Grad Profile: David Duncan

David Duncan is a fourth-year PhD student in the History Department. Duncan studies twentieth century school desegregation movements in the Bay Area. Duncan has worked extensively in the field of oral history, and has utilized this methodology in his yearlong 2021-22 THI Public Fellowship with Sausalito Marin City School District. Duncan’s project fuses academic inquiry with public engagement and policy discussion. As Duncan explains, “oral history is at its best when it centers public benefit over academic contribution.”

David Duncan is a fourth-year PhD student in the History Department. Duncan studies twentieth century school desegregation movements in the Bay Area. Duncan has worked extensively in the field of oral history, and has utilized this methodology in his yearlong 2021-22 THI Public Fellowship with Sausalito Marin City School District. Duncan’s project fuses academic inquiry with public engagement and policy discussion. As Duncan explains, “oral history is at its best when it centers public benefit over academic contribution.”

In April, we sat down with Duncan to hear more about his work as a Public Fellow. We discussed the long history of desegregation in Marin County, the power of oral history, and the often surprising way people construct historical memory of place.

Good afternoon, David, and thank you for agreeing to speak with us about your ongoing work as a THI Year-Long Public Fellow! To start off, could you give us a synopsis of the work you are doing with Sausalito Marin City School District?

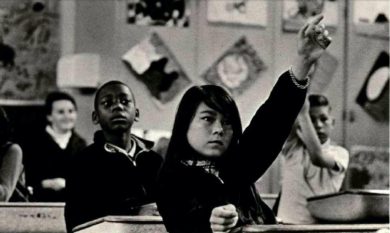

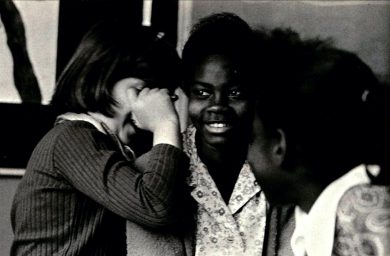

My pleasure, thank you for reaching out! The project with SMCSD stems from my Masters and Dissertation research. Sausalito and Marin City are located on the Northern side of the Golden Gate Bridge in Marin County. Sausalito is a highly affluent city along the San Francisco Bay, and Marin City is a much more diverse and lower income unincorporated area that was built for shipyard workers during World War II. In 1965, the district known as just the Sausalito School District, became one of the first school districts in the United States to desegregate without a court order. The district designed a plan that bussed Kindergarten through 6th grade African-American students from Marin City to mostly white schools in Sausalito. In 1968, a photo essay book was published by the district that included images and student testimony about their experience during desegregation.

Fast forward to 2019, I’m spending a few weeks in Sausalito conducting oral history interviews with previous students, parents, faculty, and administrators from 1965, and SMCSD received the first court order in over 50 years in the state of California to desegregate their schools, again. Then Attorney General Kamala Harris started the investigation, and the order was initiated by her predecessor Xavier Beccerra. In 2019, SMCSD existed on one campus in Marin City for grades K-8, and a charter school in Sausalito operated a separate campus. The new court order resulted in the closing of the charter school, and the district occupying both campuses.

My relationship with SMCSD started in late 2019 when Superintendent Dr. Itoco Garcia asked me to join the Desegregation Advisory Group as an expert advisor. My main task was to present to the DAG and the public about the little known history of the 1965 desegregation effort and advise on the current process.

I was awarded the THI Public Fellows Grant in 2021, with the intent to create a new photo essay book for the new desegregation effort taking place that same year. Dr. Garcia and I planned to republish the 1968 book, have me visit the campus during desegregation to take pictures, implement a website for students and faculty to submit their own oral history experiences of desegregation, create a digital archive for the district, and publish a new photo essay book with the pictures I collected.

That sounds like fascinating work! I’m sure it is very difficult to choose, but is there a specific interview or set of interviews that you conducted that sticks out in your memory for some reason or another? What surprised you or impacted you about this particular interview/group of interviews?

So in this project I am designing a website for the SMCSD community to submit their own oral histories. With students of varying age, parental permissions, the sensitivity of the subject, and the sheer amount of people I hope to include, I thought this approach would cast a wider net and be able to include more people. I did get a chance to sit down with Dr. Garcia in what was supposed to be an interview more focused on the struggles around COVID. It turned into a three hour interview that was much more biographical. I think the only question I asked was “Tell me a little about how you came to be Superintendent at SMCSD.” Dr. Garcia started with his early childhood experiences growing up in Marin City. It’s probably one of my favorite interviews that I have ever done. Dr. Garcia took it in a completely different direction by sharing his entire life and the key moments that led him to where he is today. I love when interviews take unexpected turns and the narrator (interviewee) takes the lead, letting me sit back and listen.

In my Master’s and dissertation research I have been compiling snippets from different interviews into what is called an Oral History Chorus. It has been a useful tool in conference presentations and also for the public in understanding the complexities around desegregation information. This chorus is from students, parents, faculty, and staff who experienced the first desegregation effort in 1965-1970.

With your current work in the North Bay and your involvement in other projects like The Empty Year: An Oral History of the Pandemic(s) of 2020 at UC Santa Cruz, you have a lot of experience working with oral history. Why do you think oral history is such a compelling methodology and practice? How do you understand the relationship between oral history and the more traditional historical method of archival and document-based research in the production of historical knowledge?

That’s a great question and one that I am continually trying to answer and explain. I operate under the definition that oral history is the collection and co-creation of new historical records, with the questions I create and the memory of the narrator forming new accounts. Oral history to many is still considered an outlier to the sort of “mainstream” history of archives and documents that you mentioned. From my understanding the field has been gaining a much wider acceptance in academia in the past 10 years or so, especially with more high profile oral history projects with The Holocaust, 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, and now COVID. Although, at least to me, it doesn’t matter as much what other academics think of oral history because oral history is at its best when it centers public benefit over academic contribution.

“…oral history adds a richness and deeply emotional component that other primary sources like a newspaper or letter don’t convey.”

I was drawn to oral history in the ways that it mirrors the interactions and connections I made with patients when I worked as an EMT from 2010-2018. Quickly being able to connect with strangers, hear their life story, and asking questions that untangle threads of memory is addicting and fascinating to me. I remember speaking to a professor my first year here at UCSC and I asked how I should incorporate oral history interviews into my academic work. They responded that I should simply use the interview material like any other primary source. While I still think that’s true, oral history adds a richness and deeply emotional component that other primary sources like a newspaper or letter don’t convey.

However, memory is a tricky source material to deal with. The inaccuracies that come with memory often aren’t a big deal in most of the work I do. An incorrect date or misremembered name can often be corroborated with other interviews or sources. The important information in an oral history comes from the emotion of recounting particular experiences and how that informs our historical understanding. For example, a major motivation for me to research the history of school desegregation is that most historical works did not focus on the students and teachers who were experiencing desegregation. They often covered the politics, policies, and movements that led to desegregation, but I wanted to know what it was like to live through it. I love a good hunt through an archive like most historians, but I really feel like I am in my element when I’m sitting down in a stranger’s home asking questions and hearing about their life.

There has been some notable public engagement with Sausalito Marin City School District’s history of school desegregation. For example, the popular San Francisco-based Spotify podcast Fifth and Mission featured you on a recent episode “Is School Desegregation in Sausalito Marin City Working?” How do you think your work has inspired or shifted local conversations about school desegregation in the Bay Area?

I don’t think I can take too much credit for shifting the local conversations but I will say that I’ve made efforts to bring more attention to the subject. I think that the history of school desegregation in the Bay Area could be best described as unresolved and unspoken. Networking is a huge part of oral history work and I ask each person I meet to suggest other people I can contact. I’ve been surprised by how eager people are to discuss this subject. Almost as if they have been waiting to talk about it or that it is still an ongoing issue, which in many ways it still is.

The desegregation order in 2019 in Sausalito brought the conversation to the forefront as well and I was fortunate in the way that it created dialogue in the community about the history of what had happened in 1965. I hope that my work continues to bring attention to the past and current issues and I appreciate the local media attention from Fifth and Mission as well as local historical organizations and libraries that have supported my work, including THI.

For many people, the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1960s and 70s evokes a very particular historical memory. Many people think about the Summer of Love, Janis Joplin, and the saga of Patty Hearst. How does the history you are documenting about school desegregation complicate this popularized version of Bay Area history?

A common response I get when I explain my research is that they were not aware of any school desegregation efforts in the San Francisco Bay Area. Even this history that you mentioned isn’t really taught in schools local to the region, or at least for where I grew up in the East Bay. In my EMT days I worked in Santa Clara, Contra Costa, and Alameda County. Driving around all these places I would often daydream and wonder how these places came to be and what their history was. Maybe I’m biased because I’ve spent almost my entire life in the Bay Area, but I’m driven by the fact that the history of this extremely influential and important region for the United States hasn’t received much historical examination. It is my hope that my work starts to include a more complete picture of the history of this time period and reflects the local struggles, activism, and organizing that occurred around school desegregation.