History professor Eric Porter examines musical improvisation as a response to crisis

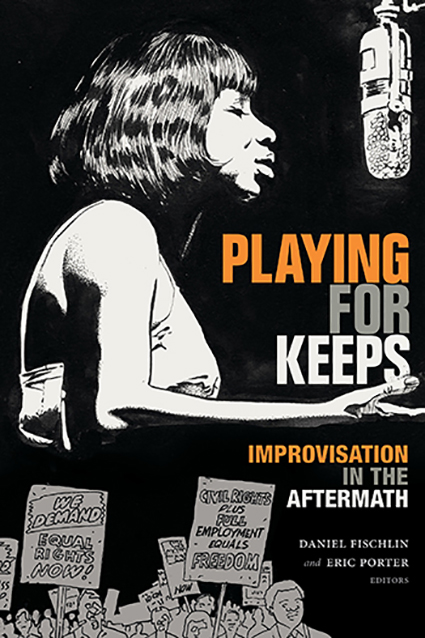

Playing for Keeps: Improvisation in the Aftermath is an exploration of the various ways that musical improvisation can be used as a method for responding to crisis and dealing with trauma and stress.

Co-edited by UC Santa Cruz history professor Eric Porter with Daniel Fischlin, the book is a collection of 12 pieces that illustrate how–in places ranging from South Africa and Egypt to the United States, Canada and the Canary Islands–improvisation provides the means for its participants to address the past and imagine the future.

“Taken together, the essays in the book look at the various ways that people have used improvisation to negotiate lingering violence and uncertainty, to address trauma, and to imagine alternative futures in the aftermaths of crises in settler-colonialism, post-apartheid, post-war, and postcolonial societies,” said Porter.

“The authors are especially attuned to the particular ways that collaborative improvisational practices–creating in the moment, together–have the capacity to build community, help people occupy and change the dynamics of public space, and generally to help people to survive and sometimes thrive amidst difficult political and social circumstances,” he added.

Eight essays are accompanied by 27 illustrations, including drawings inspired by Nina Simone’s political songs from Randy Duburke that feature images of Ku Klux Klan burning crosses, demonstrators demanding racial equality, police brandishing batons, and a man held in a police officer’s choke-hold.

The contributors include Stephanie Vos, whose “The Exhibition of Vandalizim: Improvising Healing, Politics, and Film in South Africa” looks at saxophonist/composer Zim Ngqawana and other musicians’ reaction to the burglary and vandalism of their educational institute. They responded with an improvised concert that served as a healing ritual, allowing them to work through their feelings and focus their outrage about lingering inequality in post-apartheid South Africa.

Kate Galloway’s essay shows how, in collaborations with well known experimental musicians such as the Kronos Quartet, Canadian Inuit throat-singer Tanya Tagaq uses her voice and her music as a political tool to challenge enduring derogatory stereotypes of the Inuit people shaped by colonial history.

And UCSC alum Kevin Fellezs offers a piece about the improvised, adaptive strategies Hawaiian musicians have employed over the years in music production, music education, and the recording industry to preserve their tradition and survive economically.

Playing for Keeps additionally includes a poem by saxophonist, composer and visual artist Matana Roberts, plus two interviews—one with pianist Vijay Iyer about his work with U.S. veterans of color in dealing with war trauma, and the other with two Palestinian music educators who have used music and arts education therapeutically.

Porter noted that the connection between improvisation and crisis can also be found in our current real-time social and political moment—a time of pandemic, protests against police violence and systemic racism, and deeply divided partisan politics.

“We’ve seen many examples of people improvising together to build community during the Covid-19 pandemic and current protests building from the movement for Black lives,” said Porter. “Just to name a few well-known cases that have helped people maintain social connections and encouraged perseverance during the Covid-19 lockdown: the balcony performances in Madrid, Milan, and other European cities, and the jazz jam sessions that happened for 80-something days in a row in front of saxophonist Ray Nathanson’s Brooklyn home.

“And then the music has been brought to the current protests in all kinds of interesting ways—from people playing recordings of politically resonant music, to improvised chanting and singing of protest songs and political anthems, to musicians taking to the streets themselves. One prominent example of the latter is Late Show bandleader Jon Batiste performing at protests and leading New Orleans style second-line marches in New York City. Batiste is from New Orleans, and there is a rich tradition of African American musical parading going back to the 19th century, where musicians and the second-line that follows them have asserted and celebrated their presence across urban spaces through improvisational performance and sometimes engaged in explicit political protest.”

“And, of course, the presence of music in the protests all makes sense given the long history of improvised Black music, from jazz to hip-hop, in sustaining Black life and serving as a vehicle for political mobilization and affinity for a wide range of people,” he added.

Porter is also a professor in the History of Consciousness Department at UC Santa Cruz, as well as principal faculty in Critical Race and Ethnic Studies, and an affiliated faculty member of the Music Department.

His previous books include New Orleans Suite: Music and Culture in Transition (with emeritus UCSC art professor Lewis Watts); What is This Thing Called Jazz: African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists (winner of a 2003 American Book Award); and The Problem of the Future World.

Original link: https://news.ucsc.edu/2020/08/porter-music-crisis.html