Faculty Profile: Shelly Chan

Shelly Chan is an Associate Professor of History at UC Santa Cruz and History alumna. This year she is a 2025-26 Faculty Fellow at The Humanities Institute. Her current project, “Disappearance of the Nanyang: A Forgotten History of a Diasporic Region,” examines a diasporic region between China and Southeast Asia known as the “Nanyang” or the “South Seas” and its impact on the global restructuring of Asia. We recently caught up with Professor Chan about her research and her experience transitioning from archival research and fieldwork to writing.

Hi Professor Chan! Thanks for chatting with us about your 2025-2026 THI Faculty Research Fellowship. To start off, could you please tell us a little about yourself and your research interests?

Sure. I am a historian of modern China with a focus on migration and diaspora. Because of my deep interest in people and things in motion, my work is necessarily transnational, long historical, and intercultural. I am drawn to the study of interfaces, contact zones, and borderlands, and the complex experiences and materialities that emerge as a result.

I am from Vancouver B.C. and Hong Kong. I have been an immigrant almost my entire life, though I have not always thought of my personal, familial, and intellectual journeys as intertwined. As I get older and start to look back, I have been able to see and embrace that more. You also asked at the right time.

You also led the Transnational China Research Hub in 2022-2023 at The Humanities Institute. Could you share more about this research project, the events and collaborations it fostered, and the significance of approaching China from a transnational lens?

The research project that I co-led with Ben Read (Politics) and Yiman Wang (Film and Digital Media) tried to rethink China studies collectively from a juncture of multiple crises and shifts. The pandemic, increasing US-China tensions, surge of anti-Asian racism and violence, and conflicts within China and on its margins were changing base assumptions and revealing new and old divides. At that time, most of the scholarly conversations had been about how to keep doing China studies in practical terms, given various challenges with travel and research, but less to do with the shifting concerns and structures of feeling. When a campus-wide call for seed grants was announced, I also happened to have freshly arrived at UCSC and was looking to connect with like-minded faculty and student colleagues. With much support from THI, our team organized a speaker series, a reading group, and an international conference that gathered scholars from very different disciplines and a sizable audience online. We discussed the urgency of renewing attention not only to China as a country but also to the many different “Chinas” that have taken shape historically and globally, whether accepted or resisted. Transnational was certainly not a new concept, but it felt appropriate to reach for other configurations at a time of retreat and reflection. Our conference was one of the largest public conversations that tried to meet the moment in some way.

This framework also animates “Disappearance of the Nanyang: A Forgotten History of a Diasporic Region,” the project you’re working on for your THI Fellowship. Can you share more about the project? What initially drew you to it?

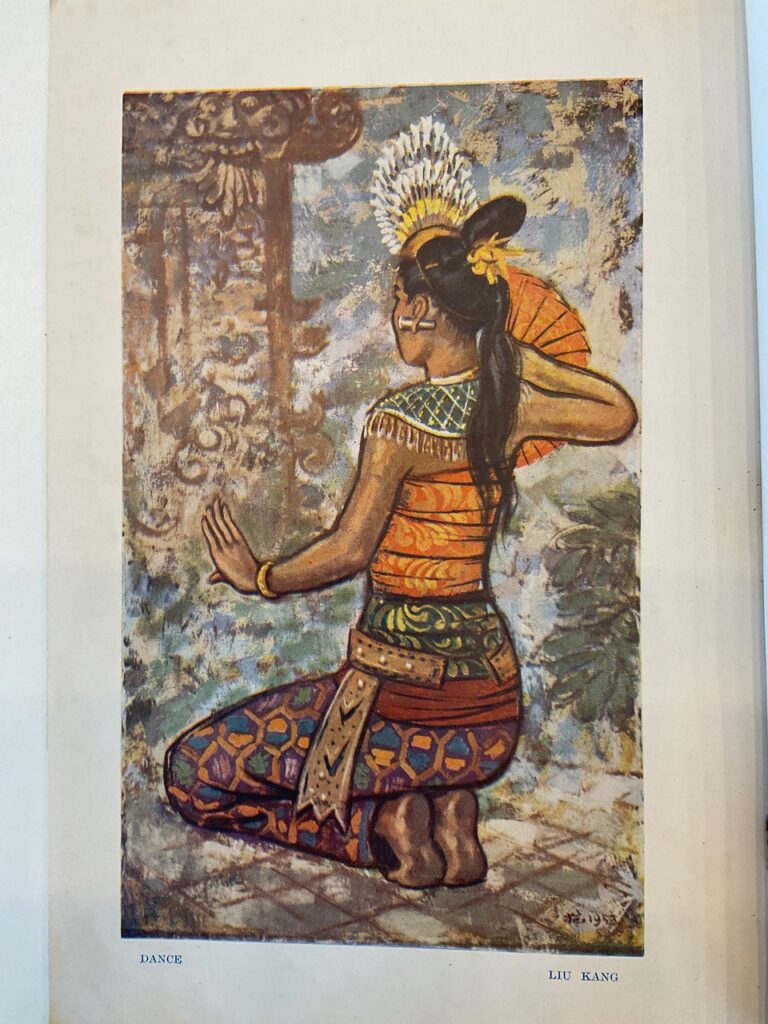

I am writing a book about how a diasporic region between China and Southeast Asia unraveled during the 1950s-60s, using its closure to explore the radical restructuring of Asia. Some of the most well-known facts about this transition were related to decolonization, nation-building, and the Cold War, but the story is not often told from the perspective of diasporic Chinese traders, laborers, and artists. What first drew me to this research is discovering how frequently the name “Nanyang” or “South Seas” appeared in the print and visual sources and built environments of the early twentieth century – as a geography, an identity, and a symbol of modernity associated with the Chinese diaspora – and then how quickly it was abandoned by the late 1960s. As national frontiers closed and the international economy was remade, the old patterns of migration and circulation also drastically changed. In other words, my project seeks to explain the disappearance of the Nanyang region and identity to get at the broad impact of regional and global restructuring.

Some of our readers might not be familiar with the Nanyang (南洋) region. What is the significance of understanding and centering the history of the Nanyang and how does your scholarship seek to intervene in existing conceptions of the region, as well as China?

The Nanyang literally means “South Seas” in Chinese and is counterpart to “Gold Mountains” (gum saan), another popular geography of Chinese migration and diaspora. Because many scholars find the name “China-centric” in the contemporary context, they tend to say that the Nanyang is the same as today’s “Southeast Asia.” It is not. Not only that, but the switch also erases the conflicts and violence accompanying the rise of Southeast Asia as a region of new states and Cold War struggles. Centering the Nanyang as a diasporic region, I think, helps address the erasures rooted in the transformations of the 1950s-60s and disrupts the sense of an equivalence with “Southeast Asia” or “China-centrism.” Instead of an area of would-be nation-states, the Nanyang was a maritime crossroads, a frontier of production, and a geography of diaspora, resulting in an overwhelming dominance of Chinese settlements. Despite their broad participation in decolonization, Nanyang Chinese were deemed backward and threatening to the interests of nation-builders and cold warriors in both China and Southeast Asia. This politically charged “Chinese problem” was a key question of the 1950s-60s world that has largely been forgotten. But it also gives us an opportunity to foreground a diasporic zone like in the study of borderlands to challenge the rigidity of area studies and nationalist histories.

You last conducted archival and field research overseas for the project in the summer of 2024. What archives did you visit and where? Can you tell us about your experience? Was there a specific moment in your research that particularly stands out to you?

I went to many places and was trying to finish my research that had gone on for a few years. Because one of the book chapters is about a group of diasporic Chinese artists known as “Nanyang painters,” I started in Singapore, doing research at the National Art Gallery and the National Library, before heading to Indonesia to meet local researchers and visit different museums in Jakarta, Surabaya, and Bali. My final stop was Hong Kong, where I spent time at the University of Hong Kong library’s Special Collections, Asia Art Archives, M+ archives, and the Public Record Office. It was a fruitful summer. Particularly standing out is how the signs of the Nanyang as a lost region were in fact everywhere – in the print and visual records, on the streets, in local conversations, and in everyday life. And I am only referring to the places I had the time to visit!

What is your process for transitioning from fieldwork and archival research into writing? Do you have any advice for graduate students or early-career researchers navigating that stage of their projects?

Transitioning from research into writing is a real struggle! The only thing to do is to trust the process and not be afraid of the mess you make. Recently, because I have been writing about painters and would like to learn more about painting, I was watching a British TV show where winners of a contest show their process from start to finish. The show features many different types of medium and subject matter, as well as styles and techniques. What inspires me the most is how all beginnings are rather messy and can be very far off target. Witnessing that I feel intrigued, amused, and sometimes a little nervous for the painter. But then I also watch how calmly the painters talk themselves through the mess, and how they break down a drawing into pieces and steps. Slowly a picture emerges. Even when they can’t get it quite right has inspired me too. It made me realize that the painter’s process is like ours. It takes free writing, broad contours, fine detail, good measurements, loads of positive self-talk, and finally letting go.

Lastly, it’s really special that you’re a UC Santa Cruz History alumna who is now an Associate Professor in the department. How has your experience—studying here, teaching at other universities, and then returning to this program—informed the way you approach your research, teaching, or mentorship? And how do you reflect on your academic journey and what it means to return to the place where it began?

Thank you for asking about that. Yes, it’s been special personally. I would attribute much of my student experience to the open, interdisciplinary environment in History, the Center for Cultural studies headed then by Jim Clifford and my advisor Gail Hershatter, and a grad student group called APARC (Asia-Pacific-Americas Research Cluster). Faculty did a lot for us, but we also shared a sense of vision and independence. Once I became a faculty member, I noticed how my training allowed me to engage meaningfully with others. Also, because I was fortunate to be at a larger institution where intellectual range and mentorship were highly valued, I continued to hone my skills and attention. The lesson I learned is that no researcher can exist alone, but it is also important to trust oneself and trust the process. Now back at UCSC, I try to practice and support that discovery, even if it sounds ordinary enough.

Banner image: Singapore National Gallery. Photograph by Matt Briney. All other photographs taken by Shelly Chan.