Travel Series: Maziar Toosarvandani

Maziar Toosarvandani is Associate Professor of Linguistics at UC Santa Cruz. His primary research interests are in syntax and semantics, with an empirical focus on two Indigenous languages of North America, Northern Paiute (Numu) and Southeastern Sierra Zapotec (Dille’xhunh). His current projects investigate the linguistic principles governing narrative structure, the grammatical representation of animacy, and variation in temporal meaning. Dr. Toosarvandani’s papers have appeared in Language, Linguistic Inquiry, the International Journal of American Linguistics, and Semantics and Pragmatics, among other journals. As part of his commitment to creating knowledge with and for language communities, he maintains online dictionaries and text collections for the Mono Lake variety of Northern Paiute and Santiago Laxopa Zapotec, resources which can be used by community members for learning or teaching their language and by linguists for answering research questions. He has also been involved in Nido de Lenguas, a THI sponsored project which organizes events for the public to learn about the Indigenous languages of Oaxaca, in collaboration with local nonprofit organization Senderos.

Talking Tense / Feeling Time

We don’t always have to move our bodies to go somewhere. Anytime we pick up a novel or listen to a friend tell a story, we can be transported to a different place instantly, far faster than it would take to walk.

We can even move through time in this way. With language, we can talk about what took place at some distant time in the past, or make plans for the future.

The ability to travel to other times and locales, limited only by our imaginations, appears to be a universal feature of human language. While many animals communicate about their immediate circumstances — songbirds and chimpanzees, among them — only humans seem to use language to talk about other times and places. Honeybees may come closest to us in this respect. They dance to communicate to their hivemates where they found their most recent food source. But no matter how hard it dances, a honeybee still can’t communicate where it found the best pollen last year, nor share its guess about where it might encounter some particularly productive flowers tomorrow.

This idea, that our language shapes our thought, was eventually dismissed by scholars in Whorf’s time. But it has kept a grip on our imaginations ever since.

In many languages, this displacement is aided by distinct verb forms for describing when an event takes place. English has two of these tenses. There are verb pairs like dance–danced, ask–asked, and so on — alongside more irregular pairs like sing–sang and see–saw. For future events, things are a bit simpler, all we have to do is add will.

Not all languages have these two tenses. Some, from different parts of the world — North and South America, East Asia, West Africa — have no present or past tenses at all. In the 1930s, a fire insurance agent named Benjamin Lee Whorf, from Hartford, Connecticut, hypothesized that speakers of these languages don’t just talk about time differently, they also think about time differently.

This idea, that our language shapes our thought, was eventually dismissed by scholars in Whorf’s time. But it has kept a grip on our imaginations ever since.

Whorf’s interest in language differences began early, and continued throughout his life, even as he pursued a career in chemical engineering.

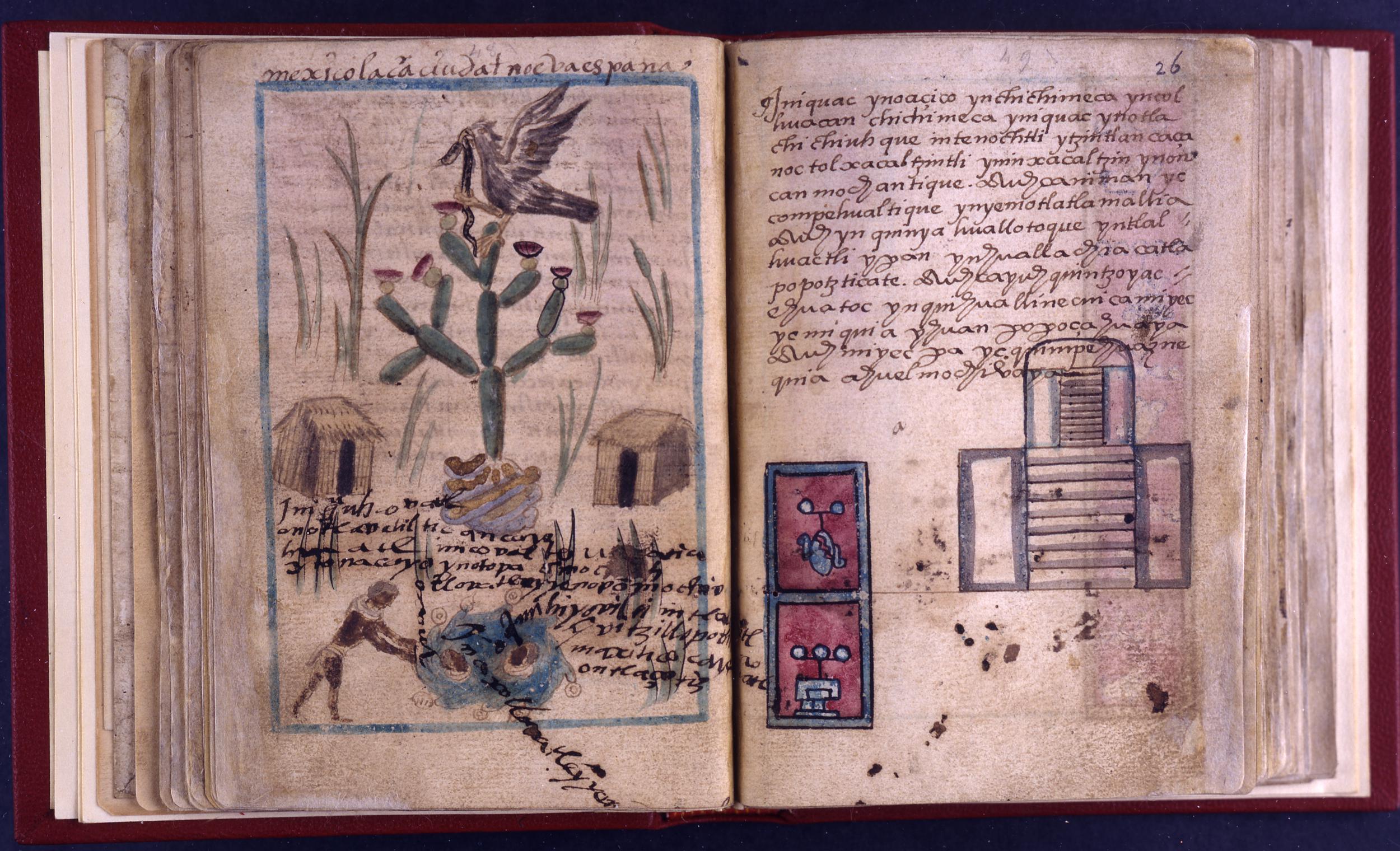

He was a frequent visitor after work to Hartford’s Watkinson Library and its unusually large Classical Nahuatl collection. Created by Indigenous authors in the years after Spanish colonization, these manuscripts integrated pre-contact writing traditions with Nahuatl, written in a Latin script.

The language of the Mexica people of Tenochtitlan is no longer spoken, but its contemporary cousins are. Over a million people across central and southern Mexico speak a Nahua language today. Whorf spent several weeks in 1930 studying one of them, inspired by his library explorations, despite never having received any formal training in linguistics.

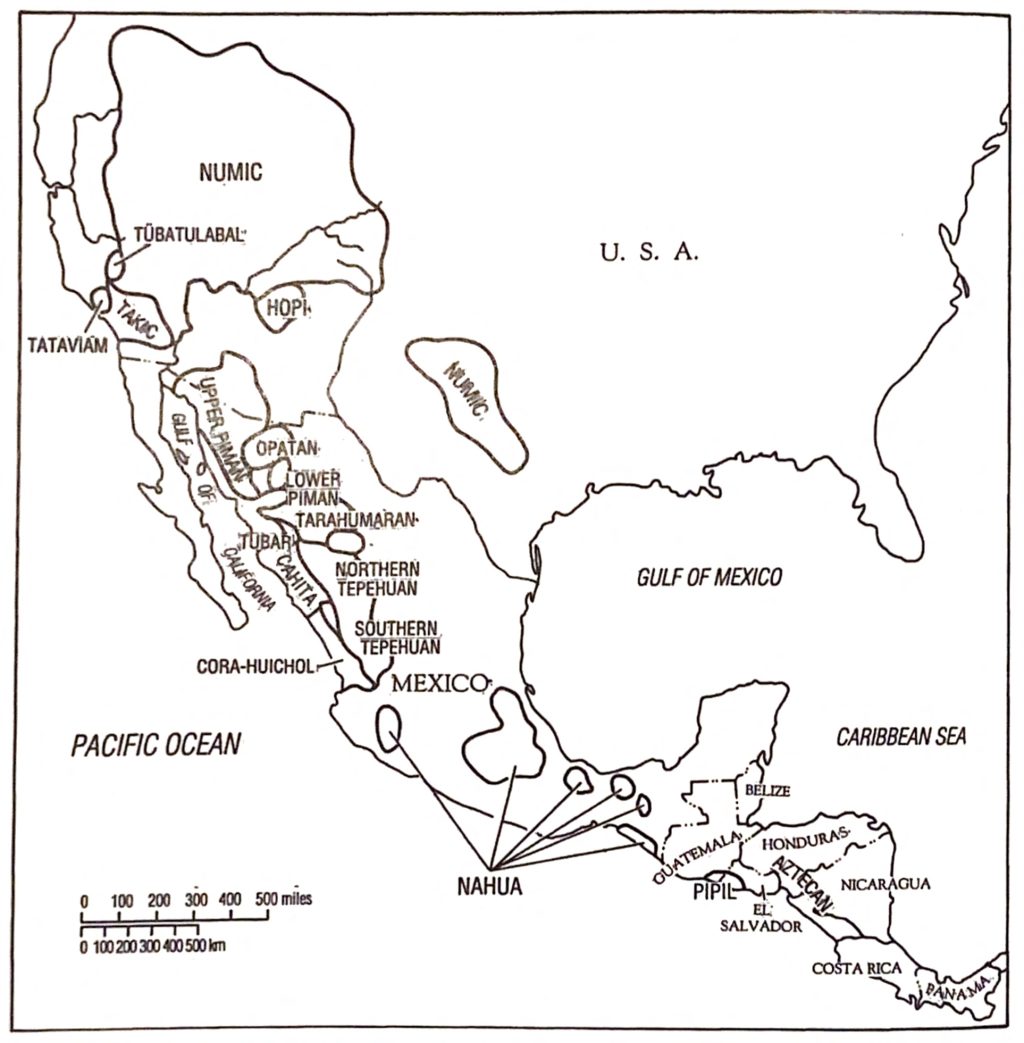

Upon returning home, he enrolled in graduate classes at Yale University, where Edward Sapir, an accomplished scholar of American languages, had just taken up a post. Some years before, Sapir had demonstrated that dozens of languages from across western North America, including Nahua, belong to a single language family and share a common ancestor. This proto-language was most likely spoken roughly 3,000 to 5,000 years ago, somewhere between the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts, in a community of foragers and hunters. Its descendant languages have come to be spoken where they are today through migration — some, like Nahua, to the south and others to the north.

With Sapir’s encouragement, Whorf undertook the study of some of these Uto-Aztecan languages. He was surprised to learn they had many grammatical features which make them different from the European languages he was familiar with.

The complex verb inflections in Hopi, spoken today by around 6,000 people, made a particularly strong impression on Whorf. The language has an array of prefixes and suffixes, not found in English, for describing an event’s duration or intensity, how it is composed of smaller events, and whether an event is ongoing, just beginning, approaching completion, or just completed.

He also observed there are some verb forms which Hopi does not have. It has no tenses for describing whether an action takes place in the past or present.

To Whorf, these language differences were not superficial. In a series of influential articles, he hypothesized that a language’s lack of tense also shaped its speakers’ perception of the world. Without tense, he supposed, they might have “no general notion or intuition of time as a smooth flowing continuum…out of a future, through a present, into a past.”

So the hypothesis of linguistic relativity, as it came to be known, was born.

In its strongest form, it maintains that the words and grammatical categories available in one’s language determine how one perceives the world. Within linguistics it enjoyed only a brief period of interest, for a few years after Whorf’s death in 1941. By the 1960s, it had already been set aside as a serious research question.

To be sure, languages differ in countless ways. But to demonstrate that language determines thought, linguistic differences must be correlated with some testable language-independent differences. Over the years, numerous experiments to uncover these were attempted, but their results were inconclusive.

Perhaps no particularly sophisticated experiment is even really needed to show that Whorf’s hypothesis, in its strongest form, can’t be right.

Alongside languages with no tense, there are also languages with much richer tense systems than we have in English. In the Mvskoke language, spoken today by around 4,500 people in Oklahoma, four past tenses describe how far in the past some event took place.

Recent Past -h- or -i- or -iy- ‘just now’

Middle Past -mk ‘from yesterday to a year ago’

Distant Past -mvt ‘from yesterday to a long time ago’

Remote Past -vtē ‘from yesterday to the mythic past’

Mvskoke is far from alone in this respect. Many unrelated languages from across the Americas, Southern Africa, and New Guinea have two or more past tenses.

If the grammatical categories in our language really determine how we think about the world, then speakers of English would seem to have a real problem, with just their single past tense.

But obviously, this doesn’t stop you or me from thinking about when in the past something happened. I don’t confuse when I may have bought a fudgie in Stevenson Coffee House (yesterday) with when I had my last dental cleaning (a little more than six months ago), or when I graduated from college (in the distant past, apparently, twenty years ago).

In recent years, some psychologists and linguists have taken up a much weaker version of linguistic relativity. Using behavioral experiments, they are looking for subtle ways — measured in milliseconds — that language differences might influence comprehension, as reflected in a subject’s response times or involuntary eye movements.

Their results aren’t conclusive yet, but it’s clear they’re investigating a hypothesis far less alluring than Whorf’s original conjecture.

A focus only on language differences also overlooks a basic fact about our linguistic competence.

Before Whorf ever started his studies of Hopi, a Pyramid Lake Paiute man named Gilbert Natches arrived in Berkeley. He came, in 1913, to help anthropologists at the university interpret some manuscripts in their possession. When this work ran into difficulties, Natches turned his attention instead to creating a literature for his language.

Natches was a speaker of the Pyramid Lake variety of Northern Paiute, a relative of Hopi and Nahua, spoken across the western Great Basin. For many years, I worked with elders living just north of Mono Lake, in eastern California. They spoke a Northern Paiute variety that was not so different from Natches’.

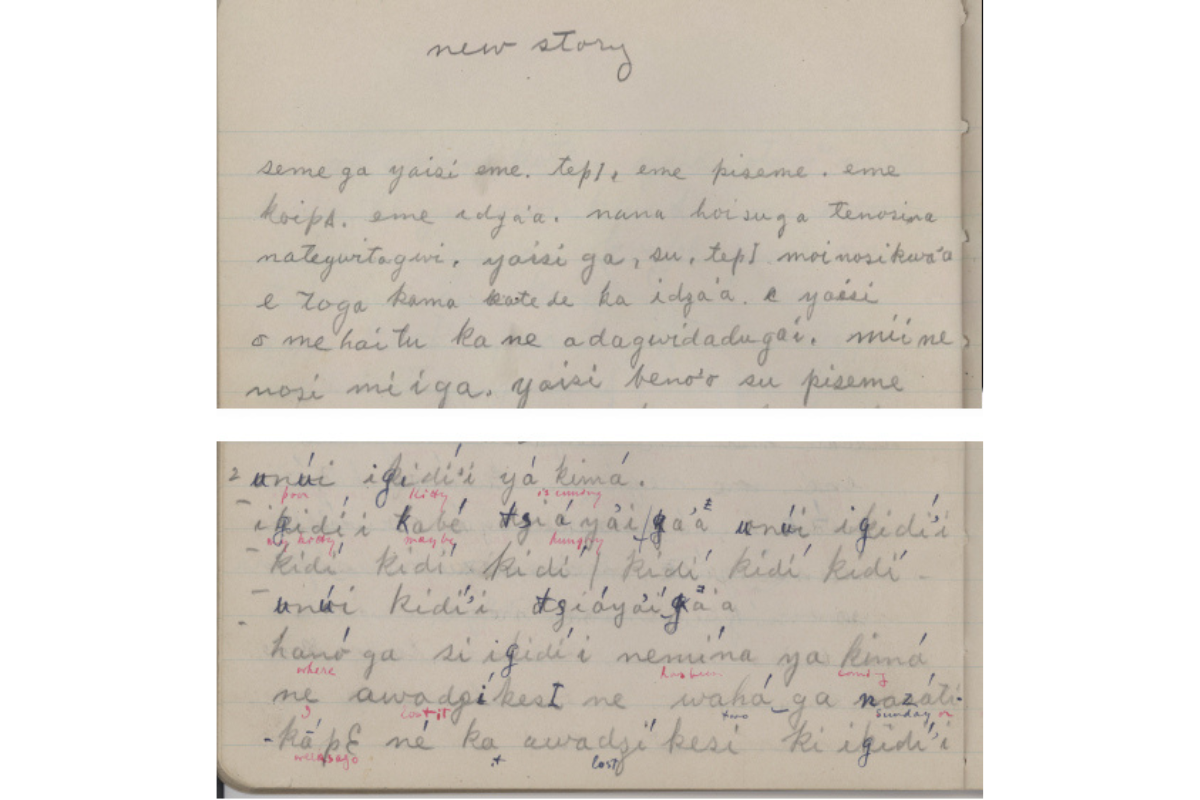

Over a two year period, Natches set down a dozen texts in a small notebook, using a writing system for his language that he had learned while at Berkeley. Several of these he also recorded on wax cylinders.

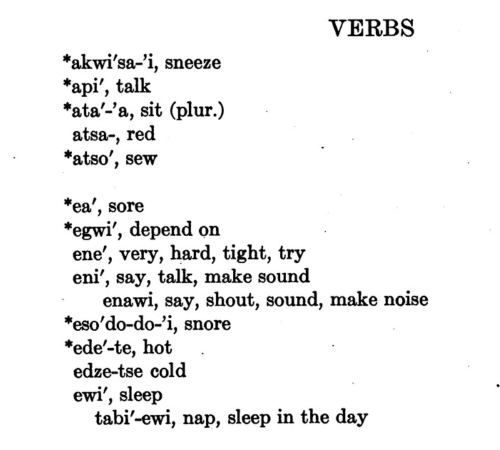

Some of Natches’ stories were published later in an academic journal, accompanied by a list of verbs. He listed just one form for each verb, perhaps because he recognized that his language has no tenses, just like Hopi.

In his notebook, Natches chose to write down several different types of texts. Some may have interested the anthropologists he was working with. But some were, clearly, just important to him.

There are several traditional stories, recounting events in the mythic past about Cottontail, Dove, Owl, Coyote, and others. But there are also texts which take place at other times. He wrote down two imagined conversations, one between himself and his cat. He asks his cat whether it’s hungry, imitating its responses, and entertains it by whistling. There are some of Natches’ own stories, too. One describes a wagon accident he got into, while fishing for trout. Another, which he titled “New Story,” features Coyote talking to Flint and Bighorn Sheep about their dreams (at the end of which Flint ends up shattered in small pieces).

Natches created one of the first written literatures for his language, and building on it, the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe today is working to increase fluency in Northern Paiute. The Kooyooe Tukadu Numu Yadooana program is creating teaching materials for the language, which it uses in classes for the community and in schools.

Without tense, is the line between the past and the present really so hopelessly blurred?

Natches’ legacy shows us what perhaps should have been clear from the start. Some languages have many tenses, some have none at all. But these differences don’t hinder our linguistic creativity. They don’t stop us from sharing our experiences with others, telling stories about who we are, and imagining new ways of being and doing.

Acknowledgements

The discussion of Gilbert Natches’ life and linguistic legacy was inspired and informed by a chapter in Andrew Garrett’s forthcoming book The Unnaming of Kroeber Hall: Language, Memory, and Indigenous California (MIT Press), as well as its adaptation for the California Language Archive blog. Natches’ notebook is archived at the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages (Item: Marsden.015), and the recordings of his conversation with his cat and “New Story” can be found at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at UC Berkeley (Items: 24-2306 and 24-2289). The discussion of Benjamin Whorf’s life and ideas draws on Stephen C. Levinson’s preface and John B. Carroll’s introduction in Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf (second edition, 2012, MIT Pres). Whorf’s quote on time in Hopi comes from his article “An American Indian model of the universe,” published posthumously in the Internal Journal of American Linguistics in 1950 (16:67–72). Information about the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe’s language program came from the Kooyooe Tukadu Numu Yadooana website. The history of Uto-Aztecan is discussed in Simon J. Greenhill and co-authors’ recent article, “A recent northern origin for the Uto-Aztecan family” (2023, Language 99:81–107). The Mvskoke’s examples came from Pamela Innes, Linda Alexander, and Bertha Tilkens’ (2004) Beginning Creek: Mvskoke Emponvkv (University of Oklahoma Press). The typological generalizations about tense come from the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) Online.

Banner Image: Mono Lake, in eastern California, looking northward.

“Talking Tense / Feeling Time” is part of The Humanities Institute’s 2023 Travel Series. This series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti in the Humanities community at UC Santa Cruz – each of whom highlight connections between travel and their work or consider the role of travel in their fields. Throughout Spring quarter, be sure to look for these amazing essays in our weekly newsletter!