Anne Napatalung is a PhD candidate in Feminist Studies at UC Santa Cruz. Napatalung’s research centers around the Tuskegee School of Midwifery (1941-1946) in Alabama, framing it as a potent historical site for exploring the ways vibrant minoritized care networks were suppressed and criminalized as a part of the racist institutionalization of reproductive medicine.

Anne Napatalung is a PhD candidate in Feminist Studies at UC Santa Cruz. Napatalung’s research centers around the Tuskegee School of Midwifery (1941-1946) in Alabama, framing it as a potent historical site for exploring the ways vibrant minoritized care networks were suppressed and criminalized as a part of the racist institutionalization of reproductive medicine.

In September, we learned more about Napatalung’s dissertation project. Napatalung received a THI Summer Dissertation Fellowship in 2022 to support her dissertation writing and further fieldwork in Alabama. We discussed Napatalung’s archival and sensorial approach to research, the importance of a transnational approach to the history of midwifery, and the legacies both of white supremacist, patriarchal control, and Black and Indigenous embodied knowledges in reproductive justice struggles.

Anne, thank you for chatting with us about your ongoing research! To begin, would you provide us with an overview of your dissertation project and what specifically you have been working on this summer?

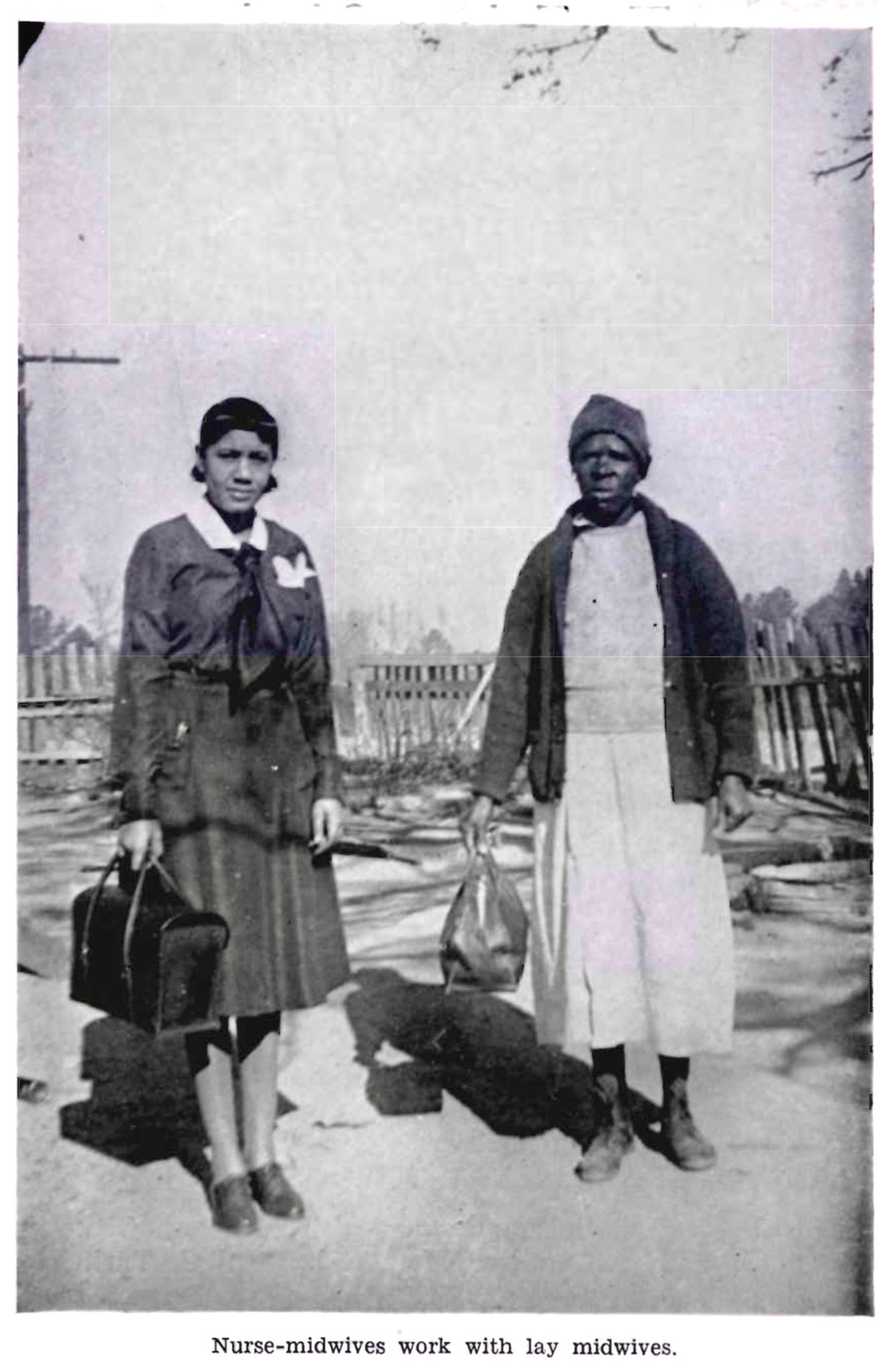

Thank you so much for reaching out! My dissertation project, “Re-membering Healing: The Tuskegee School of Midwifery and its Legacies for Reproductive Care,” frames the Tuskegee School of Midwifery (1941-1946) in Alabama as a rich, understudied historical site, entangled in local, national, and transnational circuits of knowledge. I examine the resonances of OB/GYN as a medical field formation which emerges in Alabama, consider the suppression of the Black and Indigenous lay midwife in relation to the Tuskegee Institute as a private, land-grant HBCU, and trace the criminalization of informal medical knowledges through circuits between Alabama and Haiti. I rely on an abundant archive of cultural and sensorial knowledges to illuminate the active suppression of vibrant minoritized care networks. Such networks have long been relied on for Black and Indigenous health and survival, and in my account, offer timely possibilities for more expansive definitions of reproductive medicine, care, and healing.

With the support of the THI Summer Dissertation Fellowship, I’ve had the opportunity to return to fieldwork in Alabama for the first time since 2019. Driving is quite necessary to move across the South, so I’ve been stopping at museums and archival sites during my research travels. Though I grew up in the region, these embodied experiences continue to expand how I relate to the land and my own project. For example, the Birmingham Civil Rights, Freedom Rides, and Rosa Parks museums have really deepened my understanding of the racial, gendered, and police violence that uniquely shapes 1940s Alabama in the years leading up to the Civil Rights era, as well as the anti-Communist sentiment that targeted Black and multiracial organizing at the time.

Napatalung with Tuskegee Archivist and Digital Humanities Project Manager, Marvin Byrd

Critically, I’ve been able to spend the bulk of my time at Tuskegee’s archives, campus, and surrounding areas, and revisit relationships formed during 2019 field work. Given that very few documents related to the midwifery school remain and given the growth of my own project since 2019, returning to the school’s nursing, medical, and funding archives and its on-campus museums has been enriching and timely as I move into a year of dissertation writing. Visiting the Tuskegee National Forest and Indigenous cultural sites has also given me a more layered understanding of the living and historical social, ecological, and political struggles that shape what it means for Tuskegee to take form as a land grant university.

This sounds like such a rich and important project! How did you first become interested in the Tuskegee School of Midwifery, and the history of midwifery more generally?

My doula practice began through organizing with birthworkers of color in and outside of the U.S., and as a result, it also began with an awareness that Black and Indigenous midwifery knowledges were the foundation of birthwork in the U.S. context. These histories are often left out of mainstream, predominantly white, birth education and trainings and U.S. modern medical education more broadly. The international field of modern OB/GYN in particular forms in relationship to the knowledge of Black and Indigenous midwives in the Tuskegee area.

When I transitioned from nonprofit work to graduate school, my former advisor, Dr. Brittney Cooper and my current advisor, Dr. Gina Dent both nurtured my ongoing question of what healing might look like in the context of structural violence and harm. Professor Dent encouraged me to follow the strand in my work related to the ways in which community-based midwifery and healing knowledges were and are supplanted. We discussed Tuskegee University as a site of inquiry in one of our early meetings, and when I found out about the midwifery school and its preceding midwifery projects, an entire world opened up for me. The midwifery school is only in operation for a few years, and most of the school’s related documents are lost or intentionally destroyed by the university and its funders.

This all occurs in a state known for having an abundance of Black and Indigenous lay midwives, during a time when they are increasingly policed and criminalized by U.S. medicine and law. Due to my feminist training and my experiences with elder birthworkers of color, I’m attuned to the ways in which these modalities of care can be narrated as disappeared or absent in relation to dominant models, when they in fact persist in more subtle or less traceable ways. As doula and midwifery care are once again at a crossroads of gaining recognition and formalization through Western legal and medical frames, I find an urgency in learning from Tuskegee as a cautionary tale. In my project, I consider what it would mean to account for and defend the labors of Black and Indigenous midwives, who have been positioned as the antithesis of modern OB/GYN from its origin in the U.S. South.

Although situated in Alabama and the American South, your project also investigates the interrelated historical experiences of midwives and medicalization in other places like Haiti and the wider Caribbean. Why is a transnational approach key to understanding the history of midwifery and midwife training that your dissertation project explores?

Photo Courtesy of Tuskegee University Archives

Anna Julia Cooper and Julius Scott’s works really shaped my thinking about the U.S. South and Haiti as sites of Black knowledge exchange, and also spurred me to consider the intellectual and material debt owed to the country, as a U.S. based scholar and citizen implicated in the afterlife of the U.S. occupation of Haiti. My preliminary archival research in 2019 made it clear to me that students from all over the world, the Caribbean, and Haiti in particular, were attending Tuskegee from its outset. When I was limited to secondary materials due to COVID leading up to my qualifying exams, I continued to read about Black intellectual debates related to the U.S. occupation of Haiti, as well as Tuskegee’s place within that web.

My masters research traced reproductive policy through circuits between the U.S. and Palestine, so I was already thinking across borders and outside of Americocentric frames in order to trace U.S. settler colonialism and imperialism in birthwork. Haiti is consistently named the country with the highest maternal death rate in the Western hemisphere, and given Tuskegee and Haiti’s longstanding relationship, particularly through education, funding streams, and medical experimentation, I began to think about how Black and Indigenous midwifery care in both sites has been and continues to be supplanted through prominent philanthropic and medical educational infant and maternal health models.

The historical terrain that I lay out brings the intimacies between Alabama and Haitian midwives into view. The figure of the Black and Indigenous midwife – often positioned as a trusted healer within community forms in precolonial, colonial, and plantation life – is pathologized through racial and gendered imaginaries rooted in “the idea of Africa” (V.Y. Mudimbe), which circulate across borders in service to shoring up modern medicine. The midwife is also targeted in part because of a fear of their role and power in community, their allyship with plants and land, their proximity to social and biological reproduction, and their relationship with Spiritual technologies that have long fortified the imaginations of colonized and enslaved peoples seeking freedom. So the process of crafting the young white male physician as medical expert becomes a uniquely difficult and violent process in the case of OB/GYN, wherein for centuries the primary caregivers across racial boundaries were Black and Indigenous elder feminine figures.

Over the last few years, especially as reproductive freedom has come under intense scrutiny and attack, researchers have noted the racial and ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. How do you think your work may help to explain and historicize the maternal health disparities currently impacting women of color?

Most of the practitioners of color I’ve engaged with in the U.S. and beyond have always been asking more complex questions regarding what reproductive care looks like within systems of violence – from U.S. settler colonialism and imperialism, to slavery and structural racism, to state healthcare and the law, to heavily policed neighborhoods, ICE facilities, and prisons. With a project grounded in reproductive justice struggles, I am reminded that popular demands for what is possible in terms of care and health can be expanded through historical memory and collective study.

Napatalung at The Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University

For example, while we have witnessed public outrage over the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade, reproductive justice struggles have taught me that Roe has always been technically vulnerable. Through the very logics of reproductive rights and the position of women of color within U.S. law itself, many of the most minoritized folks, poor folks, and folks without access to healthcare, have never fully had the right to make decisions about abortion for their own bodies in the U.S. In a similar vein, the fact that J. Marion Sims, known as the “founding father” and “architect” of modern OB/GYN, conducted his experiments on enslaved Black women, has become more commonly discussed in the birth world and beyond. In recent years, we’ve seen demands for his statue to be removed in multiple sites. Inspired by popular struggles, I trace the ways in which Sims’s persisting medical architecture has also normalized violative forms of touch, racialization, binarized gender, and patriarchal control, as well as anatomical mappings that cannot account for a range of pleasures, sensations, and possibilities for reproductive healing.

In my work, infant and maternal health disparities for Black and Indigenous people in the U.S. and in Haiti are unfortunately not new. As a result, I consider how the medical frames that repeatedly produce these tragic circumstances are neither fully represented nor held accountable. Here, I bring into view U.S. modern healthcare, dominant nonprofit and medical educational models, and the afterlife of the U.S. occupation of Haiti as active contributors to infant and maternal mortality. I also frame the dismantling of local reproductive care networks as ongoing systemic violence and trace intergenerational trauma and intergenerational healing at intimate and collective scales. My project is in conversation with historical and popular reproductive justice struggles, in service to more expansive imaginaries of what reproductive medicine, education, health, and care can be.

My project is in conversation with historical and popular reproductive justice struggles, in service to more expansive imaginaries of what reproductive medicine, education, health, and care can be.

Finally, how has the THI Summer Dissertation Fellowship helped you in your research and writing process?

Though I was able to conduct preliminary research in Tuskegee in 2019, COVID restrictions from 2020-2021 delayed my return to Alabama prior to and following the defense of my qualifying exams. Fortunately, I was able to build my qualifying exam project through secondary sources, archival notes, and digital materials, but completing field work remained essential. Many sites and archives have recently opened for the first time in two years, and the THI Summer Dissertation Research Fellowship gave me the opportunity to return to Alabama and complete on the ground research. As I enter a year of dissertation writing at the conclusion of my travel, I feel well-equipped to maintain my dissertation timeline, with a rich selection of archival materials and research notes, and the momentum of summer travel. I am incredibly grateful for THI’s generous support of my research and writing during this critical time.

Banner Image Courtesy of Tuskegee University Archives