Amanda Huse is a PhD candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. Huse’s dissertation, “‘She was afraid I would tell it’: Women and Ku-Klux Violence in Postwar, Post-Emancipation Georgia,” concerns the historically overlooked role of white women as active participants in Ku-Klux Klan networks and the perpetuation of anti-black violence. This summer, we learned more about Huse’s project and her time doing archival research in Georgia. We discussed the tendency for historians to confine women to passive roles, the challenges of close reading approaches to historical testimonies, and the use of digital technologies like Gephi to support qualitative research.

Amanda Huse is a PhD candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. Huse’s dissertation, “‘She was afraid I would tell it’: Women and Ku-Klux Violence in Postwar, Post-Emancipation Georgia,” concerns the historically overlooked role of white women as active participants in Ku-Klux Klan networks and the perpetuation of anti-black violence. This summer, we learned more about Huse’s project and her time doing archival research in Georgia. We discussed the tendency for historians to confine women to passive roles, the challenges of close reading approaches to historical testimonies, and the use of digital technologies like Gephi to support qualitative research.

Hi Amanda! Thank you for chatting with us about your ongoing research! To begin, would you provide us with an overview of your dissertation project and what specifically you worked on over this past summer?

Hi Kirstin, thank you for having me. My dissertation is focused on the actions and experiences of women in the post-Civil War, post-Emancipation era. The Reconstruction period is studied and known for turbulence, violence, and opportunity, but historians have often continued to confine women to roles as victims and passive supporters of the violence and politics of the era. In both scholarly and popular representations, the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan, in particular, stands out not only as an organization dedicated to white supremacy but also as one dominated by men. Recent scholarship by historians like Hannah Rosen and Kidada Williams has drawn attention to the Ku-Klux targeting of women for violence, roundly refuting the chivalric pretensions of the Klan and its twentieth-century proponents. Yet, even this nuanced new generation of scholarship has failed to recognize that women were not just victims of Ku-Klux violence. My research examines how many white women were active participants in Ku-Klux networks who, at times, directed the violence itself. Accordingly, my dissertation examines women’s connections with the nineteenth-century Ku-Klux organizations in Georgia and seeks to define the scope and nature of their involvement in postwar, post-Emancipation violence. Further, my project challenges the tendency to equate being a victim with being a passive historical actor. Instead, I argue that investigating why the Ku Klux targeted certain women for violence can shed light on woman’s engagement in the political and economic networks of their communities.

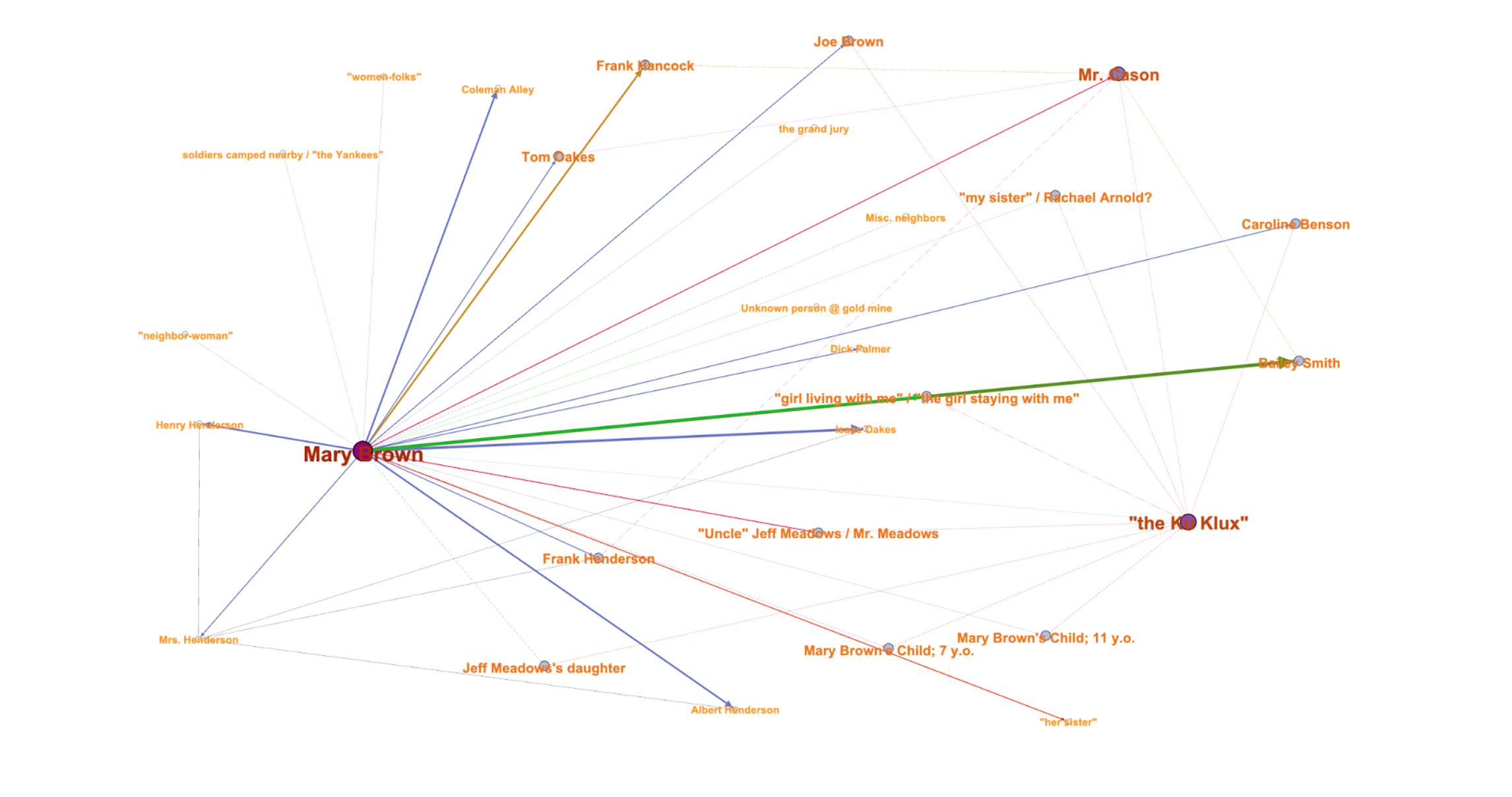

This past summer, I spent time mining sources to uncover such networks in several counties in Georgia, particularly documents where women’s perspectives are more clearly visible, such as court cases and family letters, in addition to examining direct testimony. I’ve been using a close reading methodology to get at the qualitative information in the sources while also building a digital database of community members and interactions in the community. I’m using this database to build social network maps using the software Gephi to help find patterns that I might miss by just studying the qualitative information.

How did you first become interested in Reconstruction-era Georgia, and more specifically, in the capacity of women to wield political power during this time, particularly through their participation in the Ku-Klux testimonies?

19th-century record book from the White County, Georgia, Superior Court. Photo taken by Amanda Huse at the White County courthouse in Cleveland, GA.

I became interested in Reconstruction-era Georgia when I first stumbled upon the Ku-Klux testimonies as an undergraduate student at UC Davis. I ended up writing my senior thesis on the testimonies, and it is what actually led me to apply for graduate school. Over several years, I read and reread the testimonies and noticed new details each time. But my real breakthrough came when I collected all of the testimonies from the same community together and read them as a whole rather than piecemeal. It was there that I discovered the subtle interactions occurring between women, which do not always appear evident in the testimonies because they are guided by the questions of congressmen who do not seem particularly interested in what women were doing. A close reading of testimonies from one place, White County, Georgia, led to my master’s essay, “‘I do not intend to tell anything but the truth’: Freedwomen, Testimony, and Ku-Klux Violence in Reconstruction Georgia.” It was there that I began to hone in on the interactions between two women, Mary Brown, a freedwoman, and Mrs. Henderson, the wife and mother of several members of the local Ku-Klux gang. Mary Brown’s case has been studied before because she was a key witness in the murder of a federal marshal during a conflict over the illicit distilling of alcohol in White County. But historians have often examined her case in relation to the men in the community, including those distilling, members of the Ku-Klux gang, and her husband, Joe Brown. When I began using a close-reading methodology on Mary Brown’s testimony, however, I noticed she discussed Mrs. Henderson as someone integral to the attack on the Brown family. I think instances like these two women’s movements in the community and their relationship with one another need to be explored in more detail in the historiography so that we can better understand the significance of women’s actions during this period. The titles of both my master’s thesis and my dissertation are quotes pulled from Mary Brown’s testimony; my dissertation title is a reflection on the fact that it was Mrs. Henderson who first directed the violence against the Brown family because she was afraid of Mary Brown’s testimony. That case has been the foundation of my research, but I have since found similar instances in the testimonies of women that have allowed me to examine other communities in Georgia concurrently.

Over the last few years we have seen a surging interest in reparations campaigns, even on the national political stage. How do you think your work might contribute to these conversations, and historicize the roles women have played in fighting for redress against historical violence?

The tendency for our meta-narratives is often still to focus on those who are in a position of privilege because their voices are the easiest to find.

I think my work can contribute to our collective understanding that women are not outside of violence, historical or otherwise, nor are they outside of politics, even when they are underrepresented. It seems like an obvious statement, but the tendency for our meta-narratives is often still to focus on those who are in a position of privilege because their voices are the easiest to find. When women are victims of political violence, there can also be a tendency to equate that with powerlessness, or relate it to what their husbands and fathers were doing in the official realm of politics. Furthermore, understanding that some white women were active participants in violence reveals a part of the historical narrative that has been mostly ignored. Historians like Thavolia Glymph, Stephanie Jones-Rogers, and Stephanie McCurry have all demonstrated women’s active roles in the violence of slavery and the Civil War, and I think my specific work examining women and Ku-Klux violence can contribute to that field.

This is a social network map of a small subset of data mined from Mary Brown’s testimony, generated using Gephi software.

You spent time doing archival research at the Georgia State Archives and at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library of Emory University in Atlanta. I imagine this archival research revealed a host of fascinating documents, histories, and stories, but was there a specific text or a specific moment that stands out to you from your research–a moment of surprise, shock, awe, or understanding you’d like to share with us?

Some of the most interesting documents that I’ve come across in the archives have been local court cases that have been archived. Court cases are interesting to me because, like testimony, they are an avenue for regular people to make it into the archives. It’s one of the places where historians can look at some of the motivations of people who didn’t have estates or big family collections of papers. Women also appear in these documents more than in other official sources. Many of the cases are about money and property, but others are about things like slander or divorce, and sometimes you can get a feel for what mattered to these individuals.

How has fellowship support from THI helped you in your research and writing process?

Support from THI has enabled me to travel to Georgia for research and stay longer than I would otherwise be able to.

Support from THI has enabled me to travel to Georgia for research and stay longer than I would otherwise be able to. I have visited the Georgia state archives twice now and spent time on both trips immersing myself in documents that I would otherwise not have been able to study. I was also able to rent a car and visit smaller archives in the area, including driving up to a rural county in northern Georgia, meeting with a local historian at the county historical society, and examining original documents from the nineteenth century in their courthouse that have never been digitized.

Finally, where is your favorite place to write?

My backyard! I am writing my responses to your questions there right now.

Banner Image: The Ku-Klux reign of terror. Synopsis of a portion of the testimony taken by the Congressional investigating committee. No. 5. [n. p. 1872]. From the Library of Congress.