Bearing witness to COVID at UC Santa Cruz

Someday, future historians will read the detailed stories of 22 UC Santa Cruz community members who lived through the COVID-19 pandemic.

There will be stories of empty-nest households suddenly refilling with returning children, telecommuting parents, and houses crammed with people getting on each other’s nerves but figuring out new ways to get along.

There will be tales of sudden changes to best-laid plans, each of them containing the words “and then COVID happened.”

These vivid firsthand accounts of fear, isolation, hopelessness, optimism, and frustration will ring truer than dry passages in an academic history book. They will read the story of Nicole Afolabi (College Nine ’21, politics and statistics) who thought about how hard it would be to describe the pandemic for future generations. What will it take to show them the scope of this?

“I don’t think you’d be able to imagine, honestly, the whole world just shutting down, and you couldn’t go anywhere, basically,” said Afolabi.

They will read the story of students finding themselves stranded in hometowns where their friends want to go out with them every night and think COVID is a hoax.

Collectively, those accounts will reveal the story of a year like no other, in which a pandemic, the threat of the devastating CZU August Lightning Complex fire, and the impact of the UC Santa Cruz graduate student labor strike converged, along with a resurgent national conversation about racism, with nationwide protests over the murder of George Floyd.

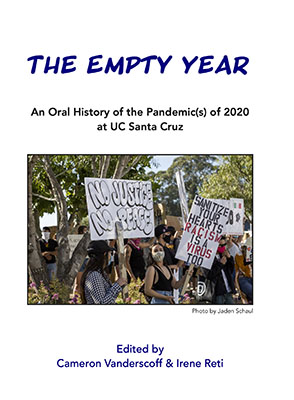

These stories of resilience and loss are preserved in The Empty Year: An Oral History of the Pandemic(s) of 2020 at UC Santa Cruz, an immersive project that includes a 540-page published book that will be available in mid-May with full-color images by Santa Cruz Sentinel photographer Shmuel Thaler and other photographers, and an online electronic version. The Empty Year collects oral histories that five UC Santa Cruz undergraduate and graduate student oral historians gathered last year under the guidance of the University Library’s Regional History Project.

The process was emotional for the interviewers as well as the subjects.

“While the pandemic can be mapped and tracked and tallied with numbers, for it to be understood and felt for many, if not most people, we need stories,” wrote Irene Reti (Kresge ‘ 82, environmental studies; M.A. ’04, history), director of the Regional History Project for the UC Santa Cruz University Library, and her co-manager for the project, Cameron Vanderscoff, in their introduction to the oral history. “The Empty Year calls for the deep listening of other people’s accounts to bind and cohere into something more whole.”

UC Santa Cruz’s Special Collections received special funding from UC Santa Cruz’s Counseling and Psychological Services, which provided the team with a Radical Resilience Grant. The project also received extra funding to pay stipends to the five students who are doing the interviews.

Undertaking such a project in the midst of a deadly pandemic had its logistical challenges. All interviews were done remotely, mostly via Zoom.

“All of us who were doing this documentation are in the middle of dealing with COVID-19’s impact on our own lives,’’ Reti said. “So it’s a tricky thing. It was very important to not do this work all alone, but as part of a team. It’s so important to build strong relationships among the student interviewers, and to think of the participants’ psychological health as they do this project.”

Student voices

The student researchers took turns interviewing each other to brush up on

the skills. But those practice interviews were revelatory. Interviews led to so much rich material that some of those sessions ended up in the archives.

Often, the interviewers’ own experiences in the pandemic and their research interests informed their questions. David Duncan, a Ph.D. student in the History Department, chose to interview two other history graduate students and a professor to find out challenges he knew firsthand: “How to juggle all these different commitments—grad student, teaching assistant, professor, and human being” in the midst of a crisis.

Duncan also wanted to ask them about the timing of the COVID crisis, during a year full of other challenges. Even before the pandemic hit, “we were already meeting at [downtown Santa Cruz dining hotspot] Abbott Square Market to work on our MAs because of the COLA strike,” he said, referring to a graduate student strike and walkout in 2019. “Also we were just coming out of the rainy season with multiple power outages.

“For me as an interviewer, I wanted to know how these narrators situated COVID in their own personal timelines of a very eventful 2020,” Duncan said.

Duncan mentioned a “standout moment” during his intensive interview with Associate Professor of History Benjamin Breen, who spoke of the ways a pandemic connects us with the past. Confronted with the horrors of COVID, Breen said that he could take some solace in history.

“The Great Plague of London, which lasted from 1665 to 1666, for instance, happened in the era of Descartes and Thomas Hobbes and Isaac Newton,” Breen said. “We think of it as a time of great creativity and innovation. During this time, there has been a lot of talk about how Newton was home from Cambridge University during the epidemic and developed, I believe, his theory of optics.”

Though Breen said it was important to avoid facile comparisons with the past, he feels a strong kinship with past stories of human suffering and how people of those times moved past it and overcame it.

Another interviewer, Isabella Crespin (College Nine ’22, anthropology and film & digital media double major), found the interviews surprisingly therapeutic.

“Most of the students I interviewed were not living on campus when I spoke with them,’’ Crespin said. “I think this project helps students feel like part of a community they have lost. I have also seen students struggle with a loss of independence after they moved back home with their parents.”

Crespin is one of those who moved back home during the pandemic, though it turned out to be an unexpected boon for her.

“All of my family relationships have never been better, and I am closer with my friends since I have made the commitment to regularly contact them,” she said.

A chance to preserve living history

Cameron Vanderscoff (Cowell ’11, history and literature—creative writing), one of the project’s managers, has a longstanding connection to campus: He’s a second-generation Banana Slug whose mother, Clare Henjum (Kresge ’74, education, environmental studies), and aunt, Peggy Henjum (Rachel Carson ’79, environmental studies), went to UCSC in the ’70s.

Vanderscoff, who runs his own oral history practice based in New York City, thinks of oral history as a way of giving the past a speaking voice.

“Oral history is a radically democratic act,” he said. “You’ll find that history isn’t some stuffy chore of memorizing rote dates and names, as it’s too often taught in our schools. Instead, history becomes live, shared in voices that are as powerful as that of any character you find in a novel or on Netflix.”

When it comes to UCSC’s experience of COVID-19, “it’s our hope that this archive can do that for our community’s experience of this extraordinarily hard time. This collection is a way of passing on a memory of this charged time.”

As he worked on the project, he couldn’t help but think, with regret, about the lost voices of previous pandemics.

“My grandfather, now 99 and the father of two UCSC alumni, was born one year after the end of the Spanish Flu,” he said. “I’ve been talking with him about how its shadow still appeared over his childhood. So plague isn’t new for humans. In other words: We’ve been here before.

“But we’ve failed to keep the memory—not only of widespread hardship, but also stories of community and resilience and survival,” Vanderscoff said. “Our hope is that this project, in its own small way, can keep that memory for whoever is ready to receive it in the future.”

A hardcopy version of The Empty Year is available for purchase.

The Humanities Institute co-sponsored ‘The Empty Year: An Oral History of the Pandemic(s) of 2020 at UC Santa Cruz’ as part of our 2021-2022 theme Memory.

Original Link: https://news.ucsc.edu/2021/05/covid-regional-oral-history.html