Dr. Caitlin Keliiaa is an Assistant Professor in the Feminist Studies Department at UC Santa Cruz and a THI Faculty Research Fellow for 2021-22. Dr. Keliiaa is currently at work on a book project titled Unsettling Domesticity: Native Women and 20th-Century Federal Indian Policy In the San Francisco Bay Area. Her manuscript explores the historical experiences of Native women who, through coercive contracting practices, worked as domestic servants in affluent homes across the Bay Area.

Dr. Caitlin Keliiaa is an Assistant Professor in the Feminist Studies Department at UC Santa Cruz and a THI Faculty Research Fellow for 2021-22. Dr. Keliiaa is currently at work on a book project titled Unsettling Domesticity: Native Women and 20th-Century Federal Indian Policy In the San Francisco Bay Area. Her manuscript explores the historical experiences of Native women who, through coercive contracting practices, worked as domestic servants in affluent homes across the Bay Area.

In our conversations this November, Professor Keliiaa offered us a glimpse into the book-writing process and shared some of the stories that animate her manuscript.

Good afternoon, Professor Keliiaa! Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with us about your current research. You’re working on a book project called Unsettling Domesticity: Native Women and 20th-Century Federal Indian Policy in the San Francisco Bay Area. Could you give us a snapshot of what your book project explores?

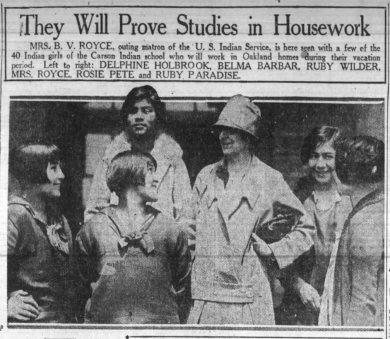

A 1927 Oakland Tribune article reporting that “forty Indian girls from the Carson Indian school at Stewart, Nevada will put their knowledge of domestic science to good use in Oakland during the vacation period.”

Unsettling Domesticity explores “outing.” Outing programs stemmed from U.S. Indian boarding schools and contracted out student labor to local white farms and homes. Where Indian boys might labor as farm hands, masons or blacksmiths, Indian girls solely labored as domestics. My book—the first comprehensive study of its kind—examines the Northern California-based iteration of this national Indian labor system. From 1918 to roughly 1942, the Bay Area Outing Program coercively recruited over a thousand Native women from Indian boarding schools to work as live-in housemaids in affluent homes across Berkeley, Oakland and the greater Bay Area. In exchange for room, board and menial pay, young Native women—as young as fourteen—cooked, cleaned, and served as caretakers in the private homes of their employers.

My book uncovers how Native women navigated the challenges and opportunities of the Bay Area Outing Program. I investigate how they negotiated the oppressive conditions of a program designed to assimilate them through gendered labor. I find that Native women resisted outing by fighting for higher wages, running away, and fighting to keep their children. Where I initially focused on resistance, I wrote two new chapters that highlight the structural forces of outing on the Native body. The chapters of my book engage Indian child removal, criminalization, sexuality, carcerality, health and labor. It advances existing work on Indian boarding schools, Urban Indians and contributes to the history of Native California.

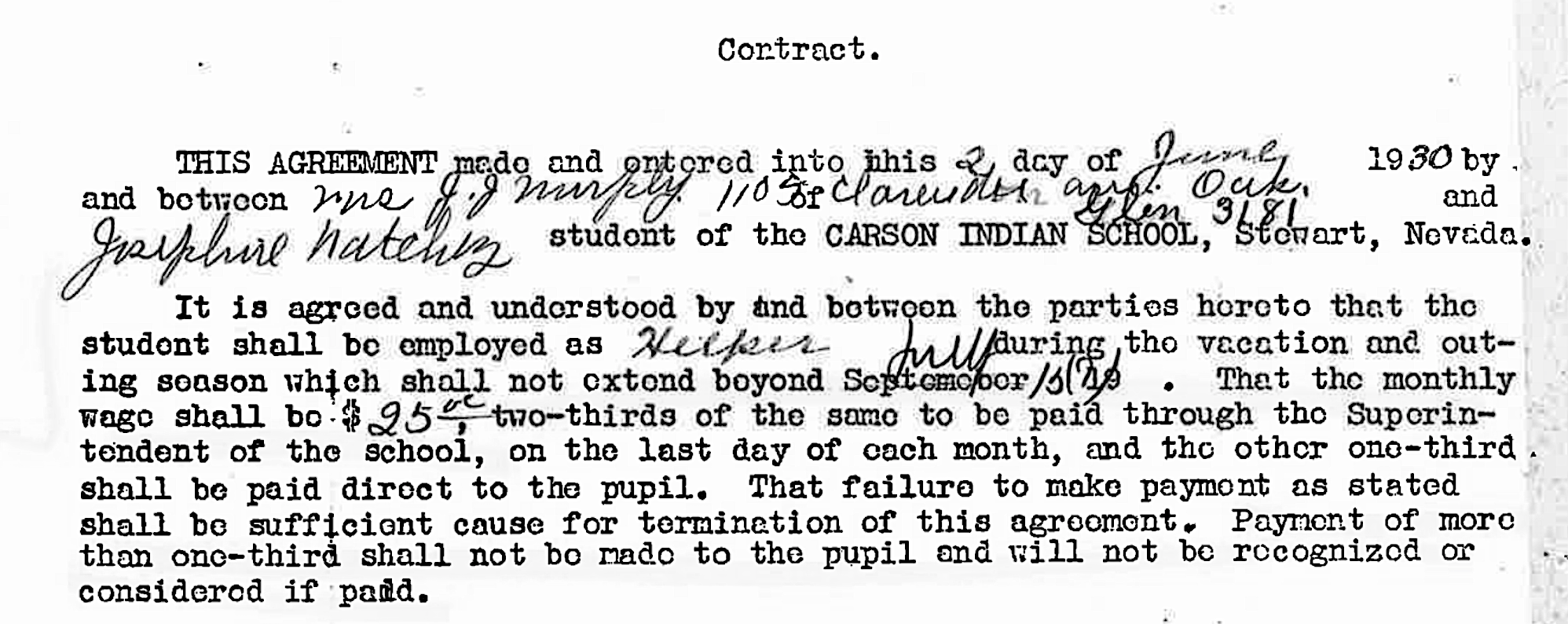

In June of 1930, Josephine Natchez signed this contract between herself, the outing matron, and her employer for the summer. The contract declared four main points regarding wages, how young women would be monitored and checked for disobedience, and the program’s gendered and supposedly “educational” intentions.

Your book sounds like it will be fascinating! What led you to pursue this research project? Were there certain experiences, like in the archive for example, that piqued your interest and solidified your commitment to telling these stories?

In the 1930s and 40s, my grandparents attended Stewart Indian School in Carson City, NV. After Stewart, my grandmother had a lifelong career as a housekeeper. I had always assumed that she was a housekeeper because it was the kind of work that she had access to. Much later, I realized that her being a maid was no mistake. Domestic work was the kind of labor that Indian boarding schools forced upon Native women. In grad school I wanted to explore this further and found that in the early 1900s, Stewart operated an extension of its outing program in the Bay Area. Thereafter, a former Stewart Matron officially established the Bay Area Outing Program. As I dove into the archive, I found rich files that illuminated each Native woman’s story. Some with painstaking detail such as instances when the Outing Matron attempted to separate outing mothers from their children. Through letters, bank statements and telegrams, I saw firsthand how Native women both acquiesced, and also challenged their liminal standing to assert their needs, resist surveillance and placate the Outing Matron. Their agency and will inspired me to tell this story.

This will be your first published book, many congratulations! What has the process of writing a first book been like for you? What would you say is the most rewarding and the most challenging part of this process?

Ultimately, I think the most rewarding part of the process is knowing that my work is bringing to life voices and stories that have been overlooked and unheard.

Thank you! I’m still very much in the middle of it, but as you can imagine, the process is not easy. However, researching and writing in the pandemic is especially challenging. Writing is often an isolating experience, but I think in the pandemic it feels that much more detached. Especially since I’m the kind of writer that thrives on caffeine in cafés! I lost that and had to make sense of writing exclusively from home. I also thrive in writing groups and in the pandemic much of those transformed to virtual co-working. That’s still the best way for me to write, but overall, it’s harder to stay focused and bounce ideas around. That being said, I wrote my two newest chapters on health and sexual surveillance during the pandemic, and I think it helped me process my frustrations and disappointment of living in this historic moment. I’ve been told those chapters are especially impactful and the conditions of the pandemic really shaped them. Ultimately, I think the most rewarding part of the process is knowing that my work is bringing to life voices and stories that have been overlooked and unheard.

As part of the Amah Mutsun Speaker Series, a joint project of UC Santa Cruz’s American Indian Resource Center and the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, you gave a talk recently called “Settler Colonialism is a Sickness: How Federal Indian Health Failed Native Women.” This talk, which draws on your book research, investigates the failures of federal policymakers and agencies to provide adequate medical care to Native women in the twentieth century. What kind of parallels do you see between this painful historical experience and current healthcare disparities affecting marginalized groups, especially during the COVID pandemic?

Unfortunately, nearly a hundred years later, there are still parallels. My talk took up the question of Tuberculosis (TB) among Native women in the outing program. In the early 1900s, TB was the cause of 40% of all Indian deaths. And by 1935, 17% of Native people were treated for TB. As TB ravaged Indian Country, the US Indian service was dangerously ill-equipped, and it cost Native lives. At the time, many prevailing theories pathologized Indian people and blamed them for contracting TB. These ideas reinforced the eugenic notion that the epidemic was inevitable, nothing could be done to fix it, and that federal officials and the structures thereof were not responsible. Decades later research discredited such theories—there was no connection between race and Tuberculosis. The disease that ravaged Indian county well into the mid-twentieth century was caused by extreme poverty. Settler colonialism shaped the circumstances that put Native people at higher risk of TB infection and death. Today, the COVID-19 pandemic has similarly shed light on vast inequity in public health, especially as certain racialized communities are more at risk of contracting the virus and dying from it. Conditions where people live, and work affect a range of health risks and outcomes. Factors, such as poverty and healthcare access have a significant influence on one’s health and quality-of-life. According to the CDC, as of September 2021, American Indian and Alaska Native people have 1.7 times more cases than their white counterparts, 3.5 times more hospitalizations and 2.4x more deaths than white Americans. Essentially, similar to TB in the early 20th century, Native people have a higher incidence rate. The silver lining in these grim COVID-19 statistics is a very high vaccination rate among Native American people. 58.5% of Native people have received at least one dose. And 50% are fully vaccinated. The fact remains that unless these systems change, this inequity will continue.

Your book foregrounds the historical experiences of Native women in the Bay Area. How do you imagine your book will deepen readers’ knowledge of the place that we live and study in?

And all this history starts with Native women.

I hope my readers will gain a deeper understanding of Urban Indian history, the Bay Area, California and the West. Many people, even within Native American Studies backgrounds are not aware of outing programs, much less urban-based programs. And broadly Native people are often thought of in the frame of land dispossession rather than labor exploitation. But the history of the Bay Area Outing program builds on both of those elements, particularly as it relates to the history of California. And in this work, I highlight the genealogy of the Bay Area Indian community. On their day off, outing women and girls organized in a club called the Four Winds Club. It was a central intertribal meeting place for Native women in the Bay Area where they created community and space. Over the decades this club grew to include Indians from other realms of the Bay Area, including college students and military personnel. Native men also became involved in the Four Winds Club. In 1955, many of the people from this original Urban Indian organization created the Intertribal Friendship House in Oakland, CA. To this day, “IFH,” as it is affectionately known, is the backbone of the urban Indian community in the East Bay. And all this history starts with Native women.