A Deep Read interview. Percival Everett and the making of James

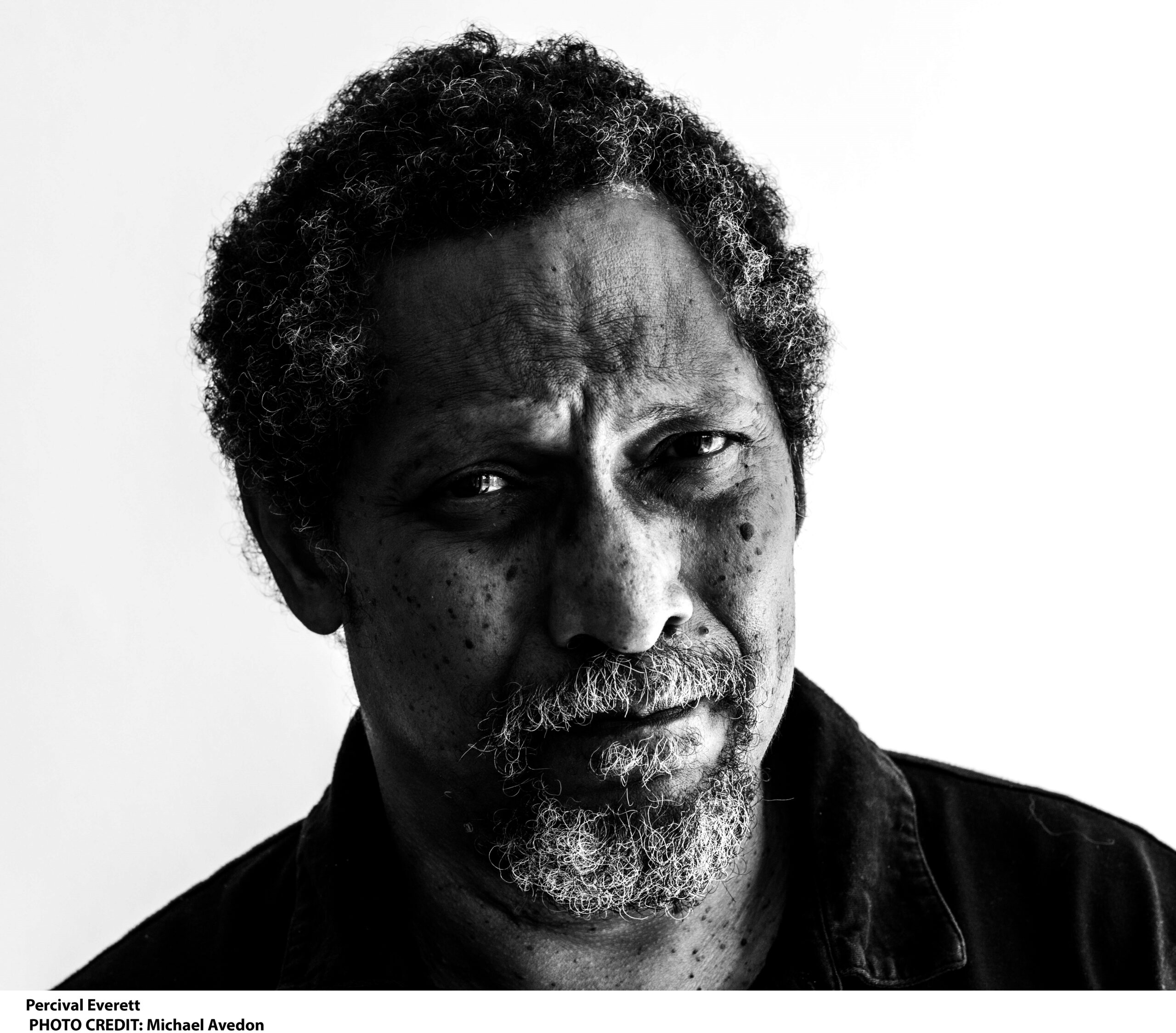

This spring, Percival Everett spoke with Dan White, Humanities Writer at UC Santa Cruz, about the creation of his 2024 National Book Award-winning novel James, a book that reoccupies and reimagines Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of the enslaved character Jim.

James is this year’s UC Santa Cruz Deep Read book. The Deep Read is a free public program at The Humanities Institute that creates a reading community around an award-winning book. The program includes an email series, a course, virtual and in-person discussions about the book with faculty members from different disciplines, and a culminating event with the author in Santa Cruz. On May 4, Everett will be in conversation with Deep Read Faculty Co-Lead and Professor of Literature Vilashini Cooppan at the Quarry Amphitheater.

In anticipation of his visit to UC Santa Cruz, Everett talked with White about his writing. During a wide-ranging, informal talk, Everett delved into his ongoing conversation with the works of long-dead authors, his adventures as a screenwriter, and why he refuses to write novels with obvious take-away messages for the reader.

By Dan White

DW: Where am I reaching you from?

PE: I’m in my studio. My painting studio is a few blocks away. This is where I write, but mainly I repair guitars and mandolins. This is where I do that… I started doing it during COVID because I could find broken guitars for 18 dollars and end up having a nice Gibson L or something. And then all of a sudden, I had too many guitars, and other people started discovering this hobby, and now broken guitars cost 200, 300 dollars plus. (laughs.)

DW: Kind of reminds me of Daniel Day-Lewis taking a year off to cobble shoes.

PE: Well, that sounds like a great idea. A new hobby for me.

DW: And I read somewhere that you train horses. Surely all these experiences make their way into your art in some way.

PE: I don’t train horses now. Now I am just trained by my two dogs. But I think everything I learn from making art comes from animals.

DW: Yes. Animals have such a powerful sense of presence. They live in an eternal now.

PE: A horse has never lied to me.

DW: In a couple of interviews, you’ve mentioned being in conversation with Mark Twain while writing James. From a craft perspective, what does that actually mean? What does it feel like to engage in a dialogue with another writer—especially one from a different time—while you’re in the process of creating your own work?

PE: First of all, I am very lucky that I get to participate in this ongoing discourse that is, well, I hesitate to say storytelling but constructing meaning, even though as a writer I don’t get to make any of it but I get to present it so meaning can be made from the product. I was one of Kurt Vonnegut’s army of 14-year-olds when I was a kid. You know, I couldn’t wait for his new books to come out. Even though I don’t write anything like Vonnegut, I can see his influence on me and the way he responded to the world and saw the world and the generosity of spirit that he seemed to always exhibit regarding art. That not only influences me but keeps me writing and thinking about those things as I do it—or I should say when I’m away from it—because I don’t think of anything when I’m writing. I don’t know if that made any sense at all.

DW: Well, that makes a lot of sense because writing is such a private act for you. You shut the world out.

PE: Well, I don’t like messages so I abandon all allegiance to my own beliefs knowing that I can’t escape them. My politics will be there but if I think about politics when I am writing I am doomed to write a message novel and I am not interested in doing that.

DW: So these themes kind of appear organically in your work – or is it that you can’t keep them out?

PE: We can’t keep them out. The things that are important to us will show up. Mainly, I always have some very abstract and logical or even arithmetical axiom or idea at the bottom of my work that I am trying to work out that I don’t expect any reader to see, and in exploring that I start trying to find stories that will allow me to think about that in different ways and the stories are—often there is no way to connect them but they connect for me.

DW: Did writing James—which in many ways is a very straightforward story—feel different to you from writing some of the other novels where the philosophy is more front and center, and in which the reading experience is more challenging—an enjoyable thicket for the reader to push through? I’m thinking of books like Dr. No and Glyph, for instance.

PE: Certainly it was, in that I was dealing with an extant text, and also the research was different. My research for writing James was more or less forgetting another text, not exploring it. I tried to create a blur. I didn’t want to remember any of the words that Twain used but I wanted to remember the world, so when I finished my exercise of finding a way to hate it, I closed Huck Finn and still have never looked at it since I started writing James. And anything that is in James comes from my memory of that world, not from any appeal to the text.

DW: I’d heard that you read Huck Finn many times in preparation for this …

PE: Yeah, just so I could really get sick of it. You know how when you say a word over and over and it starts to feel weird and lose meaning? It was the same thing—after the tenth reading, it was just nonsense.

DW: But now there is a tremendous amount of public fascination with Huckleberry Finn—a newly rekindled discussion because of the success of James. And I know you like to move on to the next thing, to move on to the next work instead of dwelling on anything you’ve written before. Has that been a challenge for you, to linger on James for this long?

PE: Well, I still work. It is just a matter of compartmentalizing. It is great that people have this interest in this book, but my interest in it was gone as soon as I finished. People will point out things that I never thought of, which is why I’m writing in the first place… but I am thoroughly sick of James.

DW: I figured you might be, but I bet you’re getting contacted by much younger readers now—by high school students, perhaps for the first time.

PE: Certainly I am. My other works are—I don’t think people discover them until later anyway. But this one is more accessible for everyone. (But) the increase in mail has actually come from white people over 60 and 70. Every day. And they identify themselves: “I am a white woman. Eighty years old!” Things like that. Just tons of that kind of mail. It is interesting. It is very sweet. You know, I would be excited if any book were getting this kind of attention—a literary novel. It is great that it happens to be mine, it is wonderful, but I am just encouraged by the fact that a novel is getting this kind of attention. That is thrilling to me. I would feel really positive if anyone’s book was getting that kind of attention. I just happened to wander into this kind of attention. I’m not sure if it’s deserved or whether that even needs to be part of the discussion, but it’s a nice thing.

DW: You’re also in this highly public event—the Deep Read at UC Santa Cruz—and soon you’ll face a whole amphitheater full of people who have been reading along. You talk a lot about writing being a deeply private and subversive thing—you can’t really keep your reader in mind when you work—so what is it like to be involved in a program in which you will see 2,000 of your closest readers right in front of you in a big amphitheater?

PE: It’s fun. People see stuff I don’t see. And I always confess that I suffer from work amnesia—people will bring up scenes that I don’t remember. I’ll have to do some work in my head to get back there. But that is not a bad problem to have. I feel pretty fortunate about that.

DW: Do you ever look back on your large body of work—where they are all so different—and think about how the books interconnect? How is it that you came to write James at this juncture of your career? Is it perhaps something you could not have written before? Do you think about where it exists in the pantheon—could you not have written it before?

PE: I see all the works as in conversation with—except for my first novel (Suder, 1983). I don’t know how to fit that into a larger conversation. And it takes me a few books to work through different ideas. But if I had written James ten years ago, obviously it would’ve been a different novel. Who knows.

DW: You’ve written so many different kinds of books. Your works seem to come from different aspects of your creative persona. If I was your agent or publisher, I would be begging for James the sequel after the huge success of this. Does it make you want to run the other way and write something else, like Glyph? Or how does it impact you?

PE: The attention doesn’t affect me at all. Again, it’s nice. It’s like one day finally I might wear a shirt that everybody likes and it’s: “Hey, nice shirt.” And then it’s in the wash.

DW. And there’s nothing you can do once it’s in that washing machine.

PE: Yes. Nothing you can do about it. I write because I am interested in different things in the world. I’ve never written something hoping that it would “hit” or be popular. And the same is true with the novel that’s following this one. It is something else. It’s something different. And now, as I’m older—for the first time in the last few years (when I’ve already been old for a while now)—it has dawned on me that I have a limited amount of time to make the books I might like to make. So it’s even more crucial for me now that I choose things that are artistically and philosophically interesting to me—and not go on any kind of success.

DW: Could you talk a little bit about your work in progress?

PE: No. I generally don’t talk about it… it’s a novel. But you probably could have guessed that. As I always say — if I could encapsulate it, I would have written a pamphlet, not a novel.

DW: Any challenge you still want to take on? In the past you’ve talked about your desire to write a purely abstract novel.

PE: Well, I am always trying to make things shorter. I am still trying to make an abstract work. The difficulty for writers is that the constituent parts of our art are representational. Unlike a note of music or paint, they necessarily tie to concepts and things in the world. So the idea of making that abstract is confusing in itself. I think I should be able to do it. I’ve never seen it. I don’t know what it would look like. I may not even know if I’ve achieved it—if I ever do it—because someone else could say that. “Oh, he managed to do it before that bus hit him.” It’s always in my head. And novels take different shapes.

DW: You’re also a mentor, a teacher. You teach grad students one-on-one, and you teach undergrads. How do you run your classes?

PE: I actually prefer teaching undergrads. They are more adventurous than grad students. My job with graduate students is to disabuse them of the idea that there is a correct way to make a novel—to get them out of whatever rut they’ve found themselves in, just trying to do something “right.” And I find undergraduates are a lot more open. And often, the work is not as good—not as polished—but it can be a lot more fun. I don’t think there is an interesting work in the world that is not a failed path. That is often what’s interesting—fascinating—about literature: when does a story fail? And that’s not a bad thing.

DW: So you are saying successful work will originate from something that was originally considered a failure?

PE: No. I think all great novels fail in some way. And that is what makes them interesting. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—it’s not a very good novel when you get right down to it—but it’s really important for a number of good reasons. So art’s an interesting thing. I read everything because I often learn from stuff I wouldn’t normally read or that I don’t even like.

DW: How does Huckleberry Finn fail?

PE: Twain abandoned the work for several years in the middle, and you can almost see the demarcation—the language changes, the movement of the novel changes. He abandons Huck’s moral dilemma to some extent to move on to an adventure with the reassertion of Tom Sawyer. And that’s sad to say—and I try to find ways to reason where it’s not the case—it is a mercenary move on his part to reintroduce this moneymaking character, Tom Sawyer, Twain having been quite famously in debt all the time. So it does fall apart—and because of the character I actually hate: it’s Tom Sawyer.

I did find a way to read it more generously, I guess you could say—with more generosity to Twain—and that is: Twain, being a decent person in many ways (I’ll say something else about that in a second), did not like the way Reconstruction had affected the South, and particularly newly freed slaves. And one of the things that Tom and Huck are doing is using Jim as a pawn in a game—very much as newly freed Black people were in the North and South. And that could be—even if it’s unconscious—and it doesn’t matter what he meant—but that’s a way of reading the text in a more generous way.

There’s a woman, Kerry Driscoll, who wrote a fantastic book (Mark Twain Among The Indians And Other Indigenous Peoples) about Twain’s treatment of Native people in his writing. And you come away from it not feeling terribly positive about Twain. He really hated—he was a bigot when it came to Native people. And I came to that just recently. So I am reassessing my reevaluation of Twain vis-a-vis African Americans as well. That’s just how he was in the world.

I, of course, am trying to be respectful of the fact that I am benefiting from 140 more years of human so-called evolution. But I’m wondering: if you can’t see your racism towards anyone and then own up to the fact that you can behave in a racist way—then you can never honestly address it. So I am wondering—being a product of his time—much of his attitude towards Black people was paternal, which was, at its root, racist. Which is why Locke, Rousseau, and Voltaire are present in the novel.

DW: Speaking of Huckleberry Finn’s shortcomings—some of the issues that Twain kind of elided in the text—such as the fatherly role of James to Huck—you dove right in. How soon in the composition process did you know how much of a father figure that James would be to Huck? Did you know from the beginning?

PE: Yes. It’s present in Twain’s world also. But it is complicated by the fact that Twain’s depiction of Jim is so stereotypic—superstitious, simple-minded, and not subject to second-order thinking that might make him a more interesting character. But it occurred to me almost immediately—because it is there.

DW: Your fleshing-out of James as a father figure has been the subject of a broad conversation—and there’s also a fascination with way your book dramatizes this kind of code-switching, in which James will speak one way to other enslaved people and in a much different way to the white characters …

PE: Everyone wants to call that code-switching—I just call it being human. If you are surviving, language is the first survival skill we learn. And to give it a cool-sounding name (laughs) I think sometimes misses the point—that it is simply what we do. I am not going to start calling eating a “nutrition injection.”

DW: Well, it just feels like survival mode. James had to keep his learning and reading completely private. As you mention—as you say—the act of learning how to read could get you killed.

PE: Yeah. Apparently it still can.

DW: How so?

PE: Are you familiar with a state called Florida? (laughs.)

DW: Speaking of Florida, you’ve been very outspoken about book bans as performative acts—and attempts to censor literature.

PE: It is an act of fascists. That is the first thing fascists do—go after books and art—because that is where we are most human. Our consumption of those things. And it is not writing that I consider so wonderfully subversive. It is actually reading, the most subversive thing we can do. The second most subversive thing you can do is not writing. It is being part of a book club because you are really keeping art alive and talking about ideas and that is fantastic.

DW: So I suppose, in that context, The Humanities Institute’s Deep Read program must be incredibly subversive, considering that it’s like a gigantic book club.

PE: It is terrific. I go out and do these things now and speak to a bunch of people and I point out to them that we all think alike in that we love literature, but, in the mad scheme of things, this is not a very large group. My publisher sells 50,000 books, they’d be thrilled. But if I sold 50,000 records, I’d never record again! So we’re not a reading culture. We have to keep that in perspective. I wish we were more of one.

DW: Yes, and I just read that we are reading fewer books than ever before in US history.

PE: Which is crazy since there are so many more of us—because they are not making that figure per capita. (laughs)

DW: I just can’t understand why reading is not an intrinsic value for everyone.

PE: If I can write a novel that challenges TikTok, maybe we have a chance.

DW: And that poses a real challenge for you and all literary artists. In an age where people aren’t reading very much, is it still possible that art can make people better human beings, and lead to a better society?

PE: If I didn’t have that reason, I wouldn’t be making art at all. I truly hope that it’s possible—Walt Whitman in (By Blue Ontario’s Shores) said, and I paraphrase: if you want a better society, produce better people. And when I say art, I have an expansive idea of art. It is not just literature, it is not just painting and music. Scholarship is art. Journalism is art. These are things that affect us, and we should go at them with the understanding that we are creating our culture.That said—Picasso’s painting Guernica changed the world. But when you think about it, very few people have ever seen it.

DW: And you are a painter yourself. As with your novels, you are in complete control when you’re working on a canvas. But now you’re attached to write the screenplay for the movie version of James, making you part of a larger process, a bigger machine in which you’re just one component. What’s that like for you?

PE: Writing a screenplay is a very new experience. I’d have to get back to you on that. But so far, I’ve enjoyed the process. I’m talking to smart people and handing in work I don’t feel an attachment to. I want to make it a special work, but it’s not the same as making a novel, and I have no proprietary feelings about a film in the same way I would about a novel, because I understand it is a collaborative work. And I am not a filmmaker. I don’t have a vision of it. That’s for other people to come up with. And I’ll try to do my part in this, but it may well look very different from anything I’ve imagined, and I’m completely open to that.

DW: Because in a sense, you’ve already been through that with Erasure, which was adapted into a film, American Fiction. They had their vision.

PE: And I had nothing to do with the making of that film, except for just making some good friends. And I really liked the work. Even if I hadn’t, it’s an exciting thing to see a brand-new work of art generated by something that you’ve made.