratic archival procedures can be. Because of COVID guidelines, securing appointments at the archives continues to be a hurdle for scholars hoping to return to full-time research. I have been fortunate enough to get in to do research at archives, and also to request scans from other facilities, all of which has helped me offset pandemic-related restrictions. For example, I spent this summer visiting the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley and the Harry S. Truman Library in Independence, MO exploring the records of members of Congress, judges, government officials, and civil rights activists.

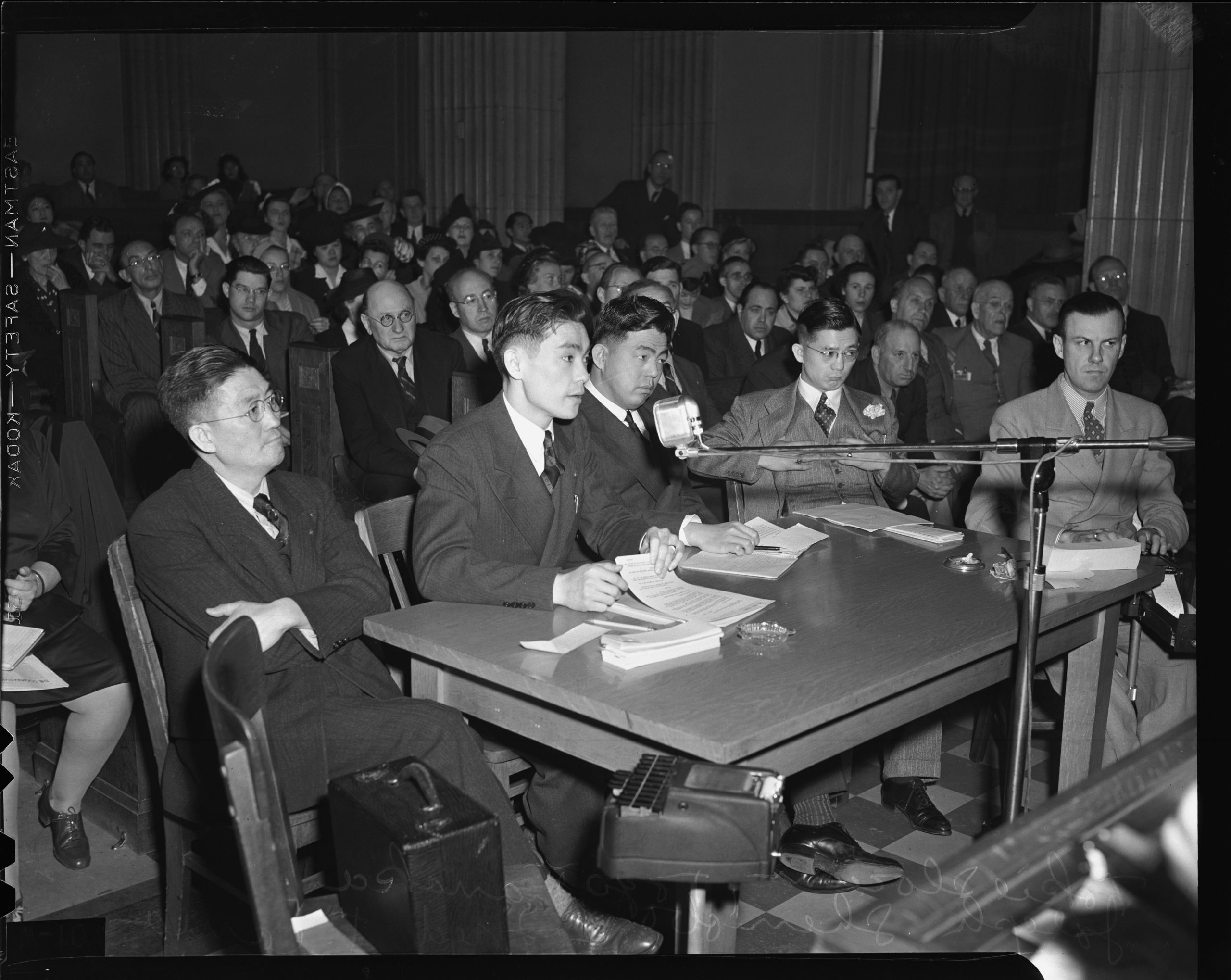

When doing historical research, I always try to evaluate the purpose of a letter or testimony in terms of its potential consequences. For example, the hearings of the Dies Committee (known as the House Un-American Activities Committee) in 1943 on subversive activities in the camps are filled with statements about Japanese Americans that range from the curious to the outlandish (and frankly racist). Although the Dies Committee’s report did not actually find any confirmed acts of espionage among Japanese Americans, Dies (a conservative Democrat) and his Republican allies used the media frenzy around the committee as a means of attacking the Roosevelt Administration, which they alleged was being too “soft” on Japanese Americans.

Interestingly enough, President Franklin Roosevelt’s correspondence contains very few mentions of Japanese Americans or the camps. As historian Greg Robinson points out, Roosevelt’s distanced approach to the incarceration speaks volumes about his lack of interest in protecting a minority during the war, which we can relate to his longstanding prejudices regarding Japanese Americans. Yet First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was concerned about the mistreatment of Japanese Americans. Perhaps my most wonderful find this summer was a letter sent to former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in September 1945 by a government official pleading for better protection for Japanese Americans facing harassment from white terrorists in California. Eleanor Roosevelt then sent the letter on to Governor Earl Warren in hopes that the California state government would offer the returnees more protection from hate crimes. I had known about these letters because Mrs. Roosevelt wrote a similar letter to President Truman, which I found at the Truman Library, but I had not known the extent of her letter writing campaign. Her involvement seems to have made a difference in terms of getting Truman to take an interest in protecting Japanese Americans as well.

While the unjust targeting and profiling of Asian Americans and Asian immigrants in the United States is hardly a contemporary problem, we also know that the COVID-19 pandemic has spurred an increase in Anti-Asian hate crimes. How does our antagonistic and often violent contemporary political climate affect your work and why is it important, now, to surface this legislative and testimonial history related to the Second World War?

While I don’t lose sight of the differences between past events and today’s climate, the present has always been a source of inspiration for my work. Even before the pandemic, the formal renunciation of Korematsu v. U.S. by the Supreme Court in 2018 was an important turning point, even though it was used by the Court to justify the Muslim Travel Ban. The political rhetoric of the COVID-19 pandemic, in its current iteration, has sparked a new wave of anti-Asian hate, but such anti-Asian violence is rooted in a longer history of racism and xenophobia in the United States—and California in particular. Part of why I do my research is to understand why this wave is different from previous cases, and to show how political rhetoric can have immediate consequences for communities targeted by it.

In terms of Congress, the January 6 committee is a great example of how Congress can use hearings to capture the attention of the American public. To give a parallel example from my own research: In 1942 members of the House committee on migration, known as the Tolan Committee, orchestrated a hearing to learn about the rumors being spread against Japanese Americans. Congressman John Tolan of Oakland and his committee went to the West Coast in February 1942 to hear from both government officials and community representatives to see whether there was any substance behind the rumors. Unfortunately, the hearings had the opposite effect; instead of exposing the truth, government witnesses at the hearings, such as then-California Attorney General Earl Warren, further legitimized the rumors and backed a forced removal policy. In their aftermath, the Tolan Committee concluded that there was a palpable sense of fear among West Coast residents, but also included in the official record that there was no proof of Japanese Americans committing acts of sabotage.

This summer, you worked as a Public Fellow with Densho, a nonprofit dedicated to documenting the stories of Japanese Americans who were unjustly incarcerated during World War II. Can you share a little bit about your role at the organization? What was the most exciting or gratifying aspect of your work at Densho?

Densho is a wonderful organization, and having the chance to work with it has been quite an enriching experience. This summer I worked closely with Densho’s Content Director Brian Niiya as an author for the online Densho Encyclopedia and as a contributor to Densho’s blog Catalyst. I authored several new articles for the encyclopedia, including one on the history of local movements to earn compensation for Japanese Americans at the city and state level. In addition to my research and writing projects, I sat in on staff meetings and had the chance to chat with Densho’s new Executive Director Naomi Ostwald Kawamura. For me, working with Densho not only gives me the opportunity to share my research under the auspices of a respected organization, but also help educate people about this chapter in U.S. history that has been often forgotten.

Another great experience was being able to publish several blog posts that discussed important yet unknown Japanese American musicians and poets. Some of the musicians who went through the incarceration later played an important role in popularizing jazz music in Japan, and performed with big-name groups such as Lionel Hampton’s orchestra and Count Basie’s.

What, for you, is the connection between historical study and civil rights advocacy? Why is it important as a history scholar to partner with organizations doing equity work?

Although historians are often seen as working within the confines of academia, their work can have a broad impact on society. Japanese American history, in fact, is a great example because it is marked by stories of academics who used their work to support policy initiatives. In the 1980s, historians like Roger Daniels and researchers like Michi Nishiura Weglyn and Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig worked with members of Congress to correct the historical myth that Japanese Americans were incarcerated because of military necessity. Daniels, Weglyn, and Yoshinaga-Herzig demonstrated that the Army and Justice Department had manipulated and suppressed evidence that revealed that forced removal was actually based on race-based assumptions about Japanese American loyalty rather than any demonstrated risk to security. Their work helped bring abut the passage of redress legislation. (UCSC’s Alice Yang has written an authoritative book on the subject). In 2004, when Fox News commentator Michelle Malkin suggested in a book that the incarceration could serve as a precedent for rounding up Muslim Americans during the War on Terror, scholars Eric Muller and Greg Robinson engaged in a real-time blog debate with Malkin regarding the historical falsehoods of her book.

Although historians are often seen as working within the confines of academia, their work can have a broad impact on society.

In terms of more recent events, Japanese American activists in the organizations Tsuru for Solidarity and Densho protested the imprisonment of immigrants at ICE centers across the country and the policy of family separation, precisely on the grounds that it repeated the same experiences Japanese Americans went through during their incarceration. Meanwhile, scholars like Eric Yamamoto, who have written about the Redress movement of the 1980s, have been active in support of historic reparations for the African American community. While organizations like Densho and JANM work on historical preservation, they likewise use historical education as a tool for equity and social justice.

You also have extensive experience as a journalist, contributing regularly to the Japanese American National Museum’s blog DiscoverNikkei. How does your work as a journalist affect your academic approach to research, writing, and oral history? Why is it important to engage both with academic and non-academic audiences about these topics?

My journalistic work for Discover Nikkei has been a rewarding experience for several reasons, both professionally and personally. First, it has helped me improve as a writer. Because readers come from various different backgrounds, I have learned to adapt my writing habits to be clearer and more concise with my messages. I am still learning, but so far it has taught me a great deal and has motivated me to keep going. It has also given me the chance to collaborate with other writers and adapt to other writing styles

Likewise, being able to write for a wider audience elicits a wide range of responses from readers. It is important (and gratifying) for me to engage with non-academic audiences because these stories carry a personal meaning for many people still living. Because of my articles, I have had the chance to meet people who had further information on the subjects of my articles or were fascinated by something they had learned from my work. What is more, as scholars we badly need to engage readers who are not familiar with this narrative of U.S. history. At a time when conservative groups are trying to erase what they call “critical race theory” from history textbooks, engagement with the public is essential to ensure that they don’t succeed in whitewashing our nation’s history.

Banner Photo: Cover of the Pacific Citizen, March 15, 1952 from the Pacific Citizen digital archives.