Alumni Profile: Martin Rizzo-Martinez

Martin Rizzo-Martinez received his PhD in History at UC Santa Cruz in 2016. After completing his degree, Rizzo-Martinez worked as an adjunct professor and then went on to work at the California State Parks. He recently published a book, and generously discussed his writing process.

Martin Rizzo-Martinez received his PhD in History at UC Santa Cruz in 2016. After completing his degree, Rizzo-Martinez worked as an adjunct professor and then went on to work at the California State Parks. He recently published a book, and generously discussed his writing process.

Rizzo-Martinez will be the featured speaker for the 25th Amah Mutsun Speaker Series – Indigenous Santa Cruz. We were happy to catch up with Marty to discuss his life after completing his PhD.

Hi, Martin! Thank you for agreeing to talk with us about life post-PhD!

To begin, could you tell us a bit about what you have been doing since graduating with your PhD from the History Department at UCSC?

After completing my PhD at UC Santa Cruz in 2016, I went into adjuncting at UCSC, Cabrillo, and Salinas Valley State Prison teaching to inmates for a few years. I kept applying to postdocs, and fortunately I received the UC Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellowship to work with Dr. Cliff Trafzer at UC Riverside. My work at UC Riverside allowed me some space to step away from teaching and work on my book and some other projects. I feel very fortunate to have gotten that postdoc; it changed everything! I was able to do all of these edits and transform the dissertation into a book, and finally see it come out.

Following my postdoc, I got a job with California State Parks as the Historian for the Santa Cruz District, so I was able to return to Santa Cruz, this time working in public history with our parks in town. The Santa Cruz District (34-36 parks) includes most of Santa Cruz Mountain Parks, Watsonville, all the way up to the San Mateo coast! There are a mix of job tasks, for sure. Lots of things take us into the parks themselves, such as surveying and training docents and gate staff about cultural history. As a historian, part of what I’m charged to do is take care of historical structures, arrange for repairs, and ensure that the historic cores of certain buildings remain intact. For example, adobes fall into disrepair and we need to rebuild those. Probably the most fun part of the job for me, though, is the cultural history stuff. I’m working now at the Santa Cruz Mission adobe, creating new exhibits with Native partners. I should also note that I am the tribal liaison, where I do tribal consultation with tribal partners. Part of my job is to interface and work with tribal partners on all different kinds of projects. We have really great partnerships with Amah Mutsun right now to steward some of the lands. For example, up in Año Nuevo State Park, the Amah Mutsun, state parks, and an archaeological project at Berkeley have worked together for 15 years doing a lot of great archaeological work. We also work with the youth of the Amah Mutsun tribe who serve as land stewards, so they learn land management techniques like controlled burns, and work to reintroduce native plant species.

This work sounds so interesting! One of your ongoing projects is the rebuilding of Big Basin, which burned down in the CZU Fires. Can you tell us more about that? What do you hope to change with this rebuild?

We’re working with multiple tribal partners to reimagine what Big Basin could look like, which was not something that was done when Big Basin was first built. It’s nice to have an opportunity to rethink things. There is a big debate about whether Big Basin should be reconstructed exactly as it was before it burnt down, replicating buildings from the 1940s and 50s, like its iconic lodge. The more prevailing side of debate wants to take the opportunity to do something different. For example, we need to think about the environmental impact of cars; there should be a shuttle so there aren’t as many cars coming in. We need to also think about the cultural side– what would the tribes we work with like to see there? There are opportunities for things like using parts of the land for tribal gatherings and special use for ceremonies. How can Big Basin be rebuilt to reflect these needs?

A book came out last fall by local historian Tracy Bliss about Big Basin history, and she discovered a bunch of women involved in the preservation of Big Basin who were removed from the official story and the memory markers that were in the park. There’s a push now to not tell the same version of white man’s history of Big Basin. How do we reconstruct Big Basin so these histories are not erased but included as a central part of Big Basin’s history?

In general, people are interested in trying to figure out how we can retell stories in a more inclusive way, which I think is great. After the George Floyd murder and protest, Mission Santa Cruz became a target for protest, which I totally understand why. People were fed up with official colonial histories and that presented an opportunity to make changes to how we present the history of places like the missions. In the American South, that energy was focused on removing Confederate monuments. In California, our version of that is the missions. This Spanish colonial history has been glorified for so long, but it’s a pretty awful history. Fortunately, people are wanting to see change in how we tell stories and remember history.

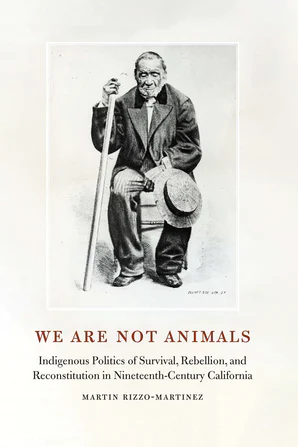

Congratulations on publishing your new book, titled We Are Not Animals: Indigenous Politics of Survival, Rebellion, and Reconstitution in Nineteenth-Century California. Can you tell us more about your book?

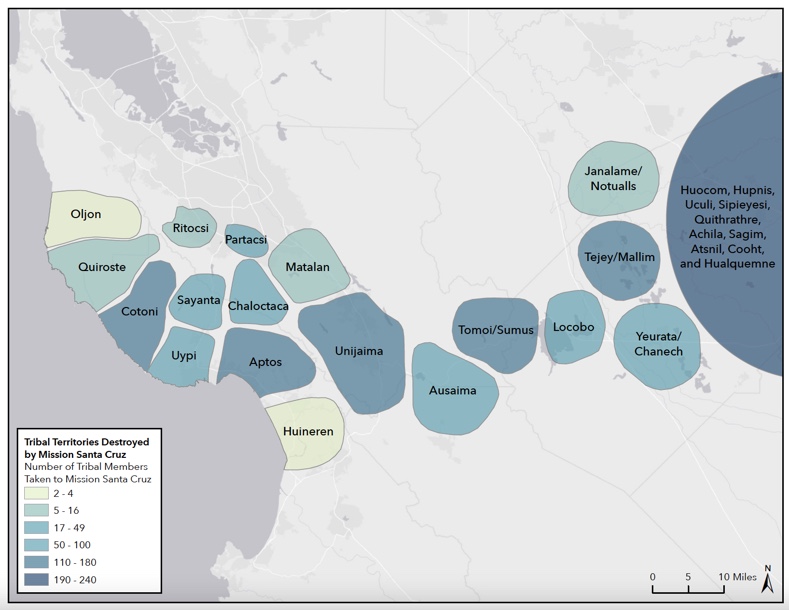

The majority of studies on colonial California are broad demographic studies. When people talk about the missions, it’s been framed historically as a binary: Spanish colonizers and Indians, and in a very broad demographic way. My book goes beyond those binaries to reveal specific stories of individuals and families. I would say the biggest contribution of the work that people have done over the last 3 or 4 decades is putting together all of the mission records; I’m talking about the baptism, confirmation, marriage and burial records. The Franciscan missionaries kept these very detailed records that had a lot of information about families, expanded kinship ties, and village sites. I was able to kind of put all of that data together, and then worked closely with the oral histories and with other written records to trace out, you know, who individuals were, what the very specific stories were. My book follows the stories of Indigenous individuals and families beyond the mission era, through the Mexican period and then, after 1850, the era of American occupation.

The majority of studies on colonial California are broad demographic studies. When people talk about the missions, it’s been framed historically as a binary: Spanish colonizers and Indians, and in a very broad demographic way. My book goes beyond those binaries to reveal specific stories of individuals and families. I would say the biggest contribution of the work that people have done over the last 3 or 4 decades is putting together all of the mission records; I’m talking about the baptism, confirmation, marriage and burial records. The Franciscan missionaries kept these very detailed records that had a lot of information about families, expanded kinship ties, and village sites. I was able to kind of put all of that data together, and then worked closely with the oral histories and with other written records to trace out, you know, who individuals were, what the very specific stories were. My book follows the stories of Indigenous individuals and families beyond the mission era, through the Mexican period and then, after 1850, the era of American occupation.

When I first started doing the work, a lot of the people I talked to like local historians said, “Well, there’s not much there, you know. Native people just kind of died off.” But of course there is a ton there, right? It’s important to understand that the missions were devastating spaces in terms of the number of people who died in them, the disease that went through them. One oral history from the 1870s with Lorenzo Asisara, who lived in the Santa Cruz Mission, highlights the terrible conditions of the Mission Santa Cruz on the one hand. But on the other hand, the interview doesn’t read like they were victims. He emphasizes all these stories of persistence and ways that indigenous people pushed back. I think that’s a really crucial way to understand those stories, and it’s the same with native communities today. Contemporary Native Californians have their own stories of rebellion and persistence, each community, each tribe, each mission has their own examples of this. In the case of Mission Santa Cruz, 90% of the people died during the mission years, so only less than 10% of the people survived and made it past that era. Survival itself was an act of defiance. I mean, it took a lot of ingenuity. It took a lot of working together, collaboration. That’s what my book focuses on.

I think one of the things that sets this book apart, too, is that I really did center it on indigenous perspective. It’s not really about the Spanish or their perspectives at all. And so, of course, the oral histories were crucial to that effort. Luckily I had that postdoc so I could do additional research to really refine this study and clarify some things. I spent a lot of time editing and writing it better, improving my writing, and trying to just get it more readable. I wanted to make this book accessible for anyone. I wanted anyone who wanted to learn more about the missions to read it, and find it readable. So I spent a lot of time making it academic, but also readable to the public, which is a little tricky. As I’m sure you know, academic writing can get really theoretical.

For anyone wanting to buy the book, Friends of Santa Cruz State Parks is carrying it at a huge discount – 40% off the cover price.

That sounds awesome! What would you say were the most rewarding and most challenging aspects of finishing your book?

I think the most laborious part of it was the editing. When I got a hard copy of the book in February, I started reading through it and I had to stop because I kept thinking of things like, Why don’t I write it this way? I need to fix this. I don’t like reading my own writing. I can’t do it uncritically, I can see all the flaws and everything. So I spent a lot of time going over things and adjusting them. Fortunately, the publisher worked with some great editors and peer reviewers who gave me some excellent feedback. That kind of feedback, I think, really did help the book a lot. It probably took me almost 2 years since I submitted the book before it was actually in prints, which was a little shocking to me. I didn’t realize it would take that long, but there were waves and waves of editing and feedback to incorporate.

What would be the most rewarding? That might be a harder thing to pinpoint. I mean it’s incredibly rewarding to just see the final product. I don’t know if I can describe that feeling. This is something that I worked on for my dissertation, so I’ve been working on this for a decade easily, right all through my grad school, and then, having some years after stepping away a little, then coming back to it. I’ve spent so much time in my life working on it, that to actually see it, you know, come to a finish is incredible. I mean, this is probably a really obvious answer, but nothing else compares to it. I mean to actually have that box sent to my house and open it up and be like, “Oh, my gosh! Here it is.” It’s just an incredible feeling.

You have also been teaching at UC Santa Cruz while finishing your book. What have you taught? How has teaching influenced and helped shape your research, and vice versa?

I’ve been teaching mostly core classes at UC Santa Cruz. I’ve taught Rachel Carson core and, some years back, I taught Oakes’ core, and I was teaching Stevenson last quarter. The Carson Core in particular, gets into a lot of environmental studies and they do a focus on indigenous land management. That’s been a nice fit. I like teaching there because it’s the work that I’m doing with parks in collaboration with the tribes, so I’m able to bring in stuff that I’m working on about local history and local tribe issues.

Maybe the best example I can give is a sideways example. I also started co-producing a podcast called Challenging Colonialism over the last year in an effort to find other ways to teach things. I’m interested in how you can teach things beyond academia. I could write an academic book, and like I was saying earlier, I try to write books so that anyone could read them. I do think it’s really important to get information and knowledge outside of the Academy to people in general. That’s why it’s important to be doing public history work. I’m always trying to figure out how we can get cutting edge scholarship or new ways of thinking out to a broader audience who may not be interested in reading a book or taking university classes. So I put together this podcast partly because of that and partly because I’ve really been fortunate to meet a lot of fantastic indigenous scholars and activists and people doing all sorts of great work, and it occurred to me that I should be recording these conversations. The podcast, Challenging Colonialism, augments native voices on different topics. We just released an episode on the boarding schools, where I interviewed some alumni from the Sherman Indian School. We’re working on one now that explores the history of anthropology in California, and how the relationship between anthropology and native people has changed over the years and went from a really extractive, destructive project to a more collaborative endeavor.

You seem to have a lot of engagement with public history, appearing for book talks at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History and for Amah Mutsun Speaker Series (hosted by the American Indian Resource Center). How do you envision the role of public history in your broader research and historical work?

I don’t want to take anything away from the academic world, because I think academia and academic studies are really important. But we all know that there is a limited audience to that, right? You’re not going to get people to read heavily academic studies, even if it’s fantastic and groundbreaking, and really changes things. Since being in academia I’ve felt that things are written sometimes just for academics. However, you can also take things that are really complex and you can put them in simple ways that are just straightforward. If an idea is a good one, you ought to be able to break it down into a really simplified way for people to understand it. I think that’s what we do in the exhibits at state parks. There are certain mandates. You have to make it so that anyone of any age could read it, right?

I don’t want to take anything away from the academic world, because I think academia and academic studies are really important. But we all know that there is a limited audience to that, right? You’re not going to get people to read heavily academic studies, even if it’s fantastic and groundbreaking, and really changes things. Since being in academia I’ve felt that things are written sometimes just for academics. However, you can also take things that are really complex and you can put them in simple ways that are just straightforward. If an idea is a good one, you ought to be able to break it down into a really simplified way for people to understand it. I think that’s what we do in the exhibits at state parks. There are certain mandates. You have to make it so that anyone of any age could read it, right?

And so that’s where I think public history is really important in that way. We’re always reinterpreting the past I think in really important ways. Take, for example, the mission. The history of the missions that’s been taught in schools was put together 100 years ago, by Franciscan scholars who were trying to celebrate the missions and the missionaries. And so the story that got handed down by Franciscan scholars was done to support construction of Highway 101 (which links the cities that once had missions) and the restoration of these missions. But it was a false history, right? It was a really devastating false history. And for native people, those histories are really insulting. They ignore thousands of years of Indigenous culture and society. The accepted history of California is built around assumptions about native people being inferior. They’re built on racism. So if you only learn what you do about history from public markers, you’re gonna have a very narrow view of things that’s really built on racist assumptions, and that’s where I think it’s so important to bring more inclusive histories from the last 40-50 years of academic research to the public, so that so that anyone can also learn those.

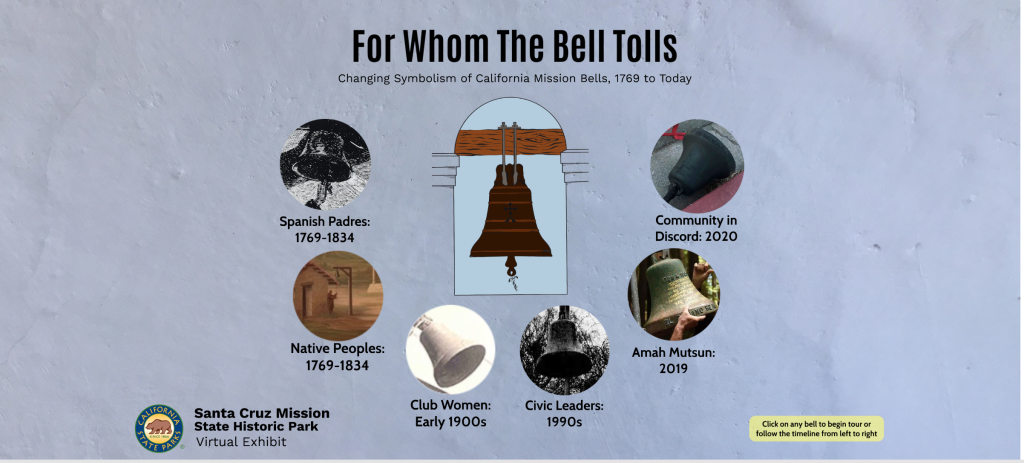

One of the things that was cool that you’re reminding me of as we’re talking is that the City of Santa Cruz responded in a really positive way to BLM protests and asked how they could work with our tribal partners to do a better job with this fraught history of the missions. The City reached out to tribal partners and to state parks to see how we could tell these often obscured stories in our parks and in the city. Santa Cruz agreed to the Amah Mutsun’s request to remove the bell marker from the tower off Ocean Street. These bells were built in the early 1900s by Franciscans to celebrate the missions, but for Native people these bells were sonic signifiers of colonialism. They were there to bring people into the missions and entice them, but they were also there to exert a sphere of control. The bells rang the first thing in the morning to wake people up. They rang to tell them to get to work, to stop working, to go eat. They would get in trouble for not responding to the bell. They dictated native people’s lives. The bell was very much a signifier of Spanish colonialism.

There was a big ceremony to remove the bell marker, and to me it’s an example of how this type of public history can have meaningful significance for communities. When the bell was removed last August I saw a lot of representatives from Santa Cruz who were there, but there were also native California people from all up and down the State from San Diego to Los Angeles to Oakland. There were a ton of people who came here, and it was very powerful, emotionally. There were so many emotions going, and there was a moment where people really felt like, “Hey, this is a good step in the right direction.” These opportunities to address historical wrongs in a public way have an important healing value for native Californians. And these things are emblematic of wounds, family wounds, transgenerational traumas. And so when you address these things in a big way like this, it does offer an opportunity for healing.