Faculty Profile: E. Hande Tuna

Dr. E. Hande Tuna is Assistant Professor in the Philosophy Department and Affiliate Faculty in the Feminist Studies Department at UC Santa Cruz. They are a 2022-2023 Faculty Research Fellow and served as a Faculty Mentor for THI’s Questions That Matter Teaching Program on the theme of Imagination. Dr. Tuna is currently working on a book on imaginative resistance as well as publishing a series of articles from their Sensitive Aesthetics project. This summer, we spoke with Dr. Tuna about their contextualist theory of aesthetic normativity, the means by which our aesthetic perceptions can be “hijacked,” as well as their collaborative approach to teaching, mentorship, and community-building.

Dr. E. Hande Tuna is Assistant Professor in the Philosophy Department and Affiliate Faculty in the Feminist Studies Department at UC Santa Cruz. They are a 2022-2023 Faculty Research Fellow and served as a Faculty Mentor for THI’s Questions That Matter Teaching Program on the theme of Imagination. Dr. Tuna is currently working on a book on imaginative resistance as well as publishing a series of articles from their Sensitive Aesthetics project. This summer, we spoke with Dr. Tuna about their contextualist theory of aesthetic normativity, the means by which our aesthetic perceptions can be “hijacked,” as well as their collaborative approach to teaching, mentorship, and community-building.

Hello Professor Tuna! Thanks for chatting with us about your research and all the wonderful humanities work you’ve been involved in. Congratulations again on being named a 2022-2023 THI Faculty Research Fellow! To begin, could you give us a brief synopsis of your book project, Sensitive Aesthetics?

I have transformed my project, Sensitive Aesthetics, into a series of articles instead of a book. This decision arose from the realization that I needed to write a separate book on another topic I have been working on for some time, namely the phenomenon known as imaginative resistance. It made more sense to compile the articles I had on that issue into a book rather than publishing them individually. I am delighted to announce that this book is now under contract with Oxford University Press.

I investigate cases where our aesthetic perception is hijacked by our background cognitive states and draw lessons on how we should conduct ourselves in the realm of aesthetics.

Regarding the Sensitive Aesthetics project, let me provide a brief overview. In this project, I have developed a contextualist theory of aesthetic engagement and normativity, drawing insights from my analysis of aesthetic perception. Aesthetic perception refers to conscious experience of lower-level and higher-level aesthetically relevant properties of objects (e.g., properties of having a certain color, shape, being elegant, garish, vivid, etc.) through the five senses. What makes these properties aesthetically relevant is that they inform aesthetic practices, such as appreciation, curation, collecting, and critiquing. I analyze cases where our aesthetic perception, and the aesthetic practices it informs, go awry due to bad influences stemming from our prior outlooks (our expertise, beliefs, desires, fears, preferences, and attitudes) and use this analysis to ground a new account of aesthetic engagement and normativity. In other words, I investigate cases where our aesthetic perception is hijacked by our background cognitive states and draw lessons on how we should conduct ourselves in the realm of aesthetics.

One of the articles stemming from this project will be published soon. Titled “Apt Perception, Aesthetic Engagement, and Curatorial Practices,” it is co-authored with Octavian Ion, a Toronto artist specializing in abstract portraiture. In this paper, we delve into the practical implications of my contextualist theory of aesthetic normativity and engagement for curatorial and exhibition practices.

What is your favorite historical example of “hijacked aesthetic perception” that you explore in your work?

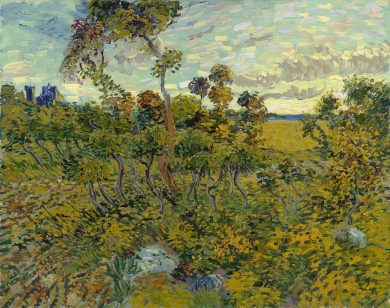

My favorite example is from a century ago. In 1908, Christian Nicholai Mustad, a Norwegian factory owner, purchased a painting by Vincent Van Gogh, following the recommendation of Jens Thiis. The painting is called ‘Sunset at Montmajour.’ It is a beautiful oil painting, comparable to ‘The Sunflowers’ or ‘The Bedroom,’ all of which were painted around the same time by Vincent Van Gogh. Mustad displayed it with pride as the centerpiece of his home until a dinner guest, the Norwegian consul in Paris, Auguste Pellerin, who was also an entrepreneur and a direct competitor of Mustad’s, as well as a collector of some repute, raised doubts about its authenticity. Once the center of attention, Van Gogh’s masterpiece was discarded in an attic and forgotten. You would think that at the very least he could have placed it in the bathroom or something, but he threw it in the attic. In 2013, the painting was rediscovered and authenticated. What is interesting about this story for me is the shift in Mustad’s perception of ‘Sunset at Montmajour’ that occurred after the question pertaining to its authenticity was raised. His perception of the properties of the painting changed: the wild, thick brush strokes no longer looked wild or unruly but studied, the warm yellows no longer seemed expressive but hollow, and the painting no longer struck him as beautiful. I believe Mustad’s perception is one of the many examples of hijacked aesthetic perception, and he is not aesthetically blameless.

In your context-sensitive theory of aesthetic normativity, the aim for aesthetic engagement is avoidance of bias, rather than “accuracy.” I’m curious how this theory plays out in your own experiences as a perceiver of aesthetic objects. Have you ever experienced an incidence of “hijacked aesthetic perception?”

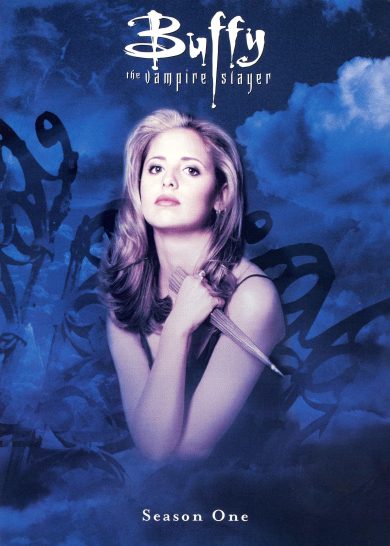

Certainly, I have experienced instances of “hijacked aesthetic perception” many times, particularly during my younger years when I was quite snobbish in my artistic preferences. Looking back, it’s rather cringe-worthy to recall. I used to dismiss anything that appeared on a best-seller list or any blockbuster film. However, over time, my perspective underwent a significant shift. I realized the absurdity of comparing, for instance, Buffy the Vampire Slayer to the Sistine Chapel, although I must admit that even during my snobbish phase, Buffy held a special place in my heart. My notions of lowbrow and highbrow art underwent a complete transformation. I now believe that each artwork should be assessed within its own category, as it would be unfair to do otherwise (my doctoral work touches on this a little actually). So, even if my suspicions that the next Marvel movie will be similar to its predecessors and lack aesthetic novelty are not entirely unfounded, this doesn’t mean that watching it wouldn’t provide a worthwhile aesthetic experience. In a way, I am correct in my assessment, but I am not truly engaging with the work itself due to my biases. Instead, I set it aside and watch another film, let’s say The Quiet Girl, which does offer a meaningful aesthetic experience. However, that doesn’t absolve me of aesthetic blameworthiness.

In 2021-2022, you served as a Faculty mentor for the THI Questions That Matter Course on Imagination. What drew you to this role? What is your approach to collaborative pedagogical mentorship and why is it important to offer graduate students these kinds of opportunities?

It was a great privilege to serve as a Faculty mentor for the THI Questions That Matter Course on Imagination. The invitation to join the group came from Nathaniel Deutsch, and I was immediately drawn to the role due to my work on the philosophy of imagination. I saw it as an excellent opportunity to assist students from diverse disciplines in coming together to create a course centered around this fascinating topic.

By collaborating and leveraging our collective strengths, we can enhance our abilities to think, imagine, and even feel.

My approach to collaborative pedagogical mentorship stems from my belief in collectivity. I am convinced that as individual thinkers and imaginers, we have limitations. By collaborating and leveraging our collective strengths, we can enhance our abilities to think, imagine, and even feel. This principle extends to teaching as well. When we come together, pooling our different expertise and experiences, we have the potential to create and deliver better courses.

It is vital to offer graduate students these types of collective opportunities for several reasons. First, by working collaboratively to develop and teach a course, they gain valuable experience in collective decision-making and syllabus creation. These skills will undoubtedly prove beneficial as they progress in their careers and potentially develop their own courses in the future.

Additionally, engaging in collaborative pedagogical mentorship exposes graduate students to a wide range of perspectives. It encourages them to recognize that their own perspective is not the only valid one and that incorporating diverse viewpoints leads to richer educational experiences. Through this process, they learn the importance of negotiation and the value of incorporating multiple perspectives to create a comprehensive and inclusive learning environment.

In short, I believe these collective enterprises can significantly improve our teaching abilities, for all parties involved, the mentors and the mentees.

Can you tell us about one community/group you’ve been a part of at UCSC that has shaped your time here so far?

The community that has had a significant impact on my time at UCSC is primarily my department. I am grateful for the support and camaraderie of my colleagues; they have been truly wonderful. However, I must also mention the incredible student body at UCSC. Their passion and enthusiasm for philosophy have profoundly shaped my experience here. While I already have a deep love for my work as a professional philosopher, witnessing the genuine excitement and intellectual curiosity of my students adds an extra layer of inspiration. And I sometimes teach more obscure topics in philosophy, like early modern women philosophers’ writings. I didn’t really expect students to be so interested in them. But the reception from the students, especially our undergraduates, was heartwarming.

Banner Image: A portion of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, painted in fresco by Michelangelo, and considered a cornerstone work of High Renaissance art. Photograph by Calvin Craig.