Grad Profile: Bree Booth

Bree Booth is a PhD Student in the Latin American and Latino Studies Department. Bree’s project, “Tracing Queerness Through the Atlantic,” approaches “historical archives as both source and object.” As Bree explains, archival documents shed light on the non-normative intimate lives of enslaved people, and the archive as a politicized institution influences how we read stories about queer black historical subjects.

Bree Booth is a PhD Student in the Latin American and Latino Studies Department. Bree’s project, “Tracing Queerness Through the Atlantic,” approaches “historical archives as both source and object.” As Bree explains, archival documents shed light on the non-normative intimate lives of enslaved people, and the archive as a politicized institution influences how we read stories about queer black historical subjects.

This March we reached out to Bree to learn more about their ongoing research. Bree was a 2021-22 UCSC SSRC-Dissertation Proposal Development Fellow. We talked about their exploratory research, archival discoveries, and how the UCSC SSRC-DPD Fellowship shaped their research project.

Good morning, Bree! Thank you for agreeing to sit down with us and talk about your work. To start us off, can you provide a synopsis of your current research?

Thank you so much for the opportunity to talk more about my project! More broadly my research is concerned with historical archives and transatlantic slavery, with queer theory as a guiding framework. I explore historical archives as both a source and object. As it relates to archive as source, I read/look for documents related to enslaved people and the non-normative (re: queer) relationships they formed in Spain and its former colonies. I’m interested in what we learn about the more intimate or close encounters enslaved people had with each other and others. With archive as object, I consider how the structure or logic of the archive informs the way we read, relay, and perhaps remember certain histories, especially those that are black and queer. In essence, my research seeks to tell a story about historical archives and black queer pasts through ethnographic engagement with the archive and close reading of its contents.

That is very interesting! Quantitative analysis plays a big role in the study of slavery in the Atlantic world. This apprach helps us get an idea of the sheer magnitude and complexity of the slave trade system. The Slave Voyages database, for example, that PhD students, postdocs, and professors at our campus have worked on, approximates the shocking number of slaves traficked across multiple routes spaning the entire Atlantic world. How does your research complement and enrich this important quantitative research?

This is a great question! The importance of the Slave Voyages database can’t be understated. I’ve used it a lot in my preliminary research and also in courses where I was a Teaching Assistant or a Reader. Identity markers such as sex, age, and point of origin that historians have compiled into databases are critical because those statistics give a general idea about who the enslaved person may have been. The qualitative work that I do, I think, enriches this quantitative research by paying attention to documents that perhaps divulge more specific details. Basically I hone in on the particularities of gender and sexual subjectivity. For example, some questions I may consider are: what was the role of testimonios during the Spanish Inquisition? How were testimonios used to reify Spanish laws and morality around topics such as sexuality or sexual orientation and gender roles? In that sense, it’s a beautiful complement to the vast body of quantitative research done because we continue to move closer to knowing as much as we can about people whose material conditions and intimate lives are often purposely forgotten.

A substantial portion of your research is archival in nature. Can you tell us about a historical document or collection of documents that has really excited you as you continue to research queerness and resistive gender roles amongst enslaved people? What is so illustrative or exciting about these archival documents?

Oooh. Yes actually, the document I read during my Fellowship period! Dr. Jeff Erbig helped me create a solid plan for approaching the Archivo General de Indias in Spain. This included using the Spanish national archives website PARES. This website is basically a repository of all the documents found across Spain’s national archives. This is where my initial research began as I started searching for terms such as “esclavo/a” (slave), “pecado nefando” (nefarious sin), and “sodomia” (sodomy). It’s a tedious yet invigorating process, especially when you finally come across something. Which I did!

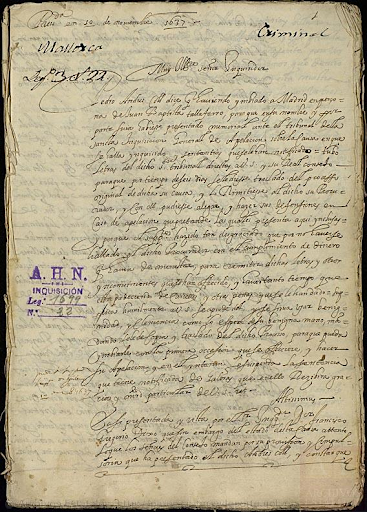

The document is titled “Proceso de fe de Pedro Andrés Coll” (1699). This criminal case record comes from a collection of Spanish Inquisition documents from the colony of Mallorca housed at the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid. The document is over 100 pages of people testifying to seeing Pedro Andres, a Spanish boy, engaging in sodomy (what was deemed “pecado nefando,” or nefarious sin) with an enslaved man, Antonio Jose. What’s interesting about reading this document is how small details are revealed in these larger legal proceedings. For example, I was, I think, 30 pages in when I finally learned how old Antonio was. There have been little details about him because Pedro was the person on trial. There are key details repeated over testimonies of soldiers, local community members, and state officials (namely Antonio’s owner Pedro Sunyer, a member of the holy office). These details include where the encounter took place – “una garita de una muralla,” or sentry tower. People were testifying to the court that they saw Pedro and Antonio with their pants down and one bent over. Some describe yelling at them to stop and others “negro!,” after which Antonio quickly pulled up his pants to run.

While there are some very nuanced and valid questions/implications about power, authority, and consent in the instance of Pedro and Antonio given the age and status difference, what excites me about these documents is the story itself. The fact that there were people watching what was deemed sexual deviance, testifying about it to the court, and villifying the people invovled in the situation, because if they didn’t they could be considered a sinner too. What it also illustrates is just how intricate the archiving of legal proceedings are, especially during the period of the transatlantic slave trade. I would argue they were concerned with matters of the state and the church and the ability of both institutions to solidify a moral code that privileged heterosexual relationships between males and females.

I imagine that given the particular power dynamics at play that structure the historical archive we have about the experiences of enslaved people, it may be difficult to locate queerness, homosexuality, and gender-transgressive behaviors in the historical record of enslaved peoples’ lives. Is that the case? If so, what approaches have you used to find this obscured historical experience in documents that do not explicitly talk about it?

And we should continue to vigorously read for intimate histories, especially histories that speak to desire and closeness in the lives of black (queer) people.

Absolutely! As I described a little bit before, my research project definitely seeks to tackle this question of the role of historical archives in relaying certain histories, especially those that are black and queer. When I look for documents, I look for language that I probably wouldn’t use myself but is more contextually accurate to my historical period of interest. Terms such as “sodomia/its” or sodomy and sodomites, “homosexualidad”, “pecado nefando” or nefarious sin, “demonios” or demons, and many other words. If I’m using the document about Pedro and Antonio as an example, I read against the grain in the sense that I’m looking for the details related to Antonio. The court proceedings are for Pedro (and to my knowledge, I don’t know if Antonio had a separate case), but this is part of where my interest lies in telling a story about Antonio through Pedro and the many witnesses that saw them.

I am very aware of the limitations of researching sexual and gendered histories in historical archives, but I think what my research process illuminated to me this Summer is that it’s not necessarily hard to find documents, it’s just frustrating consistently realizing some things just aren’t there. On the flip side though, there are many things that are there. And we should continue to vigorously read for intimate histories, especially histories that speak to desire and closeness in the lives of black (queer) people.

The UCSC SSRC-DPD program has many intersecting elements, including funds for exploratory research, mentorship from other scholars, and collaborative workshops with other graduate students. What aspects of this program would you say have been most effective in shaping your dissertation project, and why?

The research proposal I used to apply to the UCSC SSRC-DPD Program dramatically changed…in the best ways possible because I walked away from the summer with a lot of clarity on my dissertation project.

I have to say, all of the elements worked really well in tandem for me. The research proposal I used to apply to the UCSC SSRC-DPD Program dramatically changed by the end of the summer. And dramatically in the best ways possible because I walked away from the summer with a lot of clarity on my dissertation project. That clarity came from conversations with my workshop partner, Lexx, who has had more experience doing archival research than me. When Lexx and I read each other’s workbooks, we were able to talk through the distracting thoughts that sometimes keep people from writing and reading. I was also able to gain more confidence in approaching the archive – that is, not being scared of what I might not find and not being scared of the “grandiosity” of the archive. I say grandiosity because oftentimes archives are seen as the holder of history and that’s pretty damn grand! But the confidence to approach my research was instilled through hearing other students talk about their summer research processes, and also through conversations with Dr. Debbie Gould, Dr. Grace Peña Delgado, and Dr. Cecilia Rivas.

The talking, re-writing, and constant clarifying is an invaluable part of the process. Sometimes I think as students and scholars we fear re-writing and deleting huge chunks of words because we don’t want to have to do that intellectual work again. I really took the chance to lean into that fear through my time participating in the UCSC SSRC-DPD fellowship. Stepping into that fear allowed me to create a stronger dissertation/research proposal for future grants and fellowships and also helped me define my two fields for my qualifying exams.