Imagination Series: Micah Perks

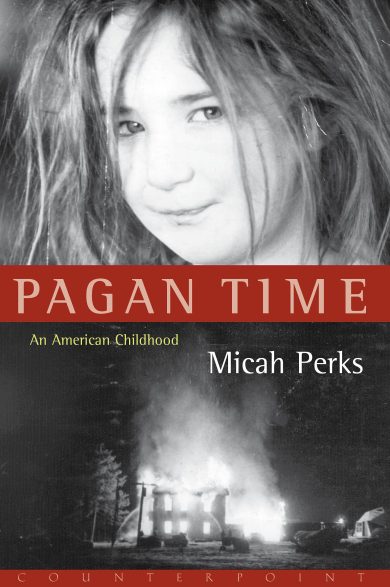

Micah Perks is Professor of Literature and the Director of the Creative Writing Program at UC Santa Cruz. Her research and writing focuses on U.S. fiction, autobiographical writing, historical fiction, and U.S. utopian communities. Perks is the author of multiple books, such as What Becomes Us (2016) and the memoir Pagan Times (2001). She is currently at work on another novel, The Wood Between the Worlds, about an ambiguous utopian revolution in the near future. Perks’ contribution to our 2022 Imagination Series explores the possible meanings –both good and bad– of the oft-used word utopia and ultimately encourages us to express our more ambiguous utopian imaginations.

Micah Perks is Professor of Literature and the Director of the Creative Writing Program at UC Santa Cruz. Her research and writing focuses on U.S. fiction, autobiographical writing, historical fiction, and U.S. utopian communities. Perks is the author of multiple books, such as What Becomes Us (2016) and the memoir Pagan Times (2001). She is currently at work on another novel, The Wood Between the Worlds, about an ambiguous utopian revolution in the near future. Perks’ contribution to our 2022 Imagination Series explores the possible meanings –both good and bad– of the oft-used word utopia and ultimately encourages us to express our more ambiguous utopian imaginations.

A Few Notes on Imagining Ambiguous Utopias (after Ursula)

Maybe it’s the beginning of the end. Maybe we’re played out. Is that what you’re thinking? Because sometimes that’s what I’m thinking.

I’m trying to think another way.

In his memoir, C.S. Lewis describes his first experience of joy when, as a very young child, he saw a miniature garden constructed by his older brother. He describes his feeling upon gazing on that tiny world as closest to “Milton’s ‘enormous bliss’ of Eden.”

I can imagine the orderly green rows of that miniature garden, how pleasing in its perfection. The enormous joy of a tiny Versailles, so managed, so controlled.

As Ursula Le Guin writes, utopias are most often “sites of maximum control.” Worlds imagined around rules, isolated, protected by walls. The Hebrew word for “holy” means separated, cut-off. Maybe that’s why utopian literature is often so boring. As David Byrne sings, “Heaven is a place where nothing ever happens.”

Utopia is a Greek word coined by Thomas More in the sixteenth century, meaning no place. But no one really knows if Thomas More’s Utopia was a joke or if he was imagining in earnest. For example, in his Utopia they executed adulterers after the second offence. Once was okay. Some people think he actually meant to write eutopia—which means good place and is pronounced the same way– and by mistake spelled it utopia—no place. That’s something I would do. More’s island Utopia is pretty brutal, but not as brutal as sixteenth century England where More purportedly tortured Protestants and was later beheaded by Henry the Eighth.

“The organizing principle of dystopian fiction is that the imagined world is worse than our own…Maybe that’s why they’re so popular—it makes our world the happy ending.”

Everyone loves a dystopia, except me. Dystopias are the negative nellies of the speculative fiction world. The organizing principle of dystopian fiction is that the imagined world is worse than our own. Dystopias are inherently conservative because they give us the feeling that wherever we find ourselves is not as bad as the imagined dystopia we’re reading about. So we close the book feeling pacified. Maybe that’s why they’re so popular—it makes our world the happy ending. I think I stole this idea from Darko Suvin.

Imagining apocalypses, on the other hand, is fun, because they’re childish wish fulfilments, fast tracks to utopia—erase everything and start over. Earthquakes. Zombies. Alien Invasion. Ants under a magnifying glass. Automatic do over.

I’m interested in the original meaning of apocalypse as revelation, as radical transformation, and on utopic visions and experiences within and after apocalypse. Although many utopias are imagined as impossibly static cultures, I follow Ursula Le Guin, who wrote that utopia “is process not stasis.” I imagine communities that form and reform and dissolve around dreams of symbiotic perfection.

The original subtitle of Ursula Le Guin’s novel The Dispossessed is “an ambiguous utopia.” I like the introduction of ambiguity when imagining utopias. As in inexact. Utopias that are possibly better, that are in process, but not perfect nowheres.

I’m writing a novel called The Wood Between the Worlds about an ambiguous utopian revolution in the near future, like, next year maybe. I’m trying to imagine a more fun and better future. I ask everyone I meet, what is your dream for a better future? What innovations can you imagine?

A scientist told me about bacteria that eat plastic. What about a land bridge over cities for animal crossing? Factories that are also amusement parks. Public school teachers making the big bucks. Abandoning half the earth to heal.

What is the relationship between the utopias we write about and the worlds we actually live in? California is named after an island in a sixteenth century novel, The Adventures of Esplandian, a utopian island of black women ruled by the warrior queen Calafia.

Utopias can be dangerous. Nazis, Stalinists, Make America Great Again.

Alanis Morrisette’s song utopia:

We’d gather around

All in a room

Fasten our belts

Engage in dialogue

We’d all slow down

Rest without guilt

Not lie without fear

Disagree sans judgement

That’s what I’m talking about in terms of the danger of utopias boring us to death.

The UCSC creative writing program as ambiguous utopia: Our intern, Khushal, said we should change the name of the Living Writers Series to the Loving Writers Series. Great idea, Khushal.

Utopianists are smirked at by some for their unwillingness to see the world as it is. Rose colored glasses is a metaphor for not seeing clearly. That’s a little dumb. Every utopia is a critique of the world as it is.

In one of my large lecture classes I asked all my students to draw pictures of utopia. I got almost 300 drawings of stick figures holding hands encircling the globe. Something I’ve been wondering about, after Thoreau: what role does solitude play in an ambiguous utopia?

Exercise your ambiguous utopian imaginations. Partly as refuge, partly to imagine a way out of this mess we’ve gotten ourselves into.

What is your dream for a better future? What innovations can you imagine?

Some further fun Ambiguous Utopian readings:

Le Guin:

The Disposessed

Always Coming Home

“The Shobies Journey”

“Solitude” (my absolute favorite Le Guin story)

“Black Betty,” by Nisi Shawl

“The Ones Who Stay and Fight” by NK Jemisin

Lilith’s Brood by Octavia Butler

Ministry for the Future and Shaman by Kim Stanley Robinson

The Great British Baking Show

Station Eleven, the television show, not the book

“A Few Notes on Imagining Ambiguous Utopias (after Ursula)” is part of The Humanities Institute’s 2022 Imagination Series. This series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti in the Humanities community at UC Santa Cruz – each of whom highlight connections between imagination and their work or consider the role of imagination in fashioning new worlds. Throughout Spring quarter, be sure to look for these amazing essays in our weekly newsletter!