Grad Profile: Crystal Smith

Crystal Smith is a PhD Candidate in the History Department at UC Santa Cruz. Smith studies how the British Empire was promoted and sold to middle-class Britons through sensationalist journalism, new media, and reports of imperial scandal. According to Smith, the marketing of empire through this often apocryphal “new journalism” conjures up comparisons to the contemporary pervasiveness of “fake news.”

In September, we learned more about Smith’s research. Smith was selected as a THI Summer Research Fellow in Summer 2021 and a THI Graduate Student Success Peer Mentor in 2019-2020. In our interview, we discussed ongoing archival research and the scope of the dissertation.

Thanks for taking the time to speak with us, Crystal! To begin, would you mind just telling us in broad strokes about your work? What are the main things you research and focus on?

My research focuses on the connection between the media and imperialism in the late nineteenth century British Empire. Specifically, I am interested in how the empire was promoted and sold to middle-class Britons and how imperial scandals complicated that promotion. In order to sell this imperial product, newspapers, corporations, and humanitarians relied upon a racial hierarchy in which white men of good “character” served as ambassadors and agents of civilization to Britain’s colonial subjects through the promotion of liberal and Christian values.

It sounds like your work brings together a lot of different bodies of scholarship and kinds of sources. How does this approach build from or challenge historiographical paradigms within your field?

My field has certainly concentrated on what Antoinette Burton calls “domestic imperial culture.” New Imperialist History of the British Empire in the last few decades has concentrated on how imperial experiences shaped the colonizer’s conception of whom they were with a focus on national popular culture. My work builds on this focus on popular culture and media by focusing on the moral connection between scandal and empire and what that says about the morality of empire in actuality and in ideology.

Your current research project, titled “Empire Incorporated: Media, Liberalism, and the Productization of the British Empire in Africa, 1885-1890,” seems fascinating. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

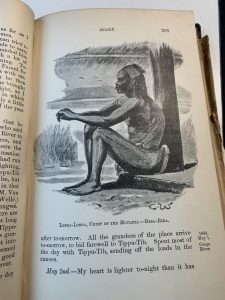

“Empire Incorporated” uses the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition (EPRE) as a case study for understanding the role of imperial scandals in promoting the empire to the British middle class. The ERPE (1887) was an effort led by various European groups to extract Emin Pasha, a German-born governor, from the southern Sudan province of Equitoria after Muslim revolts destabilized the region. What is interesting about the EPRE is the motley crew of figures that participated. And the scandal that is at the heart of its notoriety is that the heir to the Jameson Whiskey fortune was implicated in an act of cannibalism. The expedition had been promoted and financed by a highly coordinated partnership with British newspapers by connecting Emin Pasha with his boss General Charles Gordon (who had recently been martyred in the Mahdist Uprisings) and the cause of anti-slavery. And yet what it later revealed was that the expedition was largely part of a money making partnership between the Imperial British East Africa Company, Henry Morton Stanley, and the Congo Free State. You also get these stories of horrible abuse, violence, and mutiny connected with the expedition’s rear guard. One of those stories was the accusation of cannibalism lodged at James S. Jameson.

This sort of exploration of politics, myth, and media seems quite timely. How do you see your project in light of current dynamics in these areas? What do you think are the present stakes of this kind of research?

The time period that I focus on, 1885-1890, saw the rise of what some called at the time “New Journalism.” Newspapers were targeting a broader lower-middle and working class audience and they used a style that emphasized sentiment over intellectualizing which definitely elicits comparison to our present moment of “fake news.” Due to the greater reach and availability of late Victorian newspapers, popular opinion and sentiment could more easily be swayed and appealed to, leading to a more sensational style of journalism. Much like the new journalists of the late 60s, the Victorian new journalist became a celebrity by being part of the story, rather than an impartial observer.

During the 2020-2021 cycle you were a THI Summer Research Fellow. How has THI support contributed to the development of your project?

Unfortunately, due to COVID, I’ve had to postpone my archival research to the spring, but I wouldn’t have been able to plan this trip without the support of THI. But, having the opportunity to do a longer research trip will have a huge impact on my ability to finish my dissertation. In the Spring, I’m planing to travel to London to complete my archival research, looking at collections pertaining to the British Imperial East Africa Company, William Morton Stanley, and groups like the British Anti-Slavery Society and the Aborogines Protection Society.