Grad Profile: Emily Travis

Emily Travis is a PhD candidate in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. Her dissertation explores autotheory as a feminist impulse undergirding documentaries about women celebrities. In February, we learned more about Travis’s research and her extensive work as a THI Public Fellow with Prison Journalism Project, a nonprofit organization that works with incarcerated and incarceration-impacted writers to train them in journalism and help them reach a wide audience through publication.

Emily Travis is a PhD candidate in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. Her dissertation explores autotheory as a feminist impulse undergirding documentaries about women celebrities. In February, we learned more about Travis’s research and her extensive work as a THI Public Fellow with Prison Journalism Project, a nonprofit organization that works with incarcerated and incarceration-impacted writers to train them in journalism and help them reach a wide audience through publication.

Hi Emily! Thanks for chatting with us about your public fellowship work and your ongoing research. To begin, could you give us a general synopsis of your dissertation project?

Hi, Kirstin! Thank you for the opportunity to chat about my research and Public Humanities work.

My dissertation, Documenting the Stars: Autotheory and the Language of Celebrity in the Americas, explores the possibilities and limits of autotheory as a feminist literary form by close-reading three films that feature, to borrow a phrase from Nathalie Léger, “a woman telling her own story through that of another woman.”

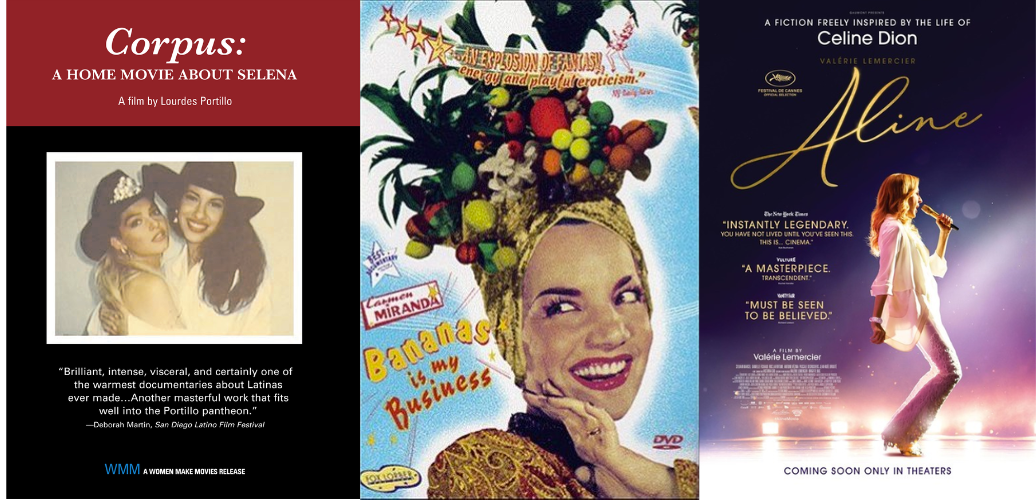

I examine Valérie Lemercier’s Aline (2020), in which Lemercier plays a fictional Québécoise character based on Céline Dion; Helena Solberg’s Carmen Miranda: Bananas Is My Business (1995), in which Solberg presents dramatic reenactments of her own dreams and historical artifacts from Miranda’s life as equally valid documentary sources; and Lourdes Portillo’s Corpus: A Home Movie About Selena (1999), in which Portillo questions how the life and death of Selena Quintanilla-Pérez informs the constellated identities of young women in Corpus Christi and beyond.

I argue that Aline, Bananas, and Corpus are each animated by what Lauren Fournier calls an “autotheoretical impulse,” or the author’s tendency to theorize the self in relation to the world using creative methods; however, what makes these films stand apart is that they leverage celebrity figures as a mode for theorizing the self. Although the films are based on the lives of real people—Dion, Miranda, Quintanilla-Pérez—the filmmakers understand that celebrity functions as a kind of transnational language, a shorthand through which fans can express aesthetics, ethical values, sexual desires, and more. Specifically, I’m interested in how the films use the language of celebrity to communicate and co-elaborate new stories about American women’s experiences with international audiences.

In the Summer of 2022, you worked with Prison Journalism Project as a THI Public Fellow. Can you share what drew you to this organization and what you spent the majority of your time working on?

As an autobiography scholar, I was initially drawn to PJP’s emphasis on the political power of first-person narratives. PJP trains incarceration-impacted journalists to report on the criminal justice system using first-hand observations and experience. By publishing their work, PJP offers incarcerated writers a platform to bring more transparency to the conditions of prison life and participate in public conversations about policies that directly impact them.

I am impressed by the range of first-person genres PJP publishes: As a news archive, PJP’s online publication is formally and topically diverse. Each of the stories makes a powerful but unique argument about the state of the U.S. criminal justice system using a distinct mode. You’ll find collections of reported essays that challenge carceral logics and report on the conditions of life inside, like the “Aging in Prison Special Series”; personal essays about healing and heartbreak, like Andrew Suh’s “Happiness, Healing and Hot Jook: How I Found My Korean Prison Dad”; humor pieces that will leave you howling, like Calen Widden’s “I Literally Live in a Bathroom”; poetry that crackles with sensory details, like George T. Wilkerson’s “The Noisy Blanket”; and visual art that insists that we view the experience of incarceration from the inside out, like Jessie Milo’s “House of Milo.”

When I began my fellowship, I spent a few weeks as an assistant editor, which allowed me to become familiar with these different genres. Since then, I have worked as a project manager for the development of PJP’s media writing handbook. I’m excited to be part of this process; the handbook is a first-of-its-kind educational tool designed to provide incarcerated writers with resources and guidelines for reporting news from inside.

I’m wondering how your work on the media writing handbook has influenced your pedagogical approach to the undergraduate classroom?

I’ve joked with my students for years that templates are my love language, and my work on the handbook has only made me more committed to the value of templates.

It’s easy to feel siloed off while working on a major project, like a dissertation, but when I step back to consider all of the generous interlocutors in my own work, the burden feels a little lighter.

Every incarcerated writer at PJP comes to journalism from a different cultural and educational background, with varying kinds of experience and access to reference resources. The handbook is designed to meet each writer where they’re at, wherever that is. Each section of the handbook includes an “anatomy” of a published news story with annotations and a template for writing stories in that genre. The idea is to show as well as tell writers how journalism works.

I use the same approach when working with undergraduate students in literature and writing courses at UCSC. Whenever possible, I source or develop annotated examples and templates for writing, and I tell my students, “If you don’t know how or where to start, or if you’re feeling stuck, here’s a framework you can use. Just drop your good ideas into it. Use it or don’t, but it’s here for you.” Taking time to go over writing conventions instead of making assumptions about what we might already know helps us all feel more confident.

Your work with PJP sounds gratifying, edifying, challenging, and exciting. Could you share a single anecdote, learning experience, piece of writing, or personal interaction that stands out from your time working with PJP?

My visit to San Quentin State Prison, which is the site of San Quentin News (SQN), an award-winning, grant-funded independent newspaper managed and distributed by incarcerated journalists.

When I reflect on the different threads of my work, what stands out to me is the importance of recognizing all writing as collaborative practice.

As part of the tour for PJP Bay Area employees, we were invited to sit and chat with writers in the bullpen of the SQN newsroom, including veteran PJP writer, Joe Garcia. Our conversation occurred adjacent to where the Pulitzer Prize nominated podcast, Earhustle, is recorded. The walls were lined with archival copies of SQN dating back decades and punctuated with absences—years during which the paper was censored by prison administrations. The visit was a reminder of how powerful prison journalism can be, and how limited the conditions of prison reporting still are.

What, for you, is the connection between your work with PJP, your academic research, and your own writing practices?

When I reflect on the different threads of my work, what stands out to me is the importance of recognizing all writing as collaborative practice.

I consider my work with students as a form of co-writing, from discussion to draft to revision to final submission (rinse repeat). The editorial process at PJP is likewise a collective effort, from reporting and interviews to editing and publication. What appears on the (web)page is only part of the story.

My research hinges on this idea: I often encounter autobiographical texts that are heavily mediated and formally defined by a kind of hybrid authorship. I read the films at the center of my dissertation as ephemeral recursive reading and writing encounters between filmmaker, subject, and audience.

It’s easy to feel siloed off while working on a major project, like a dissertation, but when I step back to consider all of the generous interlocutors in my own work, the burden feels a little lighter.

Listen to what incarcerated journalists have to say, and what they think you should know about life inside.

What do you want others to know about PJP’s work? What are you going to carry forward from your time with the organization?

Read the stories. Listen to what incarcerated journalists have to say, and what they think you should know about life inside. Let these stories inform your understanding and your responses to those impacted by incarceration and to the sorts of decisions we make individually and as a society about incarceration.