Graduate Profile: Quyen Pham

Quyen Pham is a graduate student in the Literature Department and received the THI Summer Pathways Fellowship last year. Quyen worked with the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), and we were excited to catch up with them and hear about the experience.

Hi Quyen! Thanks for chatting with us about your THI Summer Pathways Fellowship research. This summer you looked at Theresa Hak Yung Cha’s collections at the Berkelely Art Musuem and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA). Could you start by telling us about Cha, the collection, and how you became interested in working on this research topic?

Absolutely! Thank you for supporting this project. I first read Cha’s Dictee in the context of a seminar on poetry and the devotional mode taught by Jos Charles at UC Riverside. Cha could be considered a canonical author in the field of Asian American studies, but has not been as widely read outside of it. Her kaleidoscopic vision for her book and her rebellious way of using language to reconstitute identity, the body, and Korean history in ways that challenged and excited me like nothing I’d seen before. She primarily worked in film, performance, and visual art, and I felt that her broader artistic practice influenced her bookmaking in a way scholars had not fully explored. This is in part because her body of work resides in the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. While much of the collection has been digitized or republished, nothing can replace the physical experience of seeing her canvases laid out on a table, or watching her 8mm films in their screening room.

This project allowed me to explore how Dictee invokes Cha’s performances and her work across mediums, and more broadly, how a multimodal poetics might unmoor a reader’s orientation toward time and space. Puts one adrift, you might say, in ways that complicate notions of fixedness in texts, places, and self.

It’s really interesting to learn more about your work. Can you tell us about Dictee and your process for analyzing a multi-genre book? What were some of the materials from the archive that have become central to your research?

Dictee was published in 1982 in the midst of the avant-garde art movement and the Asian American political movement and is very much involved in the conversations of the time. It is a famously dense text, opaque in the historical and literary references it evokes, sliding between oral traditions, English, French, and visual language. While I primarily work in literary studies, to study Dictee I relied on Sarah Ahmed’s concept of orientation from her book Queer Phenomenology. That is, I considered what Dictee oriented itself around, how it constructed an imaginary and how its concepts formed spatial relationships to one another.

The archive contained a manuscript of Dictee which Cha had marked up. I was able to see the final changes she made pre-publication, and how precisely she controlled the space on the page and the placement of every word. She also kept some of the originals for the photographs and other materials she reproduced in Dictee. Some were pages she had cut out from another book, a few were postcards she might have come across during her travels, and others were photographs that she made low-resolution scans of. It was very exciting to see the artifacts she was working from and the ways she manipulated them before using them in the finished book.

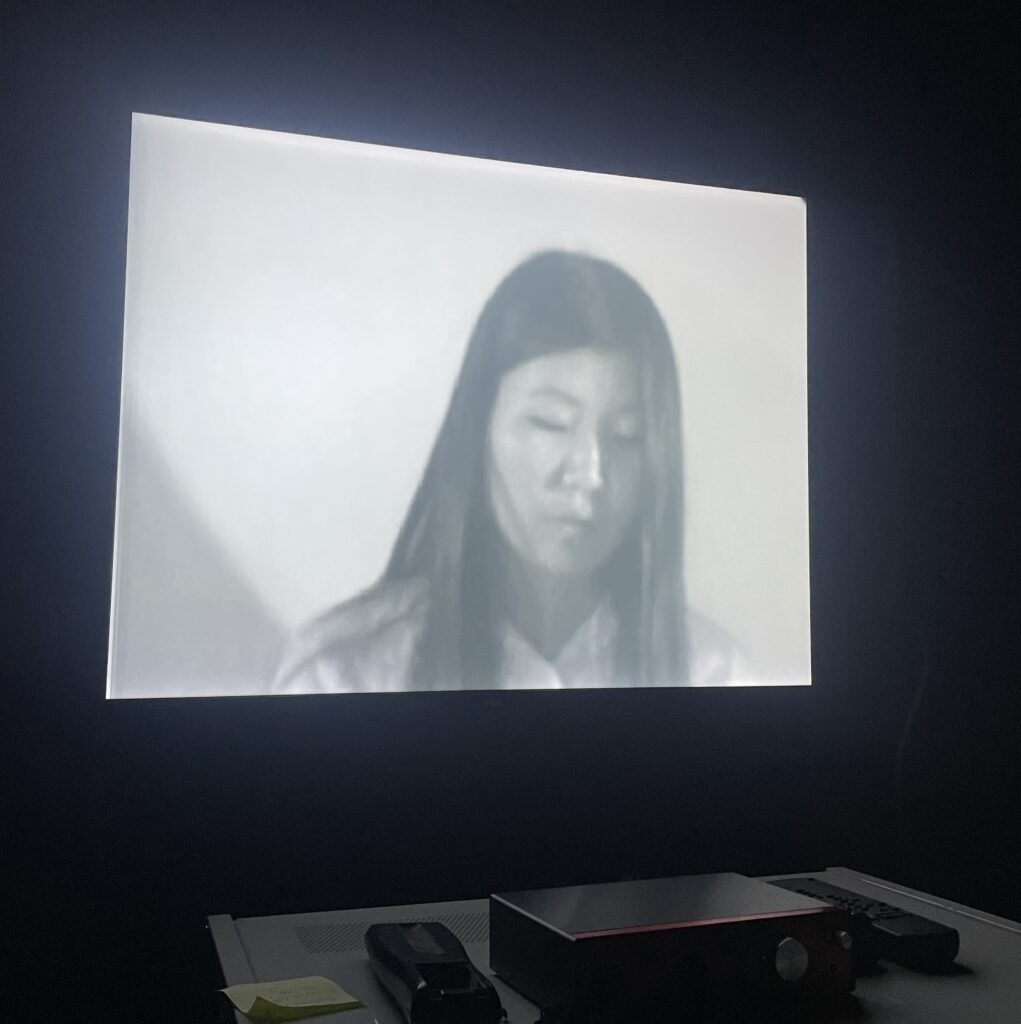

Because Dictee encompasses the difficulty of speech and the possibility of invoking oral language while working in silent mediums, I found a film of one of her performances particularly moving. In it, she is dressed in a white hanbok and lighting candles arranged in several rows. Starting in silence, she then begins to chant in a near-whisper. Her words, indistinguishable, fall out of language. This was an answer to a question I had: how does someone speak without speech? How might Dictee speak?

Even looking through some of her more personal items, like letters, journals, and applications for grants reminded me that, outside of the art she made, she had everyday concerns that I also have, about housing, making a living as an artist, and finding community.

Could you tell us more about your creative writing background and how that influences your approach to your research? Are you also continuing to publish your own creative pieces?

I started taking fiction writing seriously while completing my B.A. in English, which was also when I learned what M.F.A programs are. I needed funding, and Canadian programs couldn’t offer the same financial support I would get if I went to the United States, so I attended UC Riverside on a Fulbright grant to get my M.F.A. in Creative Writing.

Creative writing as a craft is taught completely differently than literary studies. I learned about the mechanics of story, like narrative voice, the management of time within narrative, and story structure, in order to manipulate them, and to see how other writers did. Every week, we would all sit down to comment on one another’s work, and that was how I began to understand the language writers use to critique one another. I also came to understand the artistic and philosophical development of different schools of writing and where I wanted to place my own work in relation to them.

…but of course as a scholar I want my work to change something in the world.

I am still invested in how writers use narrative devices to channel emotional reactions or convey ideas. I still write to and for other writers. I start from a craft question like: “What is the effect of Cha inserting this handwritten letter between these two sections of Dictee?” and build upon my reading with critical frameworks from a variety of fields, including philosophy, cultural studies, and performance studies. I theorize about the text itself, rather than use texts as evidence for particular theoretical arguments.

Right now, I am trying to think through a broader poetics of writing from diaspora, what that historically has meant and how it might evolve. While I have published short stories, I am currently working on a novel as part of my dissertation. I regularly read poetry and prose at open mics around the Bay and internationally to stay in touch with writers external to UCSC.

Alongside your own research this summer, you were a Graduate Student Researcher with Professor Nirvikar Singh on Sikhs in the 21st Century: Remembering the Past, Engaging the Future, a project housed at The Humanities Institute. What was your experience like working on this project and how has it shaped your thinking and interest in public-facing humanities scholarship?

Working with Professor Singh was such a privilege and a gift. My field of scholarship is incredibly niche. There may only be a few hundred people in the world who share my interests, but of course as a scholar I want my work to change something in the world. What often has to happen, then, is a translation of sorts: transforming the research so that more people can engage with it.

I remember a conversation I had with Professor Singh early in the process, in which he shared that this project was really a narrative exercise: putting together a story for and about Sikhs in the contemporary world without compromising on scholarly quality. Put another way, we were performing a narrative synthesis of decades of research on Sikhism, to be made available to the public.

Similarly, writing fiction is how I do public-facing humanities scholarship. This is perhaps more opaque, but every artistic choice I make can be connected to the research I conduct. Sometimes very intentionally, and sometimes subconsciously, but present all the same. I feel the most joyful part of making art is watching people engage with it on their own terms, and find personal meaning in these public artifacts.

Lastly, since moving to Santa Cruz have you found some places on campus or in the community that you love to spend time at? What is one place in Santa Cruz that everyone should visit at least once?

I love walking from Quarry Plaza to McHenry Library over the bridge. It’s a site of transition, this liminal space where you’re suddenly suspended above the ground, beneath a sky that barely peeks through all that green, and surrounded by redwoods. I’ll often just stop there and take a deep breath before continuing on with my day.

In town, everyone needs to go to Bad Animal. The curation of secondhand books there is among the best I have ever seen. Tons of poetry, books-in-translation, philosophy, and theatre, which are usually understocked in even the largest bookstores. Plus, they sell fantastic wine and house Hanloh, my favourite restaurant in Santa Cruz.

Feature Image: Beacon Tower from the Great Wall.