Trung PQ Nguyen is a sixth-year PhD Candidate in the History of Consciousness program at UC Santa Cruz and the recipient of a 2019-2020 THI Summer Dissertation Fellowship. His work examines the visual archive of war in Southeast Asia in the long 1960s, with a particular emphasis on the representation of Vietnamese subjects in U.S. visual culture.

The Humanities Institute spoke with Nguyen this month about his research, PhD scholarship in the time of Covid-19, and the fearlessness of the Humanities at UC Santa Cruz.

Your Summer Dissertation Fellowship supported your project on “Vietnam and Transpacific Imaginaries of Capital and Transition.” Can you tell us a bit about this project, and how you used this Fellowship?

This past summer I used the Fellowship to work on a chapter of my dissertation. I analyzed a film by Santiago Álvarez—a Cuban filmmaker whose work was prolific during the long 60s. He was employed by the Cuban Communist Party and did a lot of film, image, culture, and propaganda work for the Party after the revolution in 1959. As part of that, he made a number of films about Vietnam, around the time of the peak of the Vietnam War.

With the support of the THI Fellowship I delved deeper into the historical context between Santiago Álvarez and his work on Vietnam—in particular, his work 79 Primaveras, (79 Springtimes).

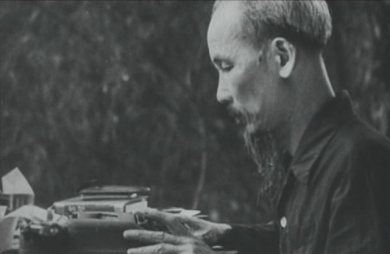

With the support of the THI Fellowship I delved deeper into the historical context between Álvarez and his work on Vietnam—in particular, his work 79 Primaveras, (79 Springtimes), a short film that was a visual eulogy to Hô Chí Minh, the Communist Party leader of North Vietnam at the time. My big questions were: what were the politics of Álvarez examining this historical moment that’s not Cuban (but very much related to Cuba)? What kinds of aesthetics of internationalist solidarity were staged through the film, the process of making it, and its aftermaths? How was race informing the way Álvarez chose to edit, cut, and render aesthetic the different politics he was committed to? I was also interested in the historical repressions that were enacted or staged in the process of making the film.

That sounds like fascinating work. Is your dissertation project as a whole looking at representations of North Vietnam in cinema? Or is last summer’s project one part of a research topic that has a broader scope?

Still from Santiago Álvarez’s “79 Primaveras”

The overarching conversation of my dissertation is about the politics of representation and its limitations. What kinds of historical conditions of possibility are repressed, or mediated, or worked through—consciously or not consciously—through Vietnam as a signifier? Specifically, my research is asking questions about representations of Vietnam throughout the long 60s and its aftermaths. What did Vietnam mean for people? How did it generate and accumulate a revolutionary ethos in the U.S.? What kinds of conversations got subsumed through thinking about Vietnam, and what became manifest? How did Vietnam become a projected semiotic structure for questions that couldn’t be talked about otherwise?

What chapter topics do you explore in your dissertation?

The Vietnam-Cuba conversation is one of the chapters. In other chapters I look at U.S. photojournalism about Vietnam during the War, and how the War precipitated the explosion of the photojournalism industry—and not just due to profit-driven motives, but because the medium became a place to stage questions about citizenship, personhood, decolonization, and what it means to construct or resist a new world order. Another chapter is about the aftermaths of war—how Vietnamese refugees turn back to this history of Vietnam to try to make sense of other ongoing contemporary refugee moments. So it’s about how Vietnamese subjects themselves have used the language and mythos of Vietnam in order to stage their political questions.

I feel our work here at UC Santa Cruz is so theoretically sophisticated and expansive, while at the same time never forgetting the core of the work, which is about how we build a better world.

What drew you to working on this dissertation project? Has it evolved since you enrolled in the History of Consciousness program at UC Santa Cruz?

My project completely changed: I proposed on my application and enrolled with something entirely different. I initially was going to continue what I was going to do in my Masters program at UCLA in Asian American Studies, which was a project about sex and neoliberalism, sex apps, love as a commodity, and the ways that sex gets staged as a digital prosthesis for the intimacy that gets eroded in late capitalism.

I switched gears in my first year. At the core of my initial project on sex and neoliberalism, I was interested in questions about fantasy and the social world. How did people’s attachments to and understandings of intimacy and love shift under certain conditions of capitalism? I switched to my current project on Vietnam because I realized that as I kept going back to this question I would anchor it in my own childhood—how did my family think about intimacy and violence? How do we navigate the total dissolution of a world and otherwise interrupted attachments to a future? These were similar questions across both projects.

I grew up in a refugee, low-income, working class household. My cousins were incarcerated, and there was a lot of violence in my family. In order to make sense of that, my different family members, my mom especially, would tell weird, mythological stories about Vietnam that never made sense to me. My family members told these stories to make sense of what was going on in their lives in the United States. These stories informed how I approach social questions, which led me to see that Vietnam was a bigger influence in my life and in my intellectual trajectory than I had wanted to give it credit for. Plus, there was already so much great work on Vietnamese-American studies; I wanted to see what more could I add.

Thank you for sharing that. I want to also take a moment to acknowledge the current moment we’re going through, and the current context of Covid-19. Given your intellectual area of inquiry, it would be great to hear your reflections on visual representation in the era of the coronavirus crisis, xenophobia, and rising anti-Asian sentiment in the U.S. and globally. Are there any links between the current moment and the Vietnam era in terms of representation?

Still from Santiago Álvarez’s “79 Primaveras”

A big part of my project is to think about how Vietnam, and Vietnamese bodies were the symbol, allegory, and metaphor for “things beyond itself” in the Vietnam War era. The Vietnamese body is the site where where conversations about decolonization, fears about Communism, fears about an alternative world order, or fears about the dying white race, get staged. In U.S. national culture, the Vietnamese body is always attached to the Vietnam War so it’s also the site where those larger questions about U.S. empire waging war get worked out—whether articulable or not. They get worked out on the body because they can’t be articulated through existing frames of knowledge and of words, so they get projected onto the body through violence, or sexual desire, or disgust, or a range of different affects that I’m examining in my dissertation.

As such, I think this pandemic joins up with a lot of outstanding, older discourses about race: fears about “Asian contagion”—or about Asia as an illiberal, backwards site that fails to “civilize”—and fears of deviant reproduction. The pandemic is racializing in many ways – it marks out populations, imbues social meaning onto material surfaces, and relegates these populations to, in Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s terms, premature death. These fears are manifest in the ways you see violence and anti-Asian racism get played out in our social world at the moment.

Similarly, the pandemic has amplified existing racisms– in the U.S., black and brown people (some of whom are Asian, but many more are not) have been disproportionately dying from the virus because these are the bodies you see (and have seen) working the low-wage jobs necessary to uphold life (“essential” work). They are working paycheck-to-paycheck, without adequate healthcare or housing, and are otherwise structurally barred from the conditions of life.

I want to draw on your Ethnic Studies background further here. Do you see the pandemic as primarily exacerbating existing racisms, or are there new forms developing? What role can Humanities scholarship play in addressing this?

The pandemic is also generative of new feelings people have about the dissolution of the promise of being in a social world that takes care of them. Because, fundamentally, receiving that care is no longer possible in the United States, the anger about this gets projected onto Asian bodies or the bodies of other people of color. By the removal of “care” I’m referring to the dismantling of the U.S. social welfare system and reorganization of the labor force geared toward maximized exploitation (and thus maximized profits for the shareholder class) of certain populations from the mid-70’s onward. These are structural inquiries that the Humanities has been working on for decades—and to me, speaks to the importance of Humanities work: to examine how we got to where we are, and to imagine a more expansive future.

The Humanities has been working on [structural inquiries] for decades… This speaks to the importance of Humanities work: to examine how we got to where we are, and to imagine a more expansive future.

How are you coping yourself as a scholar and academic in this moment? How is your work going? Any tips for navigating research and writing in this time period?

I don’t have productive advice. I think we’re in a moment that is uniquely uncertain for more people more than ever. So we can’t really predict what’s going to happen—but we do know that the language of austerity after the pandemic is going to be pervasive in a way we’ve never seen before—at least in our existing lifetimes.

I’ve been on the job market this year. In the last two weeks I’ve gotten four or five emails from tenure-track jobs that I applied to that said, “Hi, we are canceling this job search—good luck with your future.” Jobs across the board are getting canceled, for the Humanities especially. This is not just a reproduction of the 2008 crisis but it’s also a ramping up of it, an exacerbation.

I think it’s important for people in our work to find a way through, and survive, and not feel guilt about that. In my case I’m planning to extend my PhD program for a year, just to have some more options, because we don’t know what’s going to happen after this, and how long we’re in this episode for.

Can you tell us about where you’re at now in your research?

I’m at the end of the dissertation writing process at the moment. The chapters are all drafted, just the introduction and conclusion and incorporating revisions are left to do. There’s an end to the tunnel, it is there.

Congratulations on nearing the end of that tunnel! Looking back, what do you see as some of the highlights from your time at UC Santa Cruz? What have you gotten most out of your time here?

I think that my time at UC Santa Cruz has really taught me the value, importance, and significance of the Humanities. I’ve been able to have so many conversations and grow as a scholar in a way that I couldn’t anywhere else, because of the campus’ incredibly fertile cross-disciplinary, interdisciplinary environment.

At Santa Cruz there’s a fearlessness that I think is really uplifting and worthwhile.

The way that people think in the Humanities at UC Santa Cruz is always at the cutting edge. Whenever I go to different conferences and talk to people from other institutions I realize that I feel our work here at UC Santa Cruz is so theoretically sophisticated and expansive, while at the same time never forgetting the core of the work, which is about how we build a better world. I’m able to have fearless conversations about that in the Humanities here, whereas in other places people may be more bound by disciplinary or professionalizing questions. At Santa Cruz there’s a fearlessness that I think is really uplifting and worthwhile.