Imagination Series: Zac Zimmer

Zac Zimmer is an Assistant Professor of Literature at UC Santa Cruz and is affiliated with the Spanish Studies, Legal Studies, and Latin American & Latino Studies programs. He is a scholar of twentieth- and twenty-first century hemispheric literature and culture, focusing on how speculative and science fiction texts question knowledge paradigms and aesthetics associated with the Conquest of the Americas. His research brings into view the understudied genre of hemispheric speculative fiction alongside genres that have come to popularly define twentieth-century Latin American literature, including magical realism, the historical novel and postmodern metafiction. With his comparative research linking continents, histories, languages, genres, and aesthetic traditions, as well as an attention to technology and media studies, Professor Zimmer brings a transnational and transdisciplinary orientation to Latin American literary studies.

Zac Zimmer is an Assistant Professor of Literature at UC Santa Cruz and is affiliated with the Spanish Studies, Legal Studies, and Latin American & Latino Studies programs. He is a scholar of twentieth- and twenty-first century hemispheric literature and culture, focusing on how speculative and science fiction texts question knowledge paradigms and aesthetics associated with the Conquest of the Americas. His research brings into view the understudied genre of hemispheric speculative fiction alongside genres that have come to popularly define twentieth-century Latin American literature, including magical realism, the historical novel and postmodern metafiction. With his comparative research linking continents, histories, languages, genres, and aesthetic traditions, as well as an attention to technology and media studies, Professor Zimmer brings a transnational and transdisciplinary orientation to Latin American literary studies.

The Colombo ex frigata and Imagining Contact Beyond Conquest

As an undisciplined scholar of technology and culture, I’ve always relied on my imagination to guide my research. I am also guided by my training, which is a mixture of Latin American cultural studies, science and technology in society, and political theory. Even before I arrived at UC Santa Cruz, my research had led me to one of the hallmark pieces of wisdom produced by the UC Santa Cruz Cultural Studies endeavor: It matters which stories we use to think about our technologies.

There is a particular story about the Americas that has always bothered me, as someone who traveled and studied the length and width of that great hemispheric continent. It is the story of European technological supremacy in the sixteenth-century Conquest of the Americas. That story is partial at best, and it is certainly limited in its imagination.[1] And yet, notwithstanding the many attempts to debunk those myths and correct the record, there remains a widespread misconception about the sequence of events set in motion in 1492. Our ability to imagine the past and the future of the Americas—South, Central, and North—suffers greatly because of it.

This kind of speculative imagination of historical events can reveal realities that are otherwise covered over by dominant narratives.

I spent time thinking about how to escape the kind of technological determinism that would only allow the imagination to think of the Conquest as the inevitable expression of some kind of relentless historical logic. What I found was that speculative fiction (SF) provided an entry point to reimagine the Conquest, in a way that engages the dense complexities and contradictions of that historical period.[2] I began to assemble a collection of SF narratives and art that explored the Conquest not through some prefabricated explanatory alliteration—microbes, munitions, and metallurgy, for instance—but rather in a way that thinks that historical period as one of emergence and emergency. This kind of speculative imagination of historical events can reveal realities that are otherwise covered over by dominant narratives. SF is even more powerful than historical fiction (or its postmodern descendent, historiographic metafiction) in that by reimagining the past, SF can unlock the potentiality of unrealized historical possibilities.

This led me to write a book that studies authors and artists who use speculative and science fiction (SF) to reimagine how the Conquest could have been different. In the book, called First Contact: Speculative Visions of the Conquest of the Americas, I interpret authors like Carmen Boullosa, who imagines a time-traveling Moctezuma returning to late-1980s Mexico City; and Wilson Harris, who restages the fateful encounter between the Inca Atahualpa and the Spanish Conquistadores not in Cajamarca but rather in an allegorical dream space. I recuperate strange works of alternative history, like a Mexican novel written in Catalan by a Republican exile that tells the secret history of the Aztec conquest of Mexico.

I also study narrative tropes like “Jesuits in Space” which frequently appear in these stories. The name of that particular trope—which pops up across a wide variety of SF, from mid-twentieth century “hard SF” to highbrow literary bestsellers—does a great job capturing exactly what it’s about. Perhaps due to the Jesuit predilection to sprint towards any contact zone in the early waves of European colonization, SF authors have a habit of sending Jesuit characters to space when they write extraterrestrial colonization stories. Once the Jesuits are off-planet, the authors use those characters to explore thematic conflicts between science and faith. In the book, I focus on Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow as exemplary of the trope.

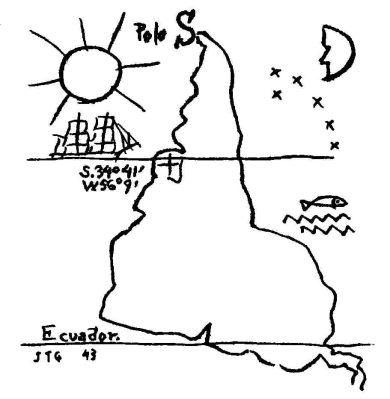

America invertida, 1943

Another trope that I study in my book has a less transparent name. I call it the “Colombo ex frigata.” That trope is connected to Christopher Columbus, and has everything to do with the limitations of our historical imagination. Columbus is a figure of debatable importance in the history of Latin America. I do not say this dismissively, but rather descriptively. The debate over what Columbus means for the history of the landmass once called The New World has developed significantly since the global protests surrounding the 1992 Quincentenary celebration. In the twenty-first century, Columbus himself has become a figure who represents a certain kind of white, patriarchal, colonial mindset that, furthermore, has organized a historiographic project of erecting monuments consecrated to false histories.[3] Those are the monuments that must be symbolically toppled, as The Monument Lab has amply documented.

And yet it is not clear to me that the SF imagination is fully beyond Columbus. When I talk broadly about SF that reimagines the Conquest, this includes the contemporary wave of decolonial worldbuilding that understands itself as an act of political imagination. It includes all of the speculative work highlighted and uplifted by the Beyond Columbus Foundation. But it also includes the SF tendency to posit Columbus as the recurring protagonist in stories about imagined first contact.

It is not only SF authors who participate in the metonymy, where the name Columbus comes to stand as a shorthand for a particular interpretation of the meaning of 1492 and its aftermath. Columbus appears all over environmental history—the Columbian Exchange, for instance—and across political theory. But it is particularly in the realm of SF that Columbus seems to have the most enduring presence as a symbol of “first contact” narratives.

I began to notice a particular kind of SF story, which played off of this metonymic identification of Columbus with the novelty of the colonial encounter. It had elements of the classic Deus ex machina, where an unexpected interruption leads to the abrupt resolution of a narrative. But these stories also exhibited some of the pulpier elements of what Brian Aldiss called the Shaggy God tale. For Aldiss, the emblematic Shaggy God story–the definitive hack pulp trope of bad SF–entirely relies on the impact of the revelation that two strange alien lifeforms–a couple, of course–have been released into an empty world to populate it, and their names are—surprise!—some variation of Adam and Eve.

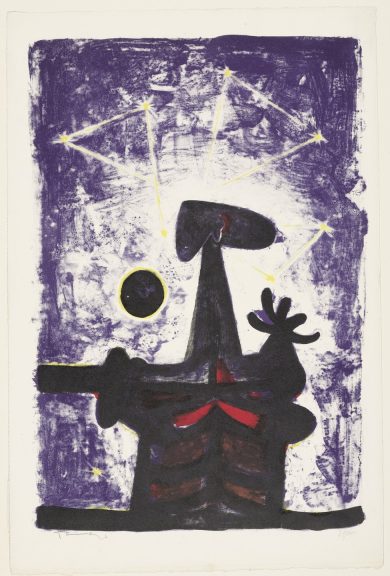

Man, Moon, and Stars (1950)

The Columbo ex frigata does not rely on a disguised Garden of Eden. It is specifically connected to the ship, hence the “frigata” of the title, a multilingual rendering of frigate and fragata. José Adolph, who has been anthologized in the seminal Cosmos Latinos: An Anthology of Science Fiction from Latin America and Spain, wrote a memorable version of the Colombo ex frigata in his story “Persistencia.” Adolph counts on his readers associating his name with SF, so that it will be no surprise when the story opens with three pages of philosophical and pseudoscientific reflections from a spaceship captain. After recalling the war and destruction he left behind, imagining the future that his ship and his crew will open up through its journey as “naked creatures, floating through creation,” and recounting the trials and tribulations they have faced on what clearly seems to be an interstellar voyage, he concludes his captain’s log with a dedication to the Catholic Church and the Spanish Crown, and stamps the date: October 1492. Our galactic ship captain has been none other than the Genoese Admiral! It is the specific plot device of this revelation which I call the Colombo ex frigata.

Carlos Fuentes has his own version, which he uses as the centerpiece of his thematic collection of short stories El naranjo, o los círculos del tiempo [The Orange Tree]. Mario de Andrade spoke of A dor irreconciliávil humana, que viajara na primera vela de Colombo [The irreconcilably human pain that traveled on Columbus’ first ship]. Angélica Gorodischer’s chapter “De Navegantes” in Trafalgar is one of my personal favorites, as Gorodischer recasts Columbus as her charming protagonist Trafalgar Medrano, a galaxy-hopping merchant from Rosario, Argentina. Beyond Latin America, even Cixin Liu uses an image of the Colombo ex frigata as the narrative hinge at the mid-point of his extraordinary Three Body Problem series.[4]

The appeal of the Colombo ex frigata is that it allows for a quick and easy SF staging of what Diana Taylor calls the “scenario of Discovery.” These are the scenes of so-called “first contact” that were repeated throughout the early European colonization of the Americas in order to claim European dominion and sovereignty over territories to which they had only recently arrived. The fact that a “first contact” or “first encounter” could itself become a ritualized performance, as Taylor convincingly argues, gives the lie that these moments were ever really truly the “first time.” The concept of “firstness” itself, as Jean O’Brien demonstrates in Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England, is always articulated in the service of the dual project of settler supremacy and the erasure of prior indigenous presence.[5]

That is why in my book, I focus on art and narrative that pushes and pulls contact SF beyond Columbus to imagine other ships, other journeys, and other encounters.

And so when SF uncritically adopts the Colombo ex frigata as a readymade way to write a story of intergalactic encounter, it perpetuates a legacy of false terrestrial history and at the same time limits the literary imagination of other possible futures. That is why in my book, I focus on art and narrative that pushes and pulls contact SF beyond Columbus to imagine other ships, other journeys, and other encounters. And examples abound, like the art showcased in Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas, especially the capsules that artists Beatriz Cortez creates to harbor safe passage for true talk about the history that we “Americans” bring forward in our shared journey towards a different future. Or a novel by former UC Santa Cruz professor Gerald Vizenor called Heirs of Columbus, a devious and playful text that speculates Columbus as a Mayan-born continental trickster.

These are stories of different vessels and different navigators. They use SF to retell historical origin stories in ways that open up new and different possibilities for the future. This is a newness that is not grounded in some kind of eternal Columbian firstness. Instead, these works explore the newnesses that emerges when we speculate beyond the histories we already know to be lies. Darko Suvin memorably said that all science fiction must contain a “novum”, some kind of “new thing”—whether technology, discovery, ideology, or even physiology—that defines the SF component of a narrative. As the Columbo ex frigata trope shows, the very idea of “first contact” in SF colonial encounters is an old colonial trope. It is only beyond the Colombo ex frigata that SF can ground itself in a decolonial novum.

[1] Matthew Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest.

[2] I follow UCSC’s Donna Haraway in understanding SF in a deliberately broad fashion which encompasses science fiction, speculative fiction, and, in the case of the Latin American narratives I study, what Julio Cortázar called lo fantástico.

[3] In popular meme culture, this has been condensed and reduced to the delightfully tautological “Columbus columbused America.”

[4] “The ship of human civilization floated alone in the vast ocean, surrounded on all sides by endless, sinister waves, and no one knew if there even was an opposite shore” (Liu, The Dark Forest 2015 p. 305).

[5] My book’s half-millennial perspective that focuses on the medium-term—not the untimely present, nor continental deep time—is of course a middle ground. It needs to be complemented by the long historical perspective from books like Paulette Steeves’ The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere, for instance, in addition to the work by my colleagues in Indigenous and Native Studies here at UCSC. The medium-term perspective also needs to be complemented by understandings of the contemporary moment that bring a speculative approach to concepts like immigration and assimilation; my colleague Cat Ramírez’s Assimilation: An Alternative History is a powerful example.

“The Colombo ex frigata and Imagining Contact Beyond Conquest” is part of The Humanities Institute’s 2022 Imagination Series. This series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti in the Humanities community at UC Santa Cruz – each of whom highlight connections between imagination and their work or consider the role of imagination in fashioning new worlds. Throughout Spring quarter, be sure to look for these amazing essays in our weekly newsletter!