Graduate Profile: Arlo Fosburg

Arlo Fosburg is a seventh-year Ph.D. candidate in the Feminist Studies department, with a designated emphasis in Critical Race and Ethnic Studies, and was a 2025–26 THI Summer Dissertation Fellow. They also represented UC Santa Cruz as one of two UC Network Fellows, selected for submitting a top-ranked proposal to The Humanities Institute. Arlo’s dissertation, “University Discipline: Scientific Agriculture, Militarism, and the Land-Grant College System,” challenges commonsense narratives of the university as an a priori good through a historical analysis of the land-grant college system—showing how efforts to broaden access to higher education for poor white farmers precipitated the mass dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their lands. Over the summer, Arlo conducted secondary site visits and archival research at five different universities. We recently caught up with them about their time in the field.

Hi Arlo! Thanks so much for chatting with us. To begin, could you give us a general synopsis of your research project?

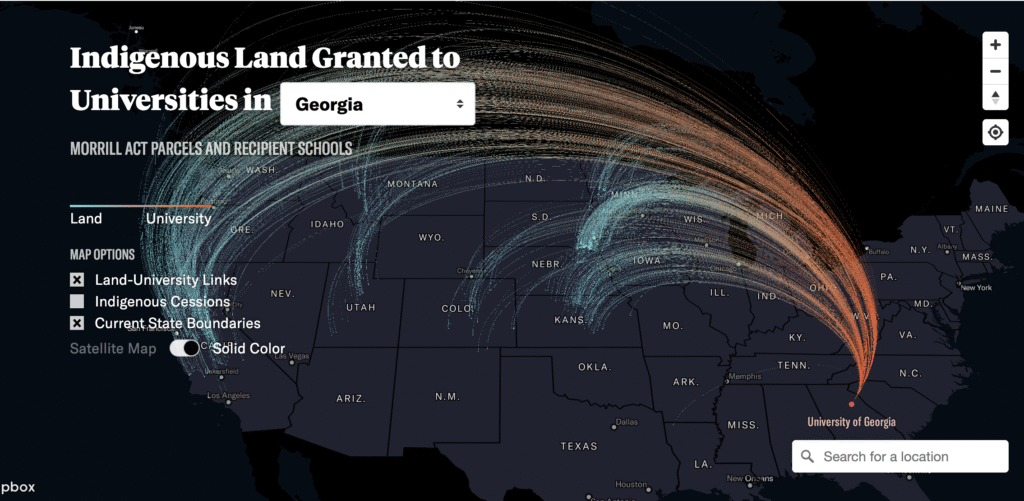

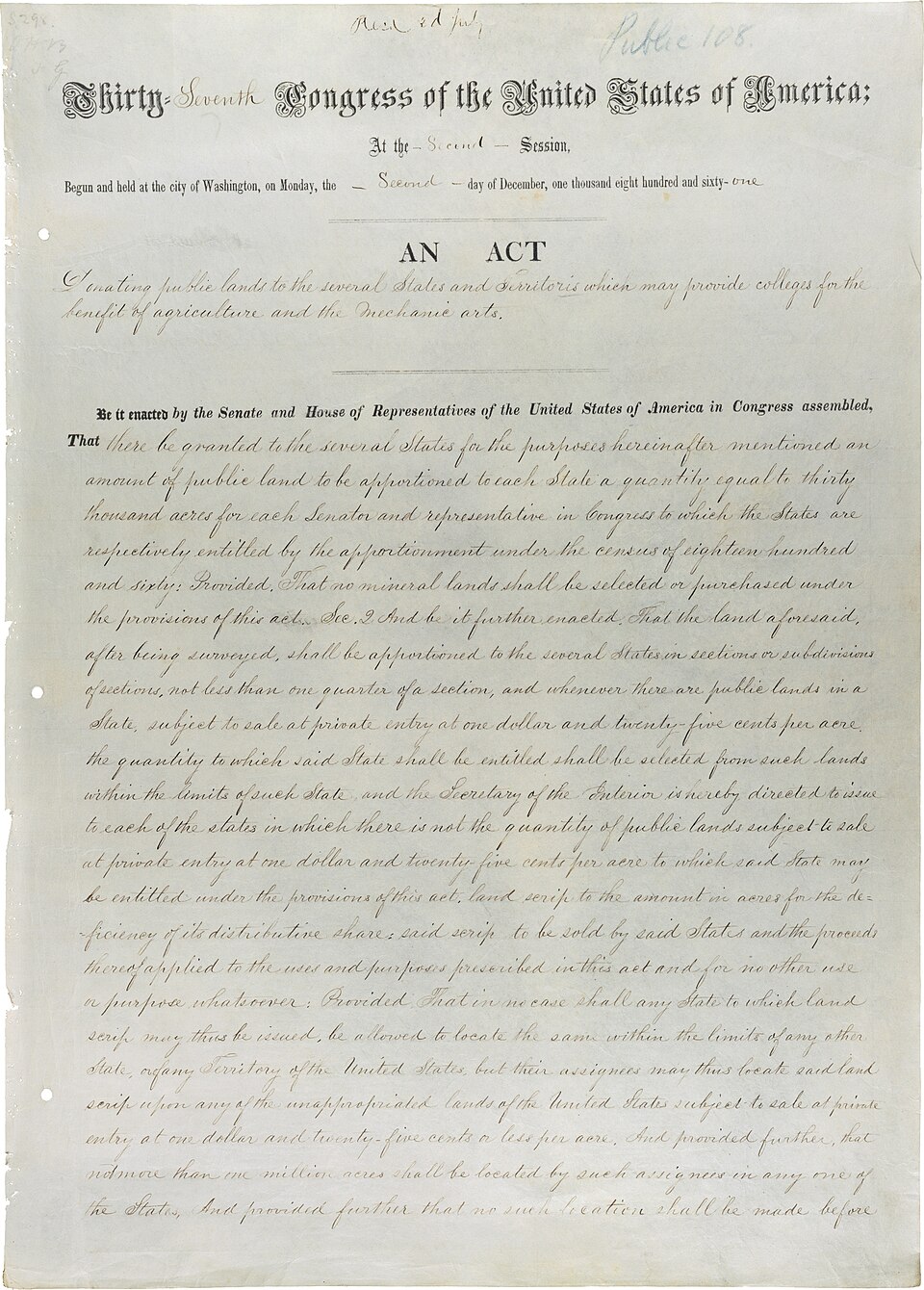

My work broadly looks at the history and politics of US knowledge production via a historical analysis of the land-grant college system. The Morrill Land-Grant Act, which was passed in 1862, was the legislative basis for the land-grant system, which “granted” 30,000 acres of land per US senator to be sold or leased to generate the start up capital for agricultural colleges in every state not in active revolt against the US government. This legislation inaugurated one of the largest mass thefts of Indigenous land in US history—close to 11.5 million acres of land, and sutured agricultural education to the settler colonial project. My dissertation intervenes in commonsense narratives of the university as an a priori good to surface its conditions of possibility, namely, the conversion of land into property and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their land. The stated purpose of the Morrill Act and the land-grant college system was to broaden access to higher education to poor white farmers, who had historically been excluded from the university. This narrative of the university as a site of upward class mobility obscures the university’s role in the reproduction of settler colonialism and racial capitalism.

Thanks for sharing! I’m curious, how did you arrive at this topic for your dissertation research?

In 2015, I took time off from my undergrad to study Spanish at a participatory language school in Guatemala, where my interest in political education and pedagogy crystallized. When I returned to school, I became fascinated by the stark differences between the pedagogical practices at Proyecto Linguistico Quetzalteco and the pedagogical practices of my university, and began to ask questions about the structural forces that constrain university pedagogies. I followed this curiosity into various political education projects outside of the university, but found myself frustrated by the limits of the non-profit model. Participating in various Indigenous-led land defense initiatives clarified the importance of developing histories of the university that foregrounded land and land-policy, and the exceptional research conducted by Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone for High Country News on the “Land-Grab University” focused my interest on the land-grant system and agricultural education. The 2020 Graduate Worker Wildcat Strike made the importance of research on the university itself in building a fighting union—for example, the University of California’s role as the largest landlord in the state is directly emergent from the land grabs that constituted its initial establishment.

As a 2025-26 THI Summer Dissertation Fellow, you conducted secondary site visits at five different universities (Michigan State University, Pennsylvania State University, University of Illinois, University of Georgia, and University of Maryland) over the summer. Why did you choose these universities as sites for your research and can you share a bit about your experience visiting them? What did the fieldwork entail?

Each of these universities lays a claim to some element of “firstness” or innovation with regard to the development of scientific agriculture as a discipline and the establishment of colleges that were specifically organized around agricultural education. Michigan State University was the first institution of agricultural education in the country (founded in 1857), and narrates itself as the model for the land-grant system. Pennsylvania State University makes a competing claim to be the model for the land-grant system, though its curriculum and pedagogy were notably different from Michigan State. The founder of the University of Illinois, Jonathan Baldwin Turner, spent the latter half of his life arguing that he, rather than Vermont senator Justin Morrill, was the true father of the Land-Grant Act. The University of Georgia was the first public university in the country, and its model of fundraising was impactful in the conception of the Morrill Act. The University of Maryland, while not explicitly an agricultural college, had been investing in scientific agriculture and its disciplinary forms in the decade prior to the passage of the Land-Grant Act. While not a comprehensive representation of the landscape of agricultural education, I chose these case studies in part due to the strength of their self-narration: in addition to archival research into the institutional history, my fieldwork consisted of going on campus tours, collecting recruitment and promotional material, and generally looking into the places where the story of the land-grant college system as a project of democratic populism held significant weight in its contemporary institutional character.

You also examined these universities’ institutional archives for your dissertation research. We’d love to learn more about the process and your time in the archives! What were you hoping to learn going in? What kind of documents were you looking at? Were there any specific materials or texts that stood out to you in particular? And in what ways (if at all) did your time in the archives change, complicate, or confirm any of your initial hypotheses?

I try to go into the archive without concrete expectations for what I will find; approaching the archive with an openness to being surprised rather than with the intent to confirm a hypothesis has been a much more generative strategy. I focused on materials around the founding and early years of land-grant institutions, looking at Board of Trustee meeting minutes, land surveys and treaty documents, publications and communications by agricultural societies, faculty recruitment strategies, and student demographic data. I was also fascinated by archival materials I found regarding the 1962 Land-Grant Centennial and the genres of commemoration and documentation that have shaped the land-grant system’s self-characterization as a democratic triumph. I’m as interested in what isn’t present in the archive as what is: recognizing the fundamentally settler-colonial character of the university also entails a recognition of the political and social forces that have constructed the archives themselves. I follow feminist and anti-colonial archival methods to critically interrogate the archive itself, recognizing that the objects that constitute the archive do not and can not tell the whole story.

Thanks so much for chatting with us, Arlo. I understand you plan to complete your dissertation by the end of the 2025-26 Academic Year. To wrap up, what would you say has been the most rewarding aspect of your Ph.D. experience? What are you looking forward to ahead?

The dissonances between the stories that universities tell about themselves (bastions of free thought, exempt from/outside of the world) and their material functions (landlord, defense contractor, police force) are deeply felt by students, and it’s been a real joy to support students in developing conceptual frames to make sense of their own experiences.

By far the most rewarding aspect of my PhD work has been teaching undergraduates. I have been fortunate to teach two classes that focus on a critical examination of the university itself, and translating my research into forms that are legible and meaningful to undergraduates as they work to make sense of their own institutional locations has been profound. I have consistently found that students are deeply hungry for material that takes seriously the experiences they have in universities. The dissonances between the stories that universities tell about themselves (bastions of free thought, exempt from/outside of the world) and their material functions (landlord, defense contractor, police force) are deeply felt by students, and it’s been a real joy to support students in developing conceptual frames to make sense of their own experiences.

Banner image: An oil painting of one of the first college buildings constructed under the 1862 Morrill Act, from the Cox Corridors at the U.S. Capitol. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.