Graduate Profile: Morgan Gates, Literature Doctoral Student

Morgan Gates is a PhD Student in the Literature Department at UC Santa Cruz. She specializes in twentieth-century American literature with attention to book history and auditory culture. Gates investigates the ways sound is used, represented, and theorized in literature and American culture – bringing together methods and materials from sound studies and literary studies.

In February, we sat down with Gates to learn more about her current research and experiences as a THI fellow. Last summer, she was selected as a THI Summer Research Fellow and used her support to engage with key archival collections. We discussed the relationship her work explores between literature and sound, her experience working with archives in various capacities, and staying dynamic in a time of pandemic.

Thanks for taking the time to speak with us Morgan! To help ground our conversation, would you mind giving us an overview of your research interests? How do you think about your scholarship?

Thanks for the opportunity to share! I’m interested in 20th century U.S. American literature and culture, particularly the intersection of literary enterprises and aural culture. My research examines the ways that Americans use and are represented through sounds or sound practices in literary texts to consider and contest dominant narratives within American culture, particularly narratives of race, gender, and class.

I’ve lately gravitated towards studying representations of music or thinking about American music and literature. But research in literary sound can also mean thinking about all kinds of sounds: noise, silence, animal sounds, urban sounds, all interesting jumping off points. I am not a musician (people always ask me that!) but I don’t think I know anybody who doesn’t love music, who doesn’t integrate it into their life in deeply personal ways, or who doesn’t at least think about it from time to time. So it’s my hope that my scholarship will offer new perspectives on what we listen to and how we listen by listening back, and I hope it will motivate folks to explore literature as a means to enrich our relationships with music and sound.

Listening has become a keyword for sound practices in everything I do as a scholar. But more broadly I think it is something to be taken seriously and rethought, especially in the present moment. From just about every angle, this past year has been a lesson in the necessity for better listening practices. Black / Brown / Indigenous people of color need to be listened to, not just heard; epidemiologists, environmental scientists, graduate students, children, healthcare workers, artists all need to be listened to, not just heard.

It seems like a big part of your research revolves around auditory culture. What would you like us to know about this component of your work? What does it offer us in thinking about American literature?

It’s not just about the sound but what kinds of meanings it makes, who gets represented, who gets listened to, who makes what sound, and how they identify with these sounds.

Literature is such a visual medium. For modern readers, it’s synonymous with the book. Because we so often encounter literature in its print form, it’s easy to overlook that we can turn our ears to it and what we learn from doing so. One question that interests me, for example, is what literature records and why. For my work, listening to 20th century literature begins with listening back. In the late 1800s, American writers were really interested in capturing the sounds of voices, regional dialect, you know, Mark Twain, George Washington Cable, Joel Chandler Harris. So that’s one way of listening to literature.

But it’s more than that. Literature represents sound in multiple ways. My own investigations of sound have allowed me to ask a lot of different questions of a literary work. For example, if I am taking silence as a sound for investigation, I’ve asked questions about the material body of a book by looking at its silent pages. I’ve analyzed illustrations of scenes of silence for how they suggest structures of power absent in a narrative, and in narratives silences I’ve discovered powerful anti-authoritarian acts of refusal to sound out. So it’s not just about the sound but what kinds of meanings it makes, who gets represented, who gets listened to, who makes what sound, and how they identify with these sounds. So, sound study is really generative for thinking about American literature or any literature in a lot of ways.

You’ve done a lot of work in various archival bodies, including processing collections through the CART Program and designing exhibitions around material. What role does working with these sorts of materials play in your work and thought? And how do you think about your relationship to archives more generally?

Yes! I worked with the lovely CART mentors and fellows to process a huge archive, The Trianon Press Archive. In operation from the 1950s-1980s, Trianon was a fine arts press based in Paris. The Press was run by Arnold Fawcus, a former combat ski-instructor and counter espionage intelligence officer turned fine art book-maker. The Press is best known for their work under the William Blake Trust making the highest quality facsimiles of the catalogue of Blake’s illuminated prints – from which Trianon’s prints are virtually indistinguishable from the Blake originals, save for watermarks. I was really glad to be a part of the project, and though I did a lot of work processing over a thousand objects and documents, I think my most personal contribution and point of pride was lobbying for the digitization of three audio objects in the collection.

I love things, objects, stuff. I feel a strong sense of wonder and magic about material objects and an actual joy in discovering overlooked treasures. I am inspired by the ways that finding an object can connect one to the other people who have handled it, to the places an object has been, to the times it has managed to survive, and to the story it tells.

Working with archives gives me a lot of pleasure, and I think it’s really important to allow for pleasure in any work that we do. A lot of times, it’s hard for me to find a starting point with research or different projects, but what I have found that works for me is to just start looking, let something strike me, and follow it. So far this has been really productive (or at least fun!).

As a THI Summer Research Fellow, last summer you were slated to work with the Frank Kofsky Archives. Can you tell us about the importance of these archives to your work? What sort of changes did COVID force into your plans?

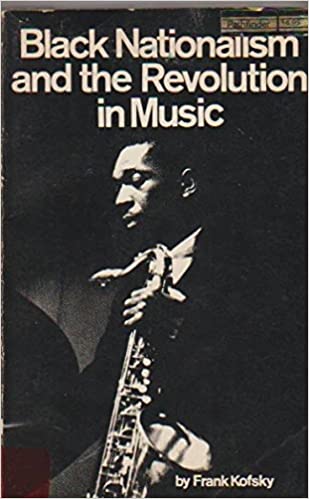

My initial plan for the THI Summer Research Fellowship was to survey the Frank Kofsky Archives and listen to its unique set of interviews with jazz musicians of the 1960s. Frank Kofsky was an author, scholar, photographer, and historian of jazz in the post-war period. His writing exemplifies who he was—outspoken, pro-Black, argumentative, an activist for social justice who was deeply committed to his field. Much of his writing exposed, critiqued, and aimed to dismantle white supremacist structures in the jazz industry and its criticism (not to mention academia). Though he’s not without critique, nor is his writing, his work is as relevant as ever for its amplification of Black sound and voices in the academy and for its militant attitude toward systemic racism.

Unfortunately, I had to make do with the limited access to archives because of COVID. Luckily, I have his books, I have some transcripts from the interviews, and at least one interview (with John Coltrane) is available online. So even though my plan was undercut, I was still able to get to something interesting. Kofsky often asked musicians about how Black nationalism related to musical practice, how musicians reflected on listening practices in the space of the jazz club, and how they related their music to the war in Vietnam. Though I find all of these questions interesting, it is the last one (also the one I would not have expected to be my interest!) that has been taking shape for me as most valuable to my research. I think a lot of writing on music and the war in Vietnam tends to focus on pop and rock music brought there by soldiers or folk musicians as activists on the domestic front. So I was intrigued to think about how Kofsky’s interviews point toward another way of thinking about avant garde jazz, which is often thought of in terms of its relationship to Black liberation in the U.S., not Vietnam. Thinking about American imperialism and its relationship to Black sound, I have arrived at a new question: how does listening represent a collapsing of the foreign and domestic in literature? I was able to give name to something I had been swirling around, this relationship between the foreign and domestic in literary representations of listening. There’s several literary texts representing the Haitian revolution for which this question is especially productive.

And while I wasn’t able to accomplish quite as much as I had hoped for with Kofsky’s archives themselves, I did use the fellowship to pursue archival listening by engaging online resources: the Library of Congress National Jukebox and the UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive. Both are great, but I really, really, love what UCSB has put together. I’d definitely recommend checking it out. There’s all this great old-timey music. From these archives, I developed a syllabus for a class on “Literature and the Arts” that will focus on listening, music, and African American literature. The class will build skills in listening and analysis of listening—teaching us to listen better, then it will take music as a sound to be listened to in literature and in audio archives. It pairs audio archives with literary texts to offer students (and myself) a chance to investigate the Black roots of sound culture in the U.S. and its deep entanglement with literary figures and enterprises in the early 20th-century.

I spent a lot of time with Zora Neale Hurston’s 1930s recordings for the Federal Writer’s Project (WPA) program to think about listening as a method for preserving folk culture, tales, and voices, a practice that in turn informed Hurston’s literary achievements. This was a joy because, first of all, Hurston is an amazing singer! But her recordings also tell us something about how listening is an ethical method for study, for learning from communities that one may not exactly be a part, and in supporting those communities. In the recording of “Halimuhfack,” a bawdy jook tune, she recites the tune and explains her method of learning through listening. Pending final approval, the course should be offered in Spring 2022!

This year, you’ve been a THI Public Fellow with the Museum of Art and History. What have you been working on in this capacity? And how has the particular circumstances we’ve faced this year shaped that experience?

I’ve been busy! Over the summer I also partnered with the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History by way of the THI Summer Public Fellowship to develop an exhibit on local history. The exhibit, Do You Know My Name? Sharing the Stories of Santa Cruzans, tells the stories of the not famous and not wealthy people who have lived in the region we now recognize as Santa Cruz County. It tells the stories of Black female surfers, Indigenous activists, teen poets, disability healthcare workers, Latinx community programmers, artists, teachers, students, and more. Telling these stories empowers folks to continue telling their own stories. What I love about the exhibit starts at its title. To ask “Do you know my name?” assumes that one recognizes the value of their name and story, but it is also an invitation to listen and dialogue.

It was a tricky project with a wide scope—so many potential stories to tell, especially given the intent was to be broad and inclusive, geographically, temporally, and through lived experience! I think it hits on a lot of the things typically associated with the idea of Santa Cruz—surfing, redwoods, the university, tourism—while also challenging those tropes.

This project grows out of the Santa Cruz Historical Association Journal Number 8, a publication of the same name. The book and this exhibit is dedicated to the memory of historian Phil Reader, an expert local historian and beloved figure in local history circles. So, I used that book and the spirit of Phil’s work as a starting point. I adapted a few of the articles in the book for the exhibit, but I also used the book to go down a few rabbit holes. For example, there was this lovely picture of the women of the Berry family–in an article that was not about these women but about Black baseball in Santa Cruz. So I got curious about these women and found a blog by one of their descendants, Marissa Arterberry. I reached out to Marissa who was thrilled to share photos and clippings with me so that we could tell the story of Mabel, one of the women in the picture. Reaching out to actual people was a bit intimidating, since my work is usually me and a pile of books. But I have to say the greatest pleasure was in what scared me most at first. The joy that people, like Marissa, expressed in sharing their stories was a real gift.

This project was also impacted by COVID. I had imagined that it was going to be me spending a lot of time in different local historical archives. But switching gears a virtual research plan also led me back home, so to speak. I mined the UCSC Oral History Project and found several stories to amplify. This also turned out nicely because I was able to include audio clips from the interviews and incorporate actual voices. I was grateful to chat with many local historians for leads. The exhibit will go live virtually very soon and I can’t wait to share it. It looks beautiful!

Many thanks to THI, your support has really helped shape my future! I can’t say enough about how great this experience has been. If anyone out there is interested in the Public Fellowships, please let me convince you that you should take the leap!