Nathan Osorio is a PhD candidate in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. His creative/critical dissertation explores Latinx decolonial poetics alongside a creative poetry performance manual for cultural production. In January, we learned more about Osorio’s ongoing writing and public humanities work. Osorio received a 2022-2023 THI Year Long Public Fellowship to work with UC Press, a forward-thinking scholarly publisher “committed to influencing public discourse and challenging the status quo.” We discussed Osorio’s critical and creative approaches to decoloniality, the vitality of transborder collaboration, and the potential of a communal ethos in the publishing industry.

Nathan Osorio is a PhD candidate in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. His creative/critical dissertation explores Latinx decolonial poetics alongside a creative poetry performance manual for cultural production. In January, we learned more about Osorio’s ongoing writing and public humanities work. Osorio received a 2022-2023 THI Year Long Public Fellowship to work with UC Press, a forward-thinking scholarly publisher “committed to influencing public discourse and challenging the status quo.” We discussed Osorio’s critical and creative approaches to decoloniality, the vitality of transborder collaboration, and the potential of a communal ethos in the publishing industry.

Hi Nathan! Thanks for chatting with us about your public fellowship work and your ongoing research and writing projects. To begin, could you give us a general synopsis of your dissertation project?

Hi Kirstin! Thank you for your thoughtful questions and for the opportunity to share a little about my research. My dissertation, currently titled, Borderland Vitality: Transdisciplinary Decolonial Poetics as Resistance, is one part critical dissertation on Latinx decolonial poetics and another part creative community-facing manual for decolonial cultural production and public learning. As a Literature PhD candidate in the Critical and Creative Concentration, my project is unique in that it intertwines “traditional” critical dissertation writing grounded in theory and research with performance and creative writing. The issue at the center of my dissertation is how to best understand the poetic artifacts (lyrics, prose, performances, installations, labor actions, and translations) produced in response to collective and personal histories where the open wound of the 1492 colonial encounter is active, urgently reshaping the region that we recognize today as Latin America and those who identify as Latino/a/e/x. Examples of these histories include the deportation of my father in the 1980s or the generational forgetting spurred on by U.S.-backed civil unrest in Central America. I am particularly interested in the role language plays in processing examples like these.

Your project pays particular attention to the ways decolonial poetics resists or even exceeds traditional (Western/white/canonical) notions of ‘text’. How does this kind of linguistic subversion (or expansion) resist coloniality?

As a Latinx poet and scholar, I’m struck by how a key weapon in the colonization of the Américas was the monopolistic implementation of a graphical textual language, a semiotic tool that violently alienated Indigenous communities on their own land. U.S.-Eurocentric textuality and forms are tools of coloniality that work to maintain order, control, and racial hierarchies. Despite these overwhelming efforts which have endured generations, texts often become cultural borderlands where contact between the “other” and the West continues to play out in conflict. In my dissertation, I explore the work of five contemporary Latinx poets and artists whose creative practices push western textual forms beyond their limits by wielding multimodal and transdisciplinary methods that challenge our expectations. By breaking open western forms and relationships to textuality, the artists in my dissertation unsettle the building blocks of the colonial archive while illuminating complex relationships to conceptual categories key to understanding life within coloniality.

Their examination of these categories highlights things like the incompatibility of the western archive for BIPOC artists, alternative relationships to language that better represent lived experiences not faithfully rendered in the West, and methodologies for the production and circulation of work built alongside insurgent collectives. These artists present to us other modes of feeling, thinking, and being with our bodies in the Américas that trouble how we understand and interact with coloniality. I think of the poet Anthony Cody, whose interactive poems require readings performed by multiple readers at once and blend elements of visual collage and archival research to unearth histories of lynching Mexicans in Gold Rush California. For Cody, the multimodal poem is an invitation to tear away at the closed, controlled, and contained margins that textual language defends in some white, U.S.-Eurocentric historical accounts. I also think of Natalie Diaz’s work on the Colorado River in the wake of the 2017 Dakota Access Pipeline Protests at Standing Rock. In her poem, “exhibits from The American Water Museum,” Diaz creates a lyrical museum that highlights the way the U.S. government has and continues to destroy water access for poor and Indigenous communities throughout the country. By invoking the form of a museum catalogue and speaking directly to the reader, Diaz invites us to imagine her poem as a physical museum space where she as a Mojave poet guides us through a counter-history.

Your dissertation argues that decolonial art practices serve as sites for both “resistance” and “vitality.” I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about how, for you, these two concepts co-mingle, both as intellectual frameworks, and also as material conditions of life at/near/across the border.

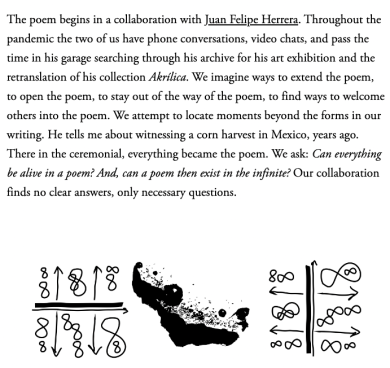

Excerpt from Anthony Cody’s “HomeHumanMachineFailureSpiral”

The cultural productions I research are often built from processing the back-and-forth crossings that happen literally, and in the colonial legacies that shape lived experiences within and across generations. I believe that they insist we should tend to more than just the sorrow, longing, and loss rendered on either side of or at the very center of the border. In spaces like libraries, art collections, and museums, the colonial archive can try to dilute and deaden borderland histories. In light of this, many of the artists I research remind me that their work resists being contained to a bibliographic entry. Instead, the work lives a fuller life as a generative site where things like community, growth, joy, love, and sex are tools towards liberation from coloniality.

I’ve found vitality and resistance useful as intellectual frameworks that keep the aesthetic and affectual possibilities of my research and poetry open. These frameworks guide my reading, keeping my understanding of the poetry nuanced and even sometimes beyond my own reach. They also ensure that my analysis of the work can’t be pulled in one direction or another like a binary, so that the work can continue surprising me—and hopefully other readers—by using vitality to access the pain of a long and at times seemingly endless resistance.

Your dissertation includes what you call a “poetry performance manual” that invites participants to produce creative writing and performances to enact the decolonial practices you outline in the critical portion of your dissertation. Can you share more about how you arrived at this exciting, participatory, genre-expansive form? Why is it important in your work to make space for this kind of artistic and intellectual collaboration?

As a result, the dissertation is an example of resistance to violent and silencing ways of knowing while also enacting a vitality that renews transborder relationships and community.

In researching decolonial poetics through the guise of a dissertation in a PhD program in the U.S., I have the opportunity to work through a productive tension that challenges me to be mindful not to contradict myself. This tension encourages me to trouble the dissertation as my primary formal instrument of analysis. Thanks to the guidance of my dissertation committee, I was motivated to take on a less than conventional dissertation form, which like the artists I’m studying, feels more honest to my lived experience as a poet and first-generation Latinx scholar.

I could not have reached this advanced degree of study without my community and family, so I’m excited that the poetry performance manual is being created in collaboration with two student groups in Los Angeles, California, where I was born and raised, and in Acatlán de Osorio, Puebla, México, where my father was born and raised. The voices and fingerprints of the student participants from these regions will exist throughout the final manual. In that way, it’s a form of pedagogy built by and meant to serve communities historically left out from the academy. My work then enacts that same unsettling of forms to imagine other relationships to knowledge production. As a result, the dissertation is an example of resistance to violent and silencing ways of knowing while also enacting a vitality that renews transborder relationships and community.

This year, you are working as the Year Long Public Fellow with UC Press. Can you share what drew you to this position and what you spend the majority of your time working on?

Still from my 2019 Poetry Performance “Altar/ando”

When I was a kid, my father came home one day from working at the grocery store with a cloth-bound copy of The Hobbit that his coworker had given him. I still wonder how a 1937 British fantasy novel about dragons and an unlikely crew of heroes ended up in an L.A. grocery store breakroom where immigrant workers rested from hours of unloading cases of soap and frozen meat. Since my dad gave me that book, I’ve been fascinated by how and what knowledge is produced and circulated. The mission of UC Press–to amplify bold, diverse perspectives and inspire critical thought and action–drew me to apply to the position to better understand how university presses curate their lists, acquire books, and participate in the production of knowledge that is so central to my research. The staff members I’ve worked with on the Acquisitions Editorial team at UC Press have been very generous mentors. They’ve given me opportunities to conduct research that impacts what scholars and topics they might consider for publication in the future. I’ve developed scouting lists for prospective scholars in feminist studies, criminology, law, economics, and technology studies.

You have said that you see the act of publishing as a “moment of community.” What do you mean by this? What kinds of community do you see forming in your position at UC Press?

To me, watching so many people come together at UC Press to create a book is a powerful example of vitality.

In my experiences as a writing instructor, an editor, and now as a Fellow at UC Press, I’m always struck by the myth of the cloistered artist or the solitary scholar. I’ve learned that this isn’t a complete portrait or depiction of what it takes for a cultural production to reach its audience. For the book to come to life, it demands not only an audience but careful bookmakers who are technicians and craftspeople in their own right. I experience moments of community in different places at UC Press, and I’m particularly excited by the emerging cohorts of editorial assistants and associate editors at the press who, under the guidance of senior editors, are encouraged to bring their ideas to the page and to readers everywhere through free, open access technologies. To me, watching so many people come together at UC Press to create a book is a powerful example of vitality. It brings to mind the small poetry workshop where students work together to produce a community chapbook because they believe that their contribution might make our world a more livable place.

Banner Photo: Still from the reading and performance Words for Water: Stories and Songs of Strength by Native Women featuring Natalie Diaz, Jennifer Foerster, Joy Harjo, Toni Jensen, Layli Long Solider, Deborah Miranda, and Laura Ortman and contributions by Heid E. Erdrich and Louise Erdrich.