Grad Profile: Steven Green

Steven Green is a PhD candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. Green’s research investigates the role of foodways in shaping Jewish communities and culture in the American Midwest in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Steven Green is a PhD candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. Green’s research investigates the role of foodways in shaping Jewish communities and culture in the American Midwest in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

At the end of Summer 2022, we learned more about Green’s dissertation project. Green received a THI Summer Dissertation Fellowship in 2022 to support his dissertation work. We discussed Green’s novel approach to the question of Jewish community formation and the unique history of the Midwest, where food became a cornerstone of communal bonds.

Hi Steven! I hope your summer is going well. We appreciate you taking the time to talk to us a little bit about your ongoing research. Can you give us a brief description of your dissertation project?

Thank you for having me! My dissertation explores the various roles that foodways played in the construction and upkeep of Jewish communities across the midwestern states of Minnesota, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Iowa in the late-nineteenth and twentieth-centuries. Taking a few communities in each state as chapter case studies, I argue that foodways–through entrepreneurship, in the private home, and as an integral part of charity–were critical to developing Jewish communities. While most historical understandings of American Jewish communities often revolve around traditional Jewish institutions such as the synagogue or fraternal societies, I argue that food was just as important in the process of constructing and maintaining midwestern Jewish communities.

Very interesting! What is it like to study food through the archive? What types of records and documents do you use to study food?

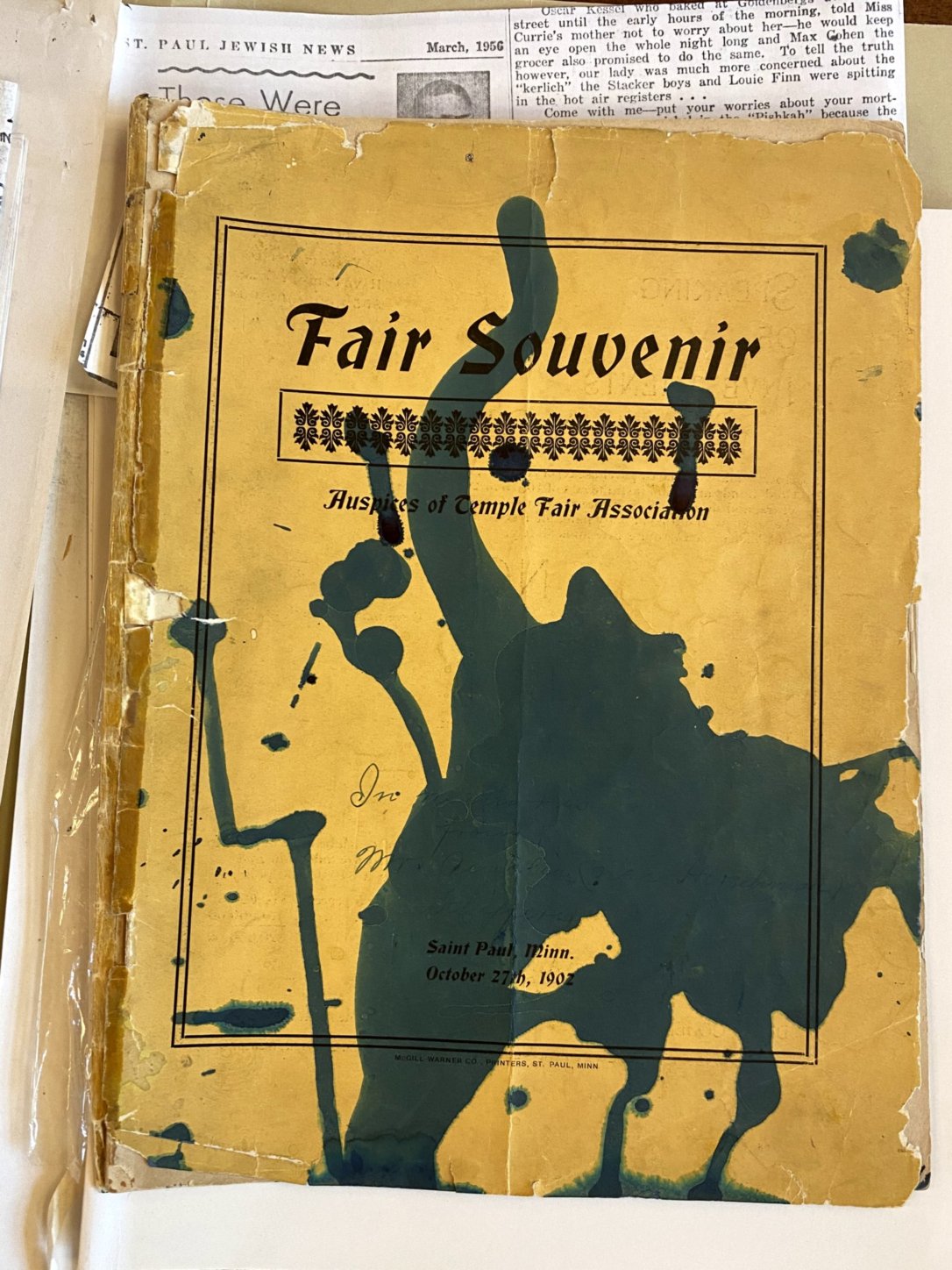

The instances of food that I look for are rarely the focus of specific collections, or even single documents, within the archive. This makes it much more tedious to search them out. The collections that my dissertation relies on are thus varied and wide-reaching; autobiographies, organizational records, oral histories, informal community histories, synagogue records, women’s diaries/journals, business directories, newspapers, and cookbooks all provide snapshots of the importance of food to the process of community-building. Within these, except of course for the cookbooks, food is never the sole focus. Rather, they show up in fleeting moments. It might be a brief mention of a North Dakota Jewish homesteader’s wife recalling how she had to prepare the traditional Sabbath dinner without proper or familiar Jewish ingredients, or a newspaper account of a Jewish organizational fund-raising dinner that featured various traditional Jewish foods that was attended by both the Jewish and wider non-Jewish community. But it is in these moments that we can begin to understand that food was the very basis of community in these Jewish communities across the Midwest. It is in these brief flashes within the sources that point to the larger power of food in Jewish communal development.

Why is food such a powerful and illustrative lens through which to understand the historical experience of Jewish communities in the Midwest?

To me, food is so important in understanding the experiences of Jewish communities across the Midwest precisely because it permeated the very fabric of communal life on so many levels.

To me, food is so important in understanding the experiences of Jewish communities across the Midwest precisely because it permeated the very fabric of communal life on so many levels. Food, because we engage with it on a daily basis, allows a much more intimate lens than traditional focuses of communal histories have allowed us. It is also something that, in looking over archival materials and other sources, that women and men discuss with such reverence and joy. In many cases, autobiographical accounts or contemporary journals kept by Jews detail food in incredible detail, often describing the cooking process, smells, tastes, and other sensory details that make food come alive. It truly is unlike any other lens through which to discuss history.

Another way that food helps illustrate a different story is because it also helps us to complicate the notion of what a community is. In many places I look at, a traditional “community” often did not exist; the physical spaces, such as a synagogue or Jewish community center, were not there. Rather, it was a collection of Jewish families, interspersed with other non-Jewish families, that bound together through a shared identity that often revolved around the consumption, preparation, and constant negotiation of foodways.

It also complicates the routinely masculinized understanding of communal development. Because women were often the harbinger of food in the Jewish household during this time period, they exercised their power this way. Thus, while my dissertation is first and foremost a story about the entangled nature of foodways and communal development, it is also an exploration into the powerful roles that Jewish women held in this process; it treats women as integral to the forging of communities.

How did Jewish foodways help the Jewish community build bonds across different ethnic and religious groups in Midwestern states like Minnesota and Iowa? Were there also times that Jewish culinary practices worked in the opposite way to isolate Jewish people and make them seem foreign and unassimilable? We’d love any examples you may have!

One of the overall claims that my dissertation seeks to prove is that the Midwest operated differently from other areas of Jewish settlement, particularly in large urban areas that have traditionally been the focus of Jewish communal studies such as New York or Chicago. By this, I mean that food could provide the cornerstone of communal gathering, belonging, identity, and cultural sharing that helped stabilize these communities. There was constant sharing of food between Jews of different denominations (Orthodox, Reform, Conservative), and between Jews and non-Jews, especially in some of the areas that I investigate. Charitable events such as fairs and donor luncheons held by Jewish women’s auxiliary organizations, for instance, were often a highlight of the yearly social calendar in midwestern cities, allowing Jews and non-Jews to purchase and consume typically Jewish foods while raising money for the Jewish community.

Of course, even when non-Jews did participate in the culinary traditions of Jews, there was typically a feeling of mystery. While many areas of Jewish development in the Midwest did not display the levels of anti-Semitism seen in urban areas or other areas around the U.S., non-Jews were sometimes wary of the seemingly “exotic” ingredients or preparation of unfamiliar foods and dishes. However, it typically did not lead to a feeling of isolation; rather, they were eager to take part. Many Jews were often seen as important figures across these midwestern communities, and the participation in Jewish fundraising events were routinely encouraged in the non-Jewish press. While larger cities in the Midwest, such as Minneapolis, had somewhat insular Jewish communities, in many cases Jews were among the first arrivals in cities and towns across the Midwest, negating this feeling of isolation and anti-Semitism. This, in turn, allowed food to permeate cultural and religious boundaries.

One of the things that people love most about food is its ability to fuse different cooking techniques and knowledges together to produce new and exciting dishes. Did Jewish cuisine blend with cooking traditions from other cultural groups to produce new foods in the period and places you study? What were these foods like?

This process of cultural sharing through foodways worked on many levels in the Jewish Midwest, especially during the time frame of my study. The agricultural variety and bounty of the Midwest often introduced new ingredients to the Jewish kitchen. On several occasions, women of various religious, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds got together to swap recipes, cooking and canning techniques, and knowledge of food preparation of unfamiliar ingredients. On a Jewish homestead in Willet, North Dakota, for instance, a Jewish woman learned various canning and preservation techniques from a Scandinavian Lutheran woman, who in turn supplied her with many recipes, including several lutefisk dishes. Because lutefisk is a whitefish dish, which many Jewish immigrants were familiar with, they tended to create hybrid dishes between lutefisk and gefilte fish, a common Eastern European Jewish dish. In this regard, not only did foodways constitute a cornerstone of Jewish communal development, but it also solidified and made possible inter- and intraethnic relationships in many of these areas.