“My own struggles growing up as a Chinese-Vietnamese American have helped drive home the concept that history and the humanities are incredibly relevant in the modern era, where STEM seems to reign supreme,” says Robert Potmesil, a UC Santa Cruz History undergraduate who was a Humanities Institute research fellow and the recipient of the Bertha N. Melkonian Prize.

He came to Santa Cruz intending to study the antebellum America, but things took a turn when he joined a class taught by Alice Yang. “It was there I had an epiphany,” he says. Learning about the “boat people” who fled Vietnam in the late 1970s, the details his mother shared growing up gained new meaning. She was one of the many ethnic Chinese refugees who escaped Vietnam in 1979 due to targeted persecution by the Vietnamese government.

“I ostensibly knew this—mainly due to statements such as ‘When I was your age, I was in a refugee camp!’” he says. But he had not fully considered the cultural impact on his family or his own identity.

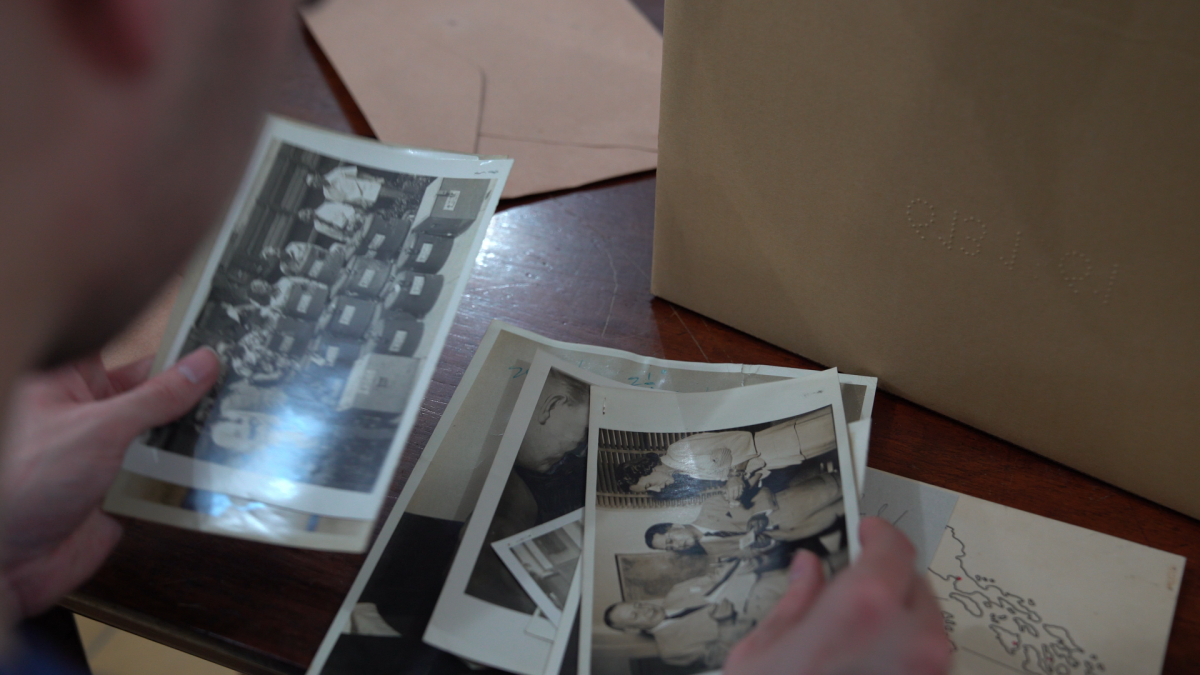

The revelation would prompt a groundbreaking independent study project and a return to that refugee camp in the Philippines with his mother as his guide. “When I started the project, I realized that I had to get hands-on historical research,” he says. “I could interview family all I wanted, but if I wanted to get to the heart of what’s causing the cultural identity issues that refugees face, I needed to go to the camps themselves.”

Robert got support from his advisors, the aforementioned Professor Yang and also Professor Alan Christy, as well as The Humanities Institute. “If I didn’t have the access to resources, I wouldn’t be able to do any of this,” he acknowledges.

The young scholar also worked on The Humanities Institute-supported Gail Project, which studies life in post-war Okinawa, Japan. In an effort to make history more compelling and impactful, he has experimented with forms of storytelling, including video and podcasts. “I want people to realize that history is really really interesting,” he explains. “They love it, they just don’t know it yet.”

While deeply personal in its origins, Robert’s scholarship has wide-ranging implications. According to the UN Refugee Agency, there are more displaced people and refugees today than any other time in history. The immediate humanitarian concerns are well understood, however few people are thinking about the long-term cultural impacts this crisis engenders in families like Robert’s.

As he explains, “in the pursuit of understanding my own cultural heritage, I have learned how such research may be relevant to many other Americans seeking to understand their own identity.” Robert Potmesil’s revealing study of identity and culture shows that a modest investment in a bright young mind can produce incredibly rich rewards.