Alumnus Profile: Isaac Blacksin

Dr. Isaac Blacksin is a graduate of the History of Consciousness Department at UC Santa Cruz. In 2019-2020, he was the recipient of THI’s Yearlong Dissertation Completion Fellowship. He is currently serving as a 2021–2023 Postdoctoral Fellow in Communication as part of the USC Society of Fellows in the Humanities. In March, we discussed Dr. Blacksin’s evolving research work, pedagogy, and the role that interdisciplinary thinking—and the humanities more generally—can play to uphold or challenge practices of gatekeeping and exploitative labor that can flourish in higher education.

Dr. Isaac Blacksin is a graduate of the History of Consciousness Department at UC Santa Cruz. In 2019-2020, he was the recipient of THI’s Yearlong Dissertation Completion Fellowship. He is currently serving as a 2021–2023 Postdoctoral Fellow in Communication as part of the USC Society of Fellows in the Humanities. In March, we discussed Dr. Blacksin’s evolving research work, pedagogy, and the role that interdisciplinary thinking—and the humanities more generally—can play to uphold or challenge practices of gatekeeping and exploitative labor that can flourish in higher education.

Hi Isaac! Thanks for chatting with us about completing your PhD, your ongoing research, and your current position. To begin, could you give us a general synopsis of your dissertation project?

Hi there. Thanks for inviting me to speak about my work. My dissertation explores the lived experience of armed conflict and its mass mediation. It asks how violence shapes – and is shaped by – news representations of war, and how journalists manage the twinned pressures of war and its narration. Based on years of ethnographic fieldwork in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon with journalists from the New York Times, Al Jazeera, NPR, and other international news organizations, the dissertation challenges dominant conceptions of war by revealing how representational authority comes to be. Analyzing the practice, language, and politics of war reportage, I show why news coverage of conflict, widely presumed to function as a critique of excessive violence, instead serves to sanction official rationales for war. I hoped to capture the limits of journalism in wartime and the possibilities entangled in war reportage for knowing war anew.

Your dissertation argues that how war becomes meaningful through journalism is critical for understanding and responding to violence in the world. What can journalistic production, and especially war reportage, teach us about the way we craft narratives and memories to sustain conceptions of the world?

War reportage both elicits and satisfies popular desires for a particular reality of war, a reality that centers the morality of militarism while mystifying its political logic. Journalistic focus on individual suffering, I argue, displaces attention to those systems that cause suffering, and the meaning of war in this way transforms from the effects of policy on populations to the effects of violence on the innocent. Narrative is the mechanism through which this transformation takes place. Narrative “makes the real desirable,” as Hayden White puts us, and it does this by imposing upon events the formal coherence of a story, a coherence that responds to and reproduces a normative order. The reality of warfare, as given in the news, appears to speak for itself by displaying a certain coherence – of victims and perpetrators, killing and saving, justified force and criminal violence – that “summons us from afar” (in White’s memorable phrase) in its articulation of what we are already primed to expect. Narrative in this way mystifies those things unsuited to a dominant conception of war – killing as saving, for example, law as criminal – and thereby unsuited to the coherence imposed as common sense. The task, as I see it, is to disassemble the coherence of war that journalistic narrative attempts to make total. The task is to challenge conventional meanings for war by understanding how particular they can be, and how authority is constituted through the narrative concealment of this particularity.

You are serving now as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the USC Society of Fellows in the Humanities. How has your research project evolved since you graduated? What are some of the questions driving your writing right now?

The dissertation is now a book under contract with Stanford University Press, titled Conflicted: Making News from Global War. And I’ve also been researching for two new projects. The first is an ethnographic study of the civilian body as a central but contingent figure in the imagination and activity of military conflict. Building on fieldwork conducted in Iraq, Afghanistan, and recently in Ukraine, this project tracks the way suffering civilians are forensically and ideologically positioned – in war crimes investigations, NGO fundraising, military targeting protocols – in order to interrogate the prominence of the civilian casualty as a site of empathy and vengeance. The second new project maps connections between warmaking and filmmaking, looking at how those who fight wars respond to cinematic representation, and how cinema both registers and transforms what war is imagined to be. From action-movie screenwriters tasked by the Pentagon to brainstorm speculative military scenarios, to combat veterans employed as consultants for Hollywood war films, to military “training villages” staffed by ethnic actors and special-effects artists that simulate the cultural conditions of warfighting, the enmeshment of war and cinema is strange and consequential. These new projects extend the questions posed in my dissertation: What do we know of war, what are the boundaries of this knowledge, and how are these boundaries policed or contested by those producing knowledge from war?

You graduated from UCSC’s History of Consciousness Department, and you are now a Postdoctoral Fellow in USC’s Communication Department. You have described your work as “operating at the convergence of cultural anthropology, political theory, and media studies.” Can you share a little bit about the importance of maintaining an interdisciplinary approach to your work and cultivating an interdisciplinary research and writing community, like the one at USC’s Society of Fellows?

A given discipline’s value – a value that may be questioned at moments of university austerity – can be enhanced through gatekeeping.

Interdisciplinarity is, I think, double-edged. On the one hand, it’s important – vital, even – for generative thinking to emerge on topics like violence and representation. Our disciplinary borders are in this way limits to transgress. On the other hand, interdisciplinarity seems, to me, professionally dangerous. While much lip service is now given to interdisciplinarity, departmental hiring decisions appear to reflect the prerogatives of disciplinary reproduction and the mandate to enforce disciplinary boundaries. A given discipline’s value – a value that may be questioned at moments of university austerity – can be enhanced through gatekeeping. Fantasies of the “life of the mind” here rub up against institution management. So while the cultivation of interdisciplinarity seems necessary for critical inquiry and creative analysis, the performance of interdisciplinarity – especially among those, like myself, without a certified disciplinary home – may be a risky business. How one negotiates this tension reflects intellectual priorities and professional status.

As part of your position, you teach three courses over your four semesters at USC. Can you tell us a little about these classes? How has your pedagogical practice evolved as you find yourself on a new campus and in a new teaching environment?

At USC, I’ve offered courses on the global media history of the War on Terror, on major theories of ideology and mass communication, and on theories of methods for making media that addresses social conflict. And my pedagogy, as you suggest, is changing to suit my circumstances. From UC Santa Cruz to USC, these circumstances include smaller classes, a more conservative institutional environment, and a more international student body with a distinct class background. Students at USC will ask questions I never received at UC Santa Cruz, questions like, “Why is empire bad?” It’s not a deficient question by any means; it’s a generative and complicated question. But it’s a question that expresses distinct circumstances, and which then requires pedagogical adjustment. I continue to learn not to presuppose students’ knowledge of any given topic – especially concerning 9/11 and the subsequent “anti-terror” wars – and I try to leverage students’ particular interests, and particular life experiences, to illuminate the issues under examination. What conflicts is a given student confronting, and how are these conflicts transformed through their representation? Starting there allows me to unfold my courses in ways that are more responsive and less predetermined.

As someone who has traversed disciplinary boundaries in their education, research work, teaching, and writing, why do you think the Humanities remain a fundamental and necessary part of education and society generally?

So when we say that the humanities are fundamental to education, we should be careful, I think, about what “education” means in any given instance, and the degree to which the humanities perpetuate those things they attempt to transform.

A cynical answer: They’re not, necessarily. Or rather, the things the humanities do can be fundamental, but not only that, because the humanities are also part of what they might seek to challenge. My worry is that a certain magical realism has taken hold, in which the social value of the humanities is seen as a protection against the declining state of higher education, or as a frictionless means to confront proliferating political, ecological, and social crises. This position abstracts the humanities from the conditions of their production in the university, where teaching labor is increasingly casualized, administration bloated, endowments financialized, tuitions increased, budgets cut. So when we say that the humanities are fundamental to education, we should be careful, I think, about what “education” means in any given instance, and the degree to which the humanities perpetuate those things they attempt to transform. This isn’t to say that the humanities cannot be fundamental to an educated polity and a just society. Rather, it’s to insist that asserting this fundamentality should not blind us to the humanities’ entanglement in systems that leverage humanities education for purposes neither educative nor just.

What is the space on UCSC’s campus that you miss the most and why?

A great question, thank you. I really just miss space most generally. The ability to walk a good distance through meadow and forest – out to Pogonip, up through North Campus to Twin Gates, across the Great Meadow and down to East Meadow (while it exists) – this is a real treasure for contemplation, for conversation, for companionship. It’s a rare thing to leave the classroom and immediately spread oneself onto this vast terrain. There are so many hidden gullies, unexpected turns, steep climbs, wide vistas. In this sense, walking the Santa Cruz campus is like the experience of thinking itself.

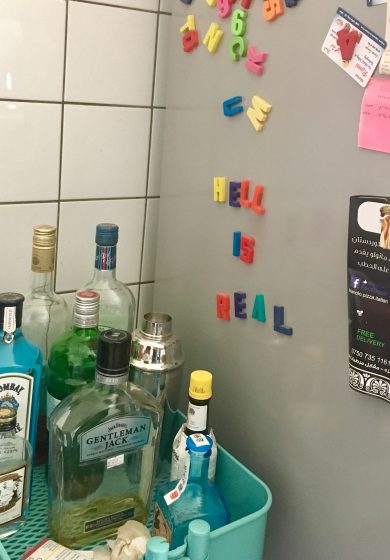

Banner Image: A café near Duhok, Iraq. Photograph by Isaac Blacksin.