Imagination Series: Jennifer Kelly

Jennifer Kelly is Assistant Professor in the Feminist Studies and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies Departments at UC Santa Cruz. Her research broadly engages questions of settler colonialism, U.S. empire, and the fraught politics of both tourism and solidarity. Kelly is currently completing the manuscript for her first book, Invited to Witness: Solidarity Tourism Across Occupied Palestine (Duke University Press, 2023), a multi-sited ethnographic study of solidarity tourism in Palestine that draws from research she completed as a 2012-2013 and 2019-2020 Palestinian American Research Center Fellow. Kelly’s contribution to our 2022 Imagination Series considers how tourism and its accoutrement– guide books, postcards, and tours– allow people to reimagine and subvert dominant understandings of space, place, and history.

Jennifer Kelly is Assistant Professor in the Feminist Studies and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies Departments at UC Santa Cruz. Her research broadly engages questions of settler colonialism, U.S. empire, and the fraught politics of both tourism and solidarity. Kelly is currently completing the manuscript for her first book, Invited to Witness: Solidarity Tourism Across Occupied Palestine (Duke University Press, 2023), a multi-sited ethnographic study of solidarity tourism in Palestine that draws from research she completed as a 2012-2013 and 2019-2020 Palestinian American Research Center Fellow. Kelly’s contribution to our 2022 Imagination Series considers how tourism and its accoutrement– guide books, postcards, and tours– allow people to reimagine and subvert dominant understandings of space, place, and history.

Touring the Colonial Present and Imagining a Decolonized Future

What work can tourism do when it imagines a decolonized future? I have long been preoccupied by this question.

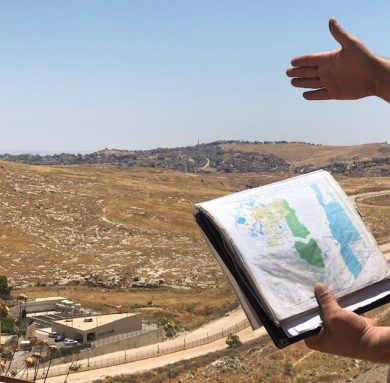

My forthcoming book, Invited to Witness: Solidarity Tourism Across Occupied Palestine, attempts to provide one answer. Invited to Witness is an interdisciplinary ethnographic study of solidarity tourism in Palestine. In it, I situate tourism in Palestine as a crucial subject of study for the Humanities—not only for Palestinian studies but also for feminist studies, critical ethnic studies, and transnational American studies. Analyzing the relationships between race, colonialism, and movement-building in a space where tourism and military occupation often function in tandem, I show Palestinians subject to displacement and exile are reclaiming tourism and its forms to work against colonialism. In this fraught localized political strategy, and emergent industry, Palestinian organizers and guides refashion conventional tourism to the region by extending deliberately truncated invitations to tourists to come to Palestine and witness the effects of Israeli state practice on Palestinian land and lives. I describe this invitation as a genre, marked by the repetition of certain conventions, and I theorize who the invitation is for, what it is meant to do, and how those subjects understood as “toured” redefine the invitation in order to confront and resist settler-colonial contexts that are nowhere near “settled.” I also detail the conditions that have led Palestinians to make their case through solidarity tourism in the first place, describing how tourists travel to Palestine to see the effects of Israeli occupation for themselves despite the volumes of literature Palestinians have produced on their own condition. Tourists, even solidarity tourists, often still need to see it to believe it. And tour guides both work with and reshape this unevenness, cognizant of the ways their narration, and evidence of their displacement, must routinely be corroborated through the figure of the witness. In this way, Invited to Witness shows how Palestinian organizers, under the constraints of military occupation, and in a context in which they do not control their borders or the historical narrative, wrest both the capacity to invite and, in Edward Said’s words, “the permission to narrate” from Israeli control.¹

My next project is Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Palestine, a co-edited volume in the Detours Series at Duke University Press.² In it, we also pose the question “What work can tourism do when it imagines a decolonized future?” but we go on to ask: “How else can one imagine a decolonial “tour” of Palestine?” Co-edited with Lila Sharif (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) and Somdeep Sen (Roskilde University), we are working to curate a volume that shows how Palestinians across Palestine and in the diaspora reshape forms of tourism to their homeland in order to lay a claim to it in the midst of Israel’s settler colonial project. Our volume centers both the decolonial—mourning an occupied Palestine and imagining a liberated one—and the tour—both “touring” a homeland and offering a reader a “tour” of Palestine otherwise obscured by Israel’s tourism of erasure.

For this volume on displacement, anti-colonial forms of rethinking and redistributing space in Palestine, and the role of tourism in both, the contributions we sought with our Call for Papers included anti-colonial tour itineraries, visual cartographies, satiric postcards, artwork, literary prose, poetry, original lyrics, de/anti-colonial culinary narratives, narrative essays, cartoons, and collages.

We received this and more. We received meditations on the intersections of Zionist settler geographies and tourism destinations, enumerating the many ways tourism and colonial land theft operate conterminously. We received analyses of what it means to “tour” Historic Palestine as a Palestinian. We received excavated familial histories of villages. We received decolonial tour itineraries in Palestine, from the perspectives of delegate leaders, tourists, and tour guides. We received recreated, imagined narrations of family members’ exile in 1948. And we received reflections on exiles’ many returns to Palestine—virtual, past, future, imagined.

We also received pieces that imagined a decolonized, never-colonized, liberated, magical, and/or otherworldly Palestine, works that straddle the genres of speculative fiction, fantasy, and political education. We received blueprints for Palestinian tourist destinations in liberated cities, from Gaza to Jerusalem. We received portraits of Palestinians in exile, with musings that imagine never having been exiled. We received analyses of Israel’s ecological degradation in Palestine and visions of the futures of Indigenous plant life. And these are only a fraction of what will appear in the volume.

In terms of genre, we received a pastiche: collage, fiction, photography, poetry, archival ephemera, how-to-manuals, designs, short form essays, beyond. At the same time, we received authors’ and artists’ reflections on process: what it meant to do this work, individually and collaboratively, and how it felt to imagine an otherwise, to mourn one world and craft another.

Given the opportunity to imagine what shape a decolonial tour of Palestine could take, contributors are thus producing meaningful multimodal pieces on their family histories, stories passed down and pieced together, maps of their villages, blueprints of their return, tours of their most beloved places, tours to places they’ve never been allowed to see.

The work of creativity and imagination in the shadow of colonial rule, and the abundance of it archived here, speak to the political need for imagining an otherwise.

The work of creativity and imagination in the shadow of colonial rule, and the abundance of it archived here, speak to the political need for imagining an otherwise. It also speaks to the need for doing so within the Humanities: for carving out the space for and supporting speculative, interdisciplinary, collaborative work across literature, history, art, and beyond—and imagining that work as integral to a decolonizing project.

Because I’ve long worked with the idea of what tourism can do if and when it is pressed into the service of anticolonialism, it is a gift to watch authors, organizers, tour guides, and artists restructure our question(s) about tourism to imagine a liberated Palestine. The shape our volume is taking reveals it as not only a detour itself in its perversion of the guidebook genre—to borrow the formulation of series editors Hōkūlani Aikau and Vernadette Gonzalez—but also a veritable standalone archive comprised of snapshots of Palestine’s past, present, and future. As editors, we are watching that archive take and change shape, an archive of imagination against occupation.

We are working on this volume two years into a deadly and global pandemic, which wholly shut down tourism and revealed stark vaccine apartheid in Palestine. We are also working on this volume on the heels of the Israeli siege on Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan in May 2021—an attack on Jerusalem neighborhoods to make way for the realization of Israel’s biblically inspired King David Park, a theme park for, largely, Christian Zionists.³ In other words, we are doing this work on colonial and anti-colonial tourism in a moment of collective exhaustion. Yet, in issuing a capacious call for contributions, we find ourselves in the process of housing a robust archive of cultural production that both remembers and envisions a Palestine beyond colonial occupation. Responses like those we have received both show the necessary role of the Humanities in diagnosing the colonial present and reflect the precision and care it takes to craft decolonial visions.4 Responses like these also show how, when the space to imagine a decolonized future is provided, and when that imaginative labor is treated as critical liberatory work, an archive will cohere.

Notes

- Said, Edward. “Permission to Narrate.” Journal of Palestine Studies13, No. 3 (Spring, 1984): 27–48.

- Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Palestine is a volume in the Detours series of reinventions of the travel guide at Duke University Press. Duke’s Detours Series, beginning with Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i (2019), co-edited by Hōkūlani Aikau and Vernadette Gonzalez (now Detours series editors), upends the genre of the guidebook by centering Indigenous and place-based knowledge.

- For more on these violent expulsions, see Azad Essa, “Sheikh Jarrah: How the US Media Is Erasing Israel’s Crimes,” Middle East Eye, May 7, 2021. On the specific role of the police in these expulsions, see Oren Ziv, “Israeli Police Determined to Escalate the Violence in Jerusalem,” +972 Magazine, May 7, 2021. For more on organizing against these expulsions that is mindful of Israel’s tourist visions for Sheikh Jarrah, see ““Stop Israel’s Forced Displacement of Palestinians from East Jerusalem!” Everyaction.com, n.d. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- On the colonial present, see Gregory, The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004).

“Touring the Colonial Present and Imagining a Decolonial Future” is part of The Humanities Institute’s 2022 Imagination Series. This series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti in the Humanities community at UC Santa Cruz – each of whom highlight connections between imagination and their work or consider the role of imagination in fashioning new worlds. Throughout Spring quarter, be sure to look for these amazing essays in our weekly newsletter!