Faculty Profile: Renée Fox

Dr. Renée Fox is Associate Professor in the Literature Department at UC Santa Cruz. She served as a 2022-2023 THI Faculty Public Humanities, Digital, and Community-Engaged Research Fellow; co-organized the 2023 Festival of Monsters; and is the co-Principal Investigator for the 2023-2024 “Technological Monsters” Research Cluster. This Winter, we had the chance to speak with Dr. Fox about the experience of co-curating the exhibit, “Werewolf Hunters, Jungle Queens, and Space Commandos: The Lost Worlds of Women Comic Artists,” at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, UCSC’s Center for Monster Studies‘ recent 2023 Festival of Monsters, and how paying attention to cultural discourses of monstrosity might open possibilities for empathetic resistance.

Dr. Renée Fox is Associate Professor in the Literature Department at UC Santa Cruz. She served as a 2022-2023 THI Faculty Public Humanities, Digital, and Community-Engaged Research Fellow; co-organized the 2023 Festival of Monsters; and is the co-Principal Investigator for the 2023-2024 “Technological Monsters” Research Cluster. This Winter, we had the chance to speak with Dr. Fox about the experience of co-curating the exhibit, “Werewolf Hunters, Jungle Queens, and Space Commandos: The Lost Worlds of Women Comic Artists,” at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, UCSC’s Center for Monster Studies‘ recent 2023 Festival of Monsters, and how paying attention to cultural discourses of monstrosity might open possibilities for empathetic resistance.

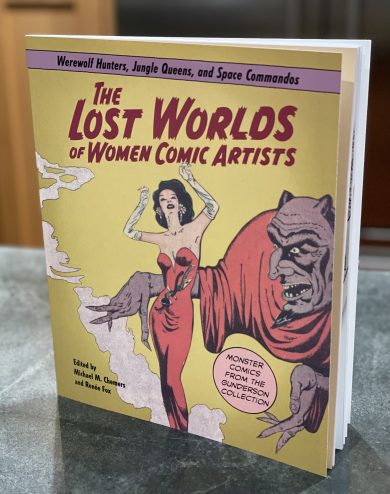

Hello Professor Fox! Thanks for chatting with us about your research and all the wonderful humanities work you’ve been involved in. Congratulations again on being named a 2022-2023 THI Faculty Public Humanities, Digital, and Community-Engaged Research Fellow! Your project involved producing an exhibit at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, “Werewolf Hunters, Jungle Queens, and Space Commandos: The Lost Worlds of Women Comic Artists,” which opened in October. Could you share a bit about your vision for the exhibition, and why you wanted to put it on at the MAH?

The exhibition was a deeply collaborative project and emerged organically out of conversations with Professor Michael Chemers in the Performance, Play, and Design department, and Jim Gunderson, an alum who has long been a great friend to the Humanities and Arts at UCSC. Jim is a massive collector of US comic books and original comics art, and in recent years has focused much of his collecting on women artists. He has also been very involved in the UCSC Center for Monster Studies, which Michael founded and we now co-direct, and he approached the Center about an exhibition that would combine our expertise in monsters with his collection’s strength in women comics artists. Michael and I were excited about the opportunity to think about monsters in (what was for us) a new medium, as well as to use this curatorial project as an opportunity to introduce UCSC undergraduates to public humanities work. Planning for the exhibition began in an Exhibiting Monsters course that Michael and I co-taught in Fall 22, where we spent the quarter working with a small group of students to research the comics that would be in the exhibition and develop ideas about how to frame this research for a specifically popular audience. The MAH was an amazing collaborator with us throughout the course, the subsequent planning, and the design of the exhibition–there is no better, more generous venue for exhibitions that involve the UCSC and Santa Cruz community.

As it evolved, the exhibition came to explore how American women comics artists used monsters to explore the histories and futures of the US as its racial, gendered, and national politics shifted throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries. Working within the often gendered and racially biased conventions of the comics medium, artists like Lily Renée, Marie Severin, Fran Hopper, Marcia Snyder, and Jill Elgin pushed against the industry’s confining frames (both literal and figurative), creating aliens, unexpected octopuses, hybrid beasts, and other monstrous bogeymen that laid the groundwork for women to make—and be—monsters throughout the mainstream comics of the 20th century. From the women in the 1940s who stretch their high-heeled legs across page gutters to fight the monsters of a xenophobic post-war American imagination to the monstrous women of the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s who defy both gravity and gender norms with their skimpy costumes and badass powers, the exhibition explores how monsters and monstrosity became tools for women comics artists to negotiate questions of power, exclusion, censorship, and identity.

Was there something in the exhibit you were particularly excited to have on display?

The exhibition is full of amazing original art, including a few pieces from the 1940s by the artist Lily Renée, that let you get a glimpse of the thought process as an artist moves from idea to actual comic book. One particularly special inclusion is a series of undated sketches (c. early 1960s) of the Incredible Hulk, drawn by Marie Severin, as she was refashioning him from an indiscriminately destructive monster into a character with multifaceted interiority. We’ve blown up one of the sketches on the wall so you can really see Severin’s detailed drawing of his face, and the other full body sketches are in a case right next to it.

There’s also a corner of the exhibition devoted to contemporary comic book vampires that I’m particularly fond of, including unique drafts of the Buffy spin-off comic Spike that show the artist, Jenny Frison, debating how much humanity she wants Spike to have as he fights off (other) monsters.

The launch of the exhibition coincided with the 2023 Festival of Monsters, which you co-organized (and for which THI was proud to be a co-sponsor). Congratulations on such a wonderfully rich event! I wonder if you could share a favorite memory from the festival. Was there a moment of community, learning, or surprise that stands out to you?

My favorite thing about the Festival was that it was an entire weekend of community, not just individual moments of it, and that the community was forged between UCSC folks, monster-loving people from across Santa Cruz and the Bay Area, and interdisciplinary scholars who came from across the world. There were sessions that I felt particularly excited by, like the panel of comics artists who produced the queer horror comics anthology Theater of Terror and the discussion with Black Nerds Create, but what especially stands out is the Monsters’ Ball that we hosted at the Institute for Arts and Sciences on the Saturday of the Festival. It was amazing to see all of these people we’d been thinking so intensely with over the last two days all show up in the monster costumes they’d carefully traveled across the country (or world) with and dance the night away.

The festival aimed to explore “the ways monsters and tropes of monstrosity both preserve and conflict with forms of social and cultural injustice.” Can you say a bit more about the cultural and rhetorical role of “monstrosity” as a concept that still shapes issues of injustice?

In an NPR story on the role of university communities in confronting the atrocities unfolding in the Middle East, Princeton Professor Eddie S. Glaude described his own sense of compassionate responsibility using the language of monstrosity: Every dying child, he said, is “just as valuable, just as innocent, just as cherished” as every other dying child, and “you can become the monsters that you despise, if you lose sight of that.” As humanists, our role is to “bear witness to the conditions under which human beings can become monstrous, [and to do] that without hesitation or fear.” Monster studies explores how cultural discourses of monstrosity enable us to bear witness to atrocity and social injustice, and by such witnessing to envision empathetic forms of resistance and a more just future for everyone.

Monster studies explores how cultural discourses of monstrosity enable us to bear witness to atrocity and social injustice, and by such witnessing to envision empathetic forms of resistance and a more just future for everyone.

In times of accelerating oppression, racism, and border policing, monsters proliferate in popular culture: as defamiliarizations, as metaphors, as scapegoats, as illicit temptations, and as invasive species that fundamentally shift how we understand definitions of humanity, belonging, and exclusion. Dracula turns to mist and creeps in through the tiniest cracks, even when no one quite remembers inviting him in; Little Red Riding Hood turns out to be a werewolf in disguise, skipping over granny’s threshold as though she belongs; Godzilla bursts ashore only to confront even more terrifying creatures that want to obliterate the city he ends up both protecting and leveling. Monsters are scary not because they are easily recognizable and definable “others,” but because they are designed to reveal our own complicity in their creation: they are the return of all we’ve tried to eject, they are us as much as they are not us, they are our misguided prejudices recurring in new and ever more destructive forms. Monsters are borne from ideologies of injustice and exclusion even if they themselves aren’t always—aren’t even usually—the ones who are unjust or inhospitable, and the goal of the Center for Monster Studies and the field of Monster Studies more widely is to discover how monsters produce, illuminate, and subvert political and cultural discourses of intolerance.

This year, you are also the co-Principal Investigator for the “Technological Monsters” Research Cluster, which comprises a group of faculty from the humanities, the arts, social sciences, and engineering, to explore what monsters may have to teach us about humanity in an ever shifting technological landscape. Why is it important for you to engage in this kind of interdisciplinary research collaboration? What’s one question this cluster aims to explore that you find particularly stirring in our current moment?

Monsters are intrinsically interdisciplinary. We find them in global literature, performance, arts, games, and all kinds of media, and they emerge in relation to new technologies, scientific development, social change, and planetary catastrophe. The premise of this cluster is that bringing different disciplinary expertise to bear on studying monsters will open new paths to understanding how they embody the cultural anxieties and affordances intrinsic to technological development. From nineteenth-century novels like Frankenstein and Dracula, in which complex monsters are products of and metaphors for technological advancement, through early twentieth-century films like King Kong and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms that use classic monsters to show off new moving picture technologies, to sci-fi blockbusters like Battlestar Galactica and Ex Machina that make the indistinguishability between artificial intelligence and humanity its own uniquely monstrous phenomenon, monsters have long been expressions of the possibilities and dangerous limitations of technological advancement. In this respect, the study of monsters provides opportunities to explore the junctures between technology and the imagination, often transhistorically and transnationally, as the same old monsters are reproduced in new times, places, and media, to vastly different ends.

At the same time, the cluster asks how we can see monsters as more than simply reactionary phenomena, created in response to real or imagined technological crises and reflecting societal misgivings about the transformations technology might effect on human experience. At a moment when so many factions are questioning the value of the humanities, we aim to explore what cultural productions like monsters actually do, in and to the world. How can creating monsters produce, enhance, and synthesize technologies that become integral to media and the larger world? What do we learn by seeing monsters themselves as a form of technē, an art of development that, as Jeffrey Jerome Cohen writes in his foundational essay, “Monster Theory: Seven Theses,” “enables the formation of all kinds of identities”? That is, this cluster is interested in discovering the generative capacity of monsters as well as their facility as cultural mirrors. We hope the cluster—including, as it does, not only those of us whose technological knowledge peaks with Dracula’s vampiric typewriting in 1897, but also those of us who work on the cutting edge of contemporary game mechanics, digital storytelling media, and virtual reality—will generate new ways of “thinking with” the monster across time, space, culture, and technology.

Think less in terms of bringing our scholarship to a non-academic audience or using our scholarship on behalf of other communities and more in terms of how our skills and objects of study can work in tandem with other kinds of expertise to produce truly collaborative projects, experiences, and ideas.

Much of your work–the MAH exhibit, the Technological Monsters Cluster, your co-founding of the Center for Monster Studies–aims to extend intellectual labor beyond the academy, and create connections in the broader community. What advice would you give to other humanities scholars who are interested in amplifying the “public” dimensions of their research, writing, and academic community?

My interest in public-facing and community-engaged scholarship began with my work as co-director of the Dickens Project, which has been bringing scholars and members of the wider public together to think collectively about 19th-century literature for over 40 years. The advice I’d give to other humanities scholars is to focus on what kinds of new conversations and knowledge might emerge from widening our communities beyond academia—to think less in terms of bringing our scholarship to a non-academic audience or using our scholarship on behalf of other communities and more in terms of how our skills and objects of study can work in tandem with other kinds of expertise to produce truly collaborative projects, experiences, and ideas.

Banner Image: Photograph from the 2023 Dickens Universe, which took place at UCSC from July 22-29, 2023. This panel was a wrap-up discussion about A Tale of Two Cities on July 28 at Stevenson Event Center. Panel featured, from left to right, Literature Professor Renée Fox (UCSC), Professor Andrew Miller (English, Johns Hopkins University), Professor Catherine Robson (English, NYU), Professor Logan Browning (English, Rice University), Professor Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkley), and Dr, Christian Lehmann (Bard Early College High School).