Stories in the ashes

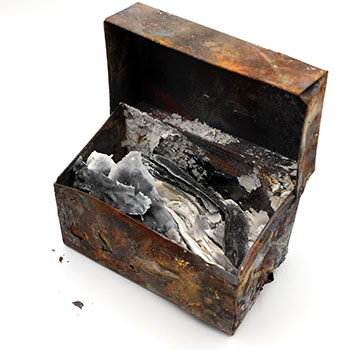

Shards of broken pottery. A pair of ice skates. A couple of scorched pedals from an old piano. A menorah used in Jewish ceremonies. A singed binder full of charred notecards. A broken ceramic bowl.

Survivors of the CZU August Lightning Complex fire have been sifting through the ashes, finding artifacts in the ruins of their lost homes.

Now those objects are helping to unlock their stories of hope and grief as part of a unique visual and oral history.

Radio producer Nikki Silva (Porter ‘73, aesthetic studies) and award-winning Santa Cruz-based photojournalist Shmuel Thaler have teamed up with the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History (MAH) for an interactive project, Lost and Found: The CZU Lightning Complex Fire Project, which collects stories of those who lost homes and businesses in the fires.

Together with MAH staff, Silva and Thaler have asked participants to bring artifacts recovered from the blazes to their interview sessions. The results have been surprising and deeply moving for Silva, Thaler, and dozens of area residents who have come forward to talk about life after a devastating disaster.

Object lesson

Silva, a longtime Santa Cruz County resident, is half of the celebrated radio production team The Kitchen Sisters, along with Davia Nelson (Stevenson ‘75, politics). The duo is known for its broadcasts on NPR and other public media.

Silva is an historian and curator who specializes in regional history. She has interviewed survivors of historic disasters, from the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake to the 9/11 terror attacks.

MAH put out a call for interview subjects to show up at the museum’s headquarters in downtown Santa Cruz for a socially distanced interview with Silva. (Silva and her subjects wear protective face masks during the sessions.)

Thaler’s photos and Silva’s interviews will reside in MAH’s historic collections for the use of historians and educators. They may also be part of a traveling exhibit.

But Silva found that the recovered objects helped the subjects tell their stories.

“It has been very moving, not just for us but for the people who have been telling the stories,” she said. “It has been amazing to see the power of the objects they bring to the interviews. What does it mean when something emerges from the ashes? It takes on an extraordinary meaning. Why was this saved? Why is this object talking to me? What is my memory of it? How does it relate to the things I lost?”

Each subject provides a different vantage point to the fire. One recent participant is a retired firefighter who helped battle the Lockheed Fire that swept through Swanton and Bonny Doon in the summer of 2009.

“And he’s never seen anything like this,’’ Silva said. “He was just astonished by it.

“One person talked about her 16-year-old son, who had gone up with the express yearning to find this Boy Scout knife that his father had given to him,” Silva said. “That is all he wanted. And he found it, and the handle melted, but there you go. He had a vision of what he needed.”

When Cari Napoles (Porter, ‘91, American studies), senior director of development for UC Santa Cruz’s Humanities Division, came in for her interview, she held a pair of Japanese Shisa dog sculptures she bought on a trip to Okinawa as part of the Okinawa Memories Initiative, a UC Santa Cruz public history project focusing on the U.S. military occupation of Okinawa.

“They have this incredible meaning behind them, these two little dogs that stand guard like little lion dogs,” Napoles said. “People put them at their doorways and in front of their gates.”

Napoles lost her home in Davenport during the fires.

Photographic memories

Thaler has been taking images of the found objects.

“Shmuel Thaler is an extremely beautiful photographer,’’ Silva said. “These artifacts are like objects of art. They are totemic. They are not photographed ‘in situ’—at the site of the fires. They are photographed at the museum. When they are isolated in this way, they take on a different meaning.”

COVID-19 has added logistical challenges to the interviews.

“Usually when I am interviewing someone, I am right in their face, and sitting really close,’’ Silva said. “We can’t do that. I have a six-foot boom pole and we’re all wearing masks and have a table between us in the big atrium of the museum. Everything is sanitized, and we change the microphone’s windscreen between interviewees, so we’re being very careful.”

Considering the painful subject matter and the need for precautions during a time of pandemic fears, Silva wasn’t sure who would show up and what to expect.

“It’s difficult for people to talk about something so intensely personal and terrifying,” Silva said. “I didn’t know if people would want to come or what it would be like if they did come.

“But it’s been very moving, not just for us but for the people who come here to share their stories with us. Everyone has said how important it has been just to talk about it. It’s like all of us when anything horrible or traumatic happens. You just have to tell the story over and over. It settles in you, and you can figure it out. And using objects is an amazing way to do it. It brings back memories and associations.”

The power of voice

But the talks with Silva are much more than therapy sessions. They are vividly detailed and evocative accountings of a fire and its aftermath, going far beyond newspaper clippings and statistics.

“From the standpoint of the historical record, this project is so valuable,” Silva said. “So much of the time, we have something one person wrote, or one person filmed, from just one vantage point. But this project gives us so many perspectives on the fire.

“I’ve been doing audio storytelling for years,’’ she said. “And there’s something about the voice that is not like the written word. There are other depths, beneath the words, and it all comes through for me—the informational, the descriptive, the emotional. There are just so many layers.”

Original Link: https://news.ucsc.edu/2020/11/nikki-silva-fire-interviews.html