Grad Profile: Manning Chan

Manning Chan is a PhD candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. Chan’s dissertation, “Music, Tradition, and Power: A History of Qin-zither in Early Modern China” traces the history of qin-zither music in China, with an emphasis on the role this music played in shaping political, social, and cultural norms and values. This summer, we learned more about Chan’s project and her upcoming archival research trip to Hong Kong. We discussed the relationship between scholarship and aesthetic musical taste, approaches to archival research, and Chan’s own experiences as a player of the qin-zither.

Manning Chan is a PhD candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. Chan’s dissertation, “Music, Tradition, and Power: A History of Qin-zither in Early Modern China” traces the history of qin-zither music in China, with an emphasis on the role this music played in shaping political, social, and cultural norms and values. This summer, we learned more about Chan’s project and her upcoming archival research trip to Hong Kong. We discussed the relationship between scholarship and aesthetic musical taste, approaches to archival research, and Chan’s own experiences as a player of the qin-zither.

Hi Manning! Thank you for chatting with us about your ongoing research! To begin, would you provide us with an overview of your dissertation project and what you are focusing on right now?

Thank you for having me, Kirstin! In my dissertation, I will write a history of qin-zither music in late seventeenth to eighteenth-century China by paying special attention to its power relations embedded in the duality of state and elite. By dissecting the parallel yet intertwined state and elite relationship in the tradition-making of music, my research will re-evaluate qin-zither music’s political, social, and cultural role in early-modern China and unearth how power entered the seemingly autonomous realm of individual taste and cultural life. Currently, I am working on the Qing state and the Chinese elite’s cultural logic and power relations regarding the reinvention of high qin-zither culture in the Kangxi reign (1661-1722).

Your project explores the cultural prestige of the qin-zither in early modern China. For you, what can we learn about the cultural landscape of a certain time and place by paying attention to the hierarchy of musical tastes?

Discussions on musical taste were, in fact, the convergent point of political, commercial, and cultural powers in which we see how a musical instrument can be simultaneously a revolutionary and repressive, innovative and conservative force.

Is “taste” a mere personal and cultural issue? Why did musical taste matter to Chinese state authorities? How did taste be shaped and reshaped? In the late seventeenth to eighteenth century, while China was the wheel of the global market, the lower Yangzi delta (Jiangnan) was China’s commercial hub and the site of the most productive qin-zither music publishing—both fueled by wealthy merchant families whom the state highly financially relied on. Members of the Jiangnan merchant families arose as new cultural elites through their unprecedented music publications and their unparalleled success in political networking. Meanwhile, their diverse, and even conflicting, reinvented perceptions of high musical taste incited not only zestful responses from their contemporaries but also unusual reactions from the Qing emperors themselves. The discussions on musical taste were, in fact, the convergent point of political, commercial, and cultural powers in which we see how a musical instrument can be simultaneously a revolutionary and repressive, innovative and conservative force that shaped the discourse of early-modern high and low culture and even, the present-day perception of “Chinese tradition.”

You are currently planning a research trip to the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the University Archives in the University of Hong Kong. Could you share a little about your process as an archival researcher? What sorts of documents are you hoping to uncover? How do you approach preliminary materials from the 18th century?

Yes, I have finally booked my flight to Hong Kong this December! This is really a long wait. On the one hand, archival research is a treasure hunt, and you never know what awaits you; on the other, primary sources are silent teachers who may also surprisingly alter your initial thoughts and presumptions. Since early-modern qin-zither music shows a robust geopolitical feature, I hope to explore the musical sphere in the Lingnan region—their discussions on high and low musical culture and their social and political networking. In doing so, I seek to broaden the current horizon that primarily focuses on the prosperous Jiangnan region to a politically and culturally marginal area in the Qing empire.

In order to revisit the interplay of the Qing state and Chinese elite, as well as early-modern Chinese urban life and culture, I categorize primary sources into four categories. The first category is the documents regarding Qing-era qin-zither studies and compositions. The second category is the government documents to surface the state and local government’s policies, particularly on music and culture. The third category is officials and elite’s biography and individual letters for observing the political and social networking related to qin-zither scholars. And the fourth category is the reprint records on the material heritage of the qin-zither body and urban life.

As someone who studies the cultural reception of a musical instrument, I’m wondering about your own connection to the qin-zither. How do you respond to music played on this instrument? How does your own aesthetic experience of the instrument relate to your research work?

Whether achievable and valid, I hope my studies can liberate Chinese traditional music from elitist hierarchization: Let music be music!

I have learned and played this instrument for more than a decade since my college years. To me, playing qin-zither is a meditating communion with the universe and my inner self. For its peculiar tones and melody of tranquility and serenity, I personally love it more than all other instruments I learned, namely erhu (Chinese fiddle), piano, and Chinese bamboo flute. However, do timbre and musical features alone qualify the self-evident ideology in the present-day academia and public media that only the qin-zither enjoys the most prestigious status as the Chinese traditional high culture? Meanwhile, other Chinese musical instruments—flute, pipa-lute and zheng-zither in particular—are considered vernacular, vulgar, and low. But why have musical instruments been placed in a hierarchy by which also hierarchized social groups and people who play those instruments? All these questions have plagued my mind for a long while. Whether achievable and valid, I hope my studies can liberate Chinese traditional music from elitist hierarchization: Let music be music!

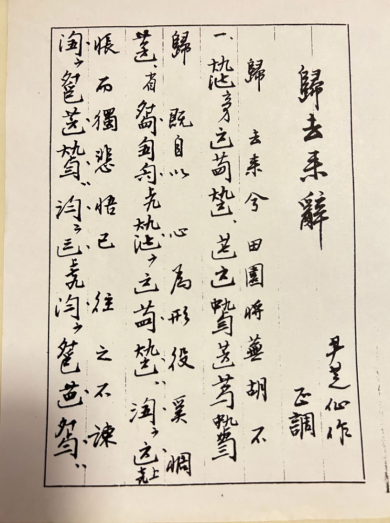

Manning Chan plays “A Serene Night” on her qin-zither.

Finally, what is your favorite place on the UCSC campus?

My favorite place is the little hill between Rachel Carson and Oak College, near the West remote parking lot. Climbing up to the hill and seating on the wooden bench, overseeing the long seashore and seasonal color-changed grassland, became my, almost, daily habit. That beyond words can tell how relaxing and rejuvenating it is, when you feel every breath, listen to the gentle breeze, while immersed in the peaceful sunset ambience. Highly recommended!

Banner Image: Manning Chan’s qin-zither.