Undergraduate Profile: Elina Juvonen

Elina Juvonen is an undergraduate student at UC Santa Cruz double majoring in History and Anthropology. She is currently working as a THI Undergraduate Public Fellow with The Okinawa Memories Initiative (OMI). She is also a 2022-2023 THI Undergraduate Research Fellow. Her project, “Family and Foreign: Investigating Representation and Contradiction in 1950s Women’s Magazines,” was the recipient of the the Bertha N. Melkonian Award. In April, we spoke to Elina about her role at OMI, the importance of public history projects, and the evolution of her research on the construction of American womanhood in 1950’s women’s magazines.

Elina Juvonen is an undergraduate student at UC Santa Cruz double majoring in History and Anthropology. She is currently working as a THI Undergraduate Public Fellow with The Okinawa Memories Initiative (OMI). She is also a 2022-2023 THI Undergraduate Research Fellow. Her project, “Family and Foreign: Investigating Representation and Contradiction in 1950s Women’s Magazines,” was the recipient of the the Bertha N. Melkonian Award. In April, we spoke to Elina about her role at OMI, the importance of public history projects, and the evolution of her research on the construction of American womanhood in 1950’s women’s magazines.

Hi Elina! Thanks for chatting with us about your public fellowship work and your research. To begin, could you tell us a little bit about The Okinawa Memories Initiative and how you first became involved with the organization?

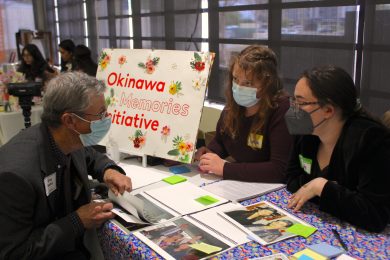

Absolutely! The Okinawa Memories Initiative (or OMI) is a public history research project based here at UCSC that focuses on the postwar history of Okinawa, Japan. The project originally started with a group of photographs taken by an American service member in Okinawa in the immediate aftermath of WWII. Recently, the project has expanded to study the Okinawan diaspora. OMI’s main focus at the moment is a collaboration with the Okinawa Association of America (OAA), a community organization in Southern California. Our undergraduate research team is conducting oral histories, scanning a large archival collection, and creating original exhibits with the OAA.

I was first introduced to the project because I took a class with Dr Alan Christy, the director of OMI, in my freshman year. I was very new to college and history research, but I knew I wanted to gain some kind of practical experience, so I started coming to OMI meetings. I’m so grateful to have found OMI early on in college, because it’s been an enormous part of my UCSC experience and has helped me to understand my own interests and to meet lots of inspiring and dedicated people.

You’re currently serving as a THI Public History Fellow at OMI. In this position, what do you spend the majority of your time doing? What are some skills you have gained or honed during your time with the organization?

My main responsibility is to lead the undergraduate exhibits team in creating a digital exhibit with the OAA’s archival material. We’re very fortunate to have Professor Noriko Aso and PhD candidate Meleia Simon-Reynolds as advisors on the team, who have taught us about exhibit labels and writing, object selection, and community-based research. We spent a lot of time on object selection and research, and now we’re going through several rounds of drafting and feedback before we publish the exhibit in its final form this quarter. One of the most meaningful parts of this position for me has been building relationships with members of the OAA. Collaboration with the OAA leadership, as well as conversations we’ve had with the larger OAA community at their events, has really shaped this exhibit, and I’m excited for them to see the final product. I’m also on the undergraduate leadership team, which involves administrative and collaborative work with the different teams in OMI as well as planning for the second year of our summer internship program, the OMI Scholars program.

In general, working with OMI through different positions has been an invaluable learning experience. In an academic sense, I’ve learned about Okinawan history, the Okinawan diaspora, and the history of US military bases abroad. I’ve learned about putting together exhibits, archival metadata and using oral histories in historical research. My work with OMI has also given me confidence in my leadership and collaboration abilities.

As a history major, how do you see the humanities work you do in the classroom connecting with values or goals of an organization like OMI? Why are public history projects important?

Working in a public history project has shown me over and over again how deeply history matters.

I’ve always been interested in history, but working in a public history project has shown me over and over again how deeply history matters. That’s been especially clear during our work with our community partner, the OAA. Working so closely with community members, we hear how historical events that we learn about in the classroom affected people around the world. When we do research exhibits at the OAA’s events, it’s very moving to see people’s excitement about the fact that OMI exists, and that college students want to learn about their families’ history.

You are also a 2022-2023 THI Undergraduate Research Fellow. Your research project, “Family and Foreign: Investigating Representation and Contradiction in 1950s Women’s Magazines,” received the Bertha N. Melkonian Award. Congratulations! Can you give us a brief synopsis of your project?

Thank you! It is such an honor to receive the Melkonian Award. My project, which was completed as a senior thesis in anthropology, investigates how women’s magazines contributed to depictions of both American and “foreign” identities during the 1950s. My research shows that these depictions and categories often related to ideas about the family, which aligns with the emphasis on the nuclear or “traditional” family ideal that emerged in that period. While doing this research, however, it also became clear that I was writing a paper about women’s magazines as a genre and source. Second wave feminists and feminist scholars, beginning with Betty Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique, argued that women’s magazines were a source of oppression for women in the postwar period, and because of this, the genre has been largely dismissed. I argue that this understanding obscures the complexity of women’s magazines during the 1950s. Women’s magazines were actually highly multivocal, and presented a range of opinions and authors in each issue. I argue that this multivocality creates a unique source for understanding debates about belonging in America in the 1950s.

Your research pushes back against the argument that women’s magazines in the 1950s were oppressive or inconsequential, and instead focuses on the way these magazines constructed an idealized American womanhood in contradistinction to concepts of “foreignness.” I’m curious about the relationship between the “international issues” addressed by such magazines, and the concretizing of whiteness for the American readership. Can you say a little more about this?

Assimilation to mainstream, white American society was tied to achieving a “respectable” family.

That’s a great question! I went into this project thinking that I would find much more consensus on issues in these magazines than I did. Instead, what I found was that magazines – for example, Ladies Home Journal, which was my main focus– presented a wide range of viewpoints to their readership. This led to a lot of contradictions within magazines, sometimes within a single issue. For the most part, magazines presented normative views, idealizing white American families with a housewife and working father. However, magazines sometimes attempted to include groups that didn’t fit into that category, and they did so by relying on the same family ideals. For example, when Black families were presented in magazine features, the family’s self-reliance, religion, and devotion to their children were emphasized– all traits that conformed to the nuclear family ideal. On the other hand, women who became pregnant outside of marriage were redeemed by getting married, even if the marriage was unhappy, or by their more respectable parents taking custody of the child. In other words, assimilation to mainstream, white American society was tied to achieving a “respectable” family. On the other hand, foreignness was often tied to a departure from the family standard. For example, articles on Soviets, which were surprisingly common, criticized the USSR’s reliance on women as workers, often arguing this denied them the opportunity to be good mothers. Rather than creating a wider “enemy” image of Russians, women’s magazines seem to have remained sympathetic to Soviet women, who were depicted attempting to create good family lives for their children, while harshly criticizing the regime for its effect on the family.

This distinction was especially clear in articles that presented immigrants, because both their “foreign” and “American” traits could be depicted in the same article. Those articles say a lot about the acceptable immigrant: out of all of the articles I read, there was only one about a non-white immigrant, and she was a Japanese war bride, married to a white GI.

What is one unexpected discovery you made as you did research for this project?

I had so much fun digging through the Women’s Magazine Archive– there is a treasure trove of interesting articles in old women’s magazines! My favorite part of reading the magazines were the letters to the editor. It’s clear from reading those that many readers felt deeply connected to the magazines. Women would write in to respond to specific articles, but they would also write about their memories of their mothers reading Ladies Home Journal, or that the magazine helped them to make pivotal decisions– whether going to college or opting for a home birth. Reading those letters expanded my understanding of the role of women’s magazines in readers’ lives.

How has the project evolved since your conception of it?

The Women’s Magazine Archive, which is newly available to UCSC students, gave me access to a large range of magazines.

My project and focus has evolved a lot from my first proposal. When I started thinking about this project, I was actually interested in studying idealized womanhood in teen magazines. I expected that women’s magazines from the 1950s would be narrowly focused on domestic life, how to be a good housewife and mother– so it surprised me to see that they also contained political articles and coverage of world events. The Women’s Magazine Archive, which is newly available to UCSC students, gave me access to a large range of magazines. I was also inspired by recent scholarship on women’s magazines that emphasizes their complexity and responsiveness to readers, as well as Irene Lusztig’s film, Yours in Sisterhood, which explores the impact of Ms magazine on its readership.