Public Fellow Spotlight: Eric Sneathen, Literature Doctoral Candidate

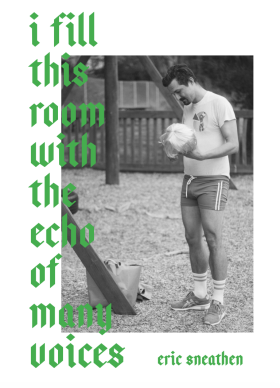

Eric Sneathen is a sixth-year PhD Candidate in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. As a 2019-2020 THI Public Fellow, Eric worked in the archives of the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. He is a poet and the author of Snail Poems (Krupskaya, 2016) and the chapbook I Fill This Room with the Echo of Many Voices (eyelet press, 2019).

THI spoke with Eric about his work for the archives on the ACT UP Oral History Project, time spent listening to audio cassettes “in the (windowless) basement of a building downtown” (“perfect for nerdy introverts who love to be meticulous”), and the similarities between poetry and scholarship (“no one’s going to give you permission to do the work that needs to be done”).

You’re working in the archives of the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco this year as a Public Fellow. Can you tell us about this role? How has your work with the Society dovetailed with, enhanced, or connected to your own academic research?

Since September, I have been working in the Dr. John P. De Cecco Archives and Special Collections of the GLBT Historical Society, which has meant, mostly, surveying and managing their collection of hundreds of oral history interviews. There’s a gigantic filing cabinet filled with hundreds of those old audio cassette tapes, and it’s my job to keep them in order, to make sure there’s a record for each interview, to identify whether or not there’s a transcript, and to locate any extant digital versions of the interviews and/or transcripts. Including the oral histories undertaken by Allan Bérubé for his groundbreaking history of gay men and women during World War II (Coming Out Under Fire), these cassette tapes have been accumulated over decades and represent an idiosyncratic yet expansive account of the sexual politics and cultures of North America.

I didn’t enter graduate school thinking I would be working with archives. In a way, I wish I didn’t have to work with archives, even though I love doing so. I’ve been surprised to find out how pernicious, how enduring the effects of homophobia have been, that the study of LGBTQ+ poetry, especially of San Francisco, one its major sources, requires the use of archives; tucked away in neat boxes in institutions across the country, are some of the only bits of correspondence that speak to author’s intentions, political commitments, personal ephemera—the biographical and historical detail that might restore significance (if that’s possible) to these works of art. One thing about being a poet that’s similar to being a scholar, I’ve found at least, is that no one’s going to give you permission to do the work that needs to be done. Encouragement exists, but that permission doesn’t exist—the poetry that needs to be written, the scholarship that needs to be undertaken, it has to be created, it has to be seized by those who are inspired, or who are fortunate enough to have access. Through my connections to a living tradition of poets and my years at UC Santa Cruz especially, I think I’ve had a little bit of both, and I’m so grateful.

Can you tell us about the specifics of your role in the archives? Do you spend a lot of time with the materials?

The poetry that needs to be written, the scholarship that needs to be undertaken, it has to be created, it has to be seized by those who are inspired, or who are fortunate enough to have access.

I’ve had a lot of fun (and learned a lot from) listening to as many of the tapes as I can, though it seems I’ve hardly made a dent in the collection overall. I did get to listen to Sam Steward (aka Phil Andros) talk about his experiences with Alfred Kinsey, a recording that featured what seemed like dozens of clocks going off at irregular intervals. As a poet and a student of literature, it’s been interesting to see how writers have been called upon to do historical work—Thom Gunn talking about artist Chuck Arnett, John Coriolan enthusing about bathhouses long closed, acquaintances remembering the radical, bookseller, and poet Tede Matthews.

I’ve also been able to find some tapes that appeared to be missing or misplaced. How gratifying is that? Even if the recording isn’t the best, each interview is unique—from the relationship between the interviewer and interviewee down to the quality of voice—capturing something precise and significant about the historical situation of speaking to one another, no matter where the conversation goes.

You worked with the GLBT Historical Society over the summer of 2018 as a THI Summer Public Fellow, and then extended your fellowship into the full academic year. Can you talk about the differences between the summer position and the year-long one?

I guess it’s easiest to say that my work for the Historical Society over the past year, surveying the entirety of the oral history collection, is an expanded version of my summer work on the ACT UP oral history project. But the projects are distinct in that the ACT UP oral history project taught me a lot about project management, which is more collaborative and public-facing, while the year-long fellowship was focused on archives management. People might be familiar with the GLBT History Museum in the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco; the Historical Society’s archives, however, are located in the (windowless) basement of a building downtown. It’s much less “public-facing” and more, well, perfect for nerdy introverts who love to be meticulous. As that kind of nerd, I feel perfectly at ease surrounded by silent boxes. I was a page, as an undergraduate, at UC Davis’s Shields Library for five years after all.

When I worked for the Historical Society during the summer, I was tasked with producing educational materials that K-12 educators might use as part of their classroom curricula. As soon as I got to work, however, a new opportunity emerged: their ACT UP Oral History Project needed a new director. I was really excited about the position because the history of ACT UP (and AIDS activism in San Francisco) complements and is quite distinct from the history of ACT UP in New York.

Like New York, San Francisco was devastated by the epidemic and there was an urgent need to mobilize an immediate response to the crisis. ACT UP originated in New York City and there were several chapters of ACT UP in the San Francisco Bay Area—notably ACT UP/San Francisco, and, beginning in 1990, ACT UP/Golden Gate. But the name of ACT UP/San Francisco obscures the origins of the group in its previous iterations—AIDS Action Pledge and Citizens for Medical Justice—which were inspired by the Central American solidarity movement. (See Emily Hobson’s Lavender and Red for more.) The response to the AIDS crisis in San Francisco was decidedly West Coast—early ACT UP meetings were held in circles and used consensus; there were also the Shanti Project, the Healing Alternatives Foundation, the NAMES Project, Enola Gay’s Blood and Money ritual, Maitri Hospice at the Hartford Street Zen Center, Project Inform, and the iconic (and only) blockade of the Golden Gate Bridge by SANOE (Stop AIDS Now Or Else). But actually, when I first came to the project, I was less motivated to learn about what made the AIDS activism of San Francisco unique or different than, say, that of New York, and more interested to learn about how AIDS activism had been a part of the lives of my friends, fellow poets, and mentors.

You’re also a poet. What can you tell us about the poetics that your own work embodies? How does queerness feature as a theme in your work? Has working at the GLBT Historical Society shaped or changed your own poetry?

I’m blushing a bit, but yes last year my fellow poet-friends, Sophie Dahlin and Jacob Kahn at eyelet press, published a new chapbook of mine with a long title: I Fill This Room with the Echo of Many Voices. The title is borrowed from Derek Jarman’s film Blue, and it describes my method of engaging with a speculative archive of Gaétan Dugas, whom journalist Randy Shilts falsely identified as the so-called “Patient Zero” of the AIDS epidemic in North America. Basically, using a version of the cut-up method popularized by William Burroughs, I generated sonnets from this “archive,” which included text from Shilts’s And the Band Played On and anything else I could find that talked about this unknowable individual, who had received such judgment and whose actual historical being has been overshadowed by the mythology that has been wrapped around him.

I’m blushing a bit, but yes last year my fellow poet-friends, Sophie Dahlin and Jacob Kahn at eyelet press, published a new chapbook of mine with a long title: I Fill This Room with the Echo of Many Voices. The title is borrowed from Derek Jarman’s film Blue, and it describes my method of engaging with a speculative archive of Gaétan Dugas, whom journalist Randy Shilts falsely identified as the so-called “Patient Zero” of the AIDS epidemic in North America. Basically, using a version of the cut-up method popularized by William Burroughs, I generated sonnets from this “archive,” which included text from Shilts’s And the Band Played On and anything else I could find that talked about this unknowable individual, who had received such judgment and whose actual historical being has been overshadowed by the mythology that has been wrapped around him.

I’m now working on the second half of that poetry manuscript, turning to face Randy Shilts. The archives of the GLBT Historical Society hold some of Shilts’s materials, including two items that have been especially interesting to me, one written before he became a famous journalist, another written before his death from AIDS-related illness. I’m thinking of calling it “The Bronze Age,” and using an epigraph from Emily Wilson’s translation of Homer’s The Odyssey. In one scene of The Odyssey, Helen offers her guests a drug so powerful it will remove all worry from their minds, “even / if soldiers kill her brother or her darling / son with bronze spears before her very eyes.”

Why read (or write) a book about AIDS?

I’m especially interested in what it means to be a younger person writing about the AIDS epidemic in the age of PrEP and Truvada. Listening to the voices of those who died during the epidemic, reading their poems and stories, not being able to converse with these people or share space with them, I experience the great loss of the epidemic constantly, though, certainly, my emotional relationship to that loss is distinct from that of others. Does that distinction afford me access to a different kind of art?

With the current COVID-19 crisis, a lot of work has moved online. Have you found a way to transition your role at the Society remotely?

Unfortunately, the archives are closed for now, so I had to stop my work rather abruptly. Still, the GLBT Historical Society is moving forward with online exhibits. They recently launched an online version of their exhibit Performance, Protest, & Politics: The Art of Gilbert Baker. Soon we will be launching an online exhibit focusing on AIDS treatment activism, incorporating some clips from the ACT UP Oral History Project. This exhibit will look at the organizations and actions that dedicated themselves to the treatment side of the AIDS epidemic—getting drugs into bodies, demanding a seat at the table with pharmaceutical companies, and volunteering for clinical trials. Furthermore, we’re hoping to finish the first phase of the ACT UP Oral History Project in the coming months, when the bulk of the interviews will be made available online. It’s been a lot less time in an enchanting basement, much more time creating excel spreadsheets and petting my cat as files download.

Looking forward, how does your work in the Society relate to your professional goals, be they academic, non-academic, literary, or otherwise?

I feel like I’ve become a part of the great effort to transmit the vapors of history from one living body to the next, so that they might be made newly meaningful to someone else.

Looking toward the future, what a horror! But I hope to be able to work in a capacity that allows me to use the expertise I’ve accumulated during my graduate studies. Even if I can’t remember every turn of gossip, I feel like I’ve become a part of the great effort to transmit the vapors of history from one living body to the next, so that they might be made newly meaningful to someone else. Maybe that will be an academic job. But I think the future’s elsewhere. There must be some poem about it, perhaps neatly filed away inside a seemingly un-marvelous brown cardboard box.