Summer Linguistics Trip to Oaxaca, Mexico

Dialog, Research, and Pedagogy in Laxopa, Oaxaca

Associate Professor of Linguistics Maziar Toosarvandani and his students Kelsey Sasaki and Steven Foley reflect on Summer 2019 in Santiago Laxopa, Mexico. Toosarvandani is the Director of the Zapotec Language Project and a co-founder with Pranav Anand of Nido de Lenguas, a THI-supported Project.

This summer, a small team of students and I traveled to Mexico to the small town of Santiago Laxopa, high in the mountains of the Sierra Norte. In this region of Oaxaca, Zapotec is spoken, with each town having its own particular variety. We were there to study the Zapotec variety of Santiago Laxopa, to understand more about it and to speak a little bit of it, too. While it took us a while to get there, by plane and then by car, our connections to Santiago Laxopa originate much closer to home.

The Monterey Bay is home to tens of thousands of people who have immigrated from Oaxaca. Their first languages are indigenous languages — Zapotec, Mixtec, Chatino, and Trique, amongst many others — which they speak alongside English or Spanish. Students and faculty in the Department of Linguistics at UC Santa Cruz have been engaging with this community since 2016, studying these languages and participating in the community’s daily life, primary through the local nonprofit organization Senderos.

In Santiago Laxopa, our host was the Director and Co-Founder of Senderos, Maestra Fe Silva Robles. She welcomed us into her home, fed us delicious Oaxacan food, and introduced us to the town’s president, council, and other residents. During our three weeks there, we carried out a psycholinguistic study exploring how speakers of Zapotec understand sentences as they hear them. Together, PhD students Steven Foley, Jed Pizarro-Guevara, and Kelsey Sasaki and recent linguistics alumni Brianda Caldera and Azusena Orozoco interviewed more than 150 Laxopeños.

This study will create knowledge that informs linguists’ theories of sentence processing, as well as that the community can use. The results will feed into the monthly Zapotec language classes that Maestra Fe teaches in Santa Cruz as part of the Nido de Lenguas initiative, a collaboration between linguists at UCSC and Senderos. Other Nido events include pop-up tables at Senderos’ numerous festivals throughout the year (Día de los Muertos, MLK Day, Guelaguetza) where attendees can learn to speak of a bit of Mixe, Mixtec, or Zapotec by playing fun language games, as well as full-day workshops that provide a more in-depth introduction to a Oaxacan language.

—Maziar Toosarvandani

Kelsey Sasaki, a fifth-year PhD student in Linguistics, reflects on her second summer trip to Laxopa. Sasaki’s own research is in language processing—specifically, the real-time comprehension of syntax and discourse structure. Her work with Santiago Laxopa Zapotec and its speakers also involves language documentation and, as a part of Nido de Lenguas, community education.

Kelsey Sasaki, a fifth-year PhD student in Linguistics, reflects on her second summer trip to Laxopa. Sasaki’s own research is in language processing—specifically, the real-time comprehension of syntax and discourse structure. Her work with Santiago Laxopa Zapotec and its speakers also involves language documentation and, as a part of Nido de Lenguas, community education.

Our second trip to Laxopa for the Zapotec Psycholinguistics Project had two components—the study itself, and English language lessons for the elementary school students. As on my first trip, I was humbled by how generous so many people were to us—sharing their time, language, stories, food, and more.

We began the study in our colleague Fe’s kitchen, watching as participants listened to sentences in Zapotec and chose corresponding pictures on tablets, often with their children looking on curiously as people waiting in line chatted in Zapotec and Spanish. We also spoke with each person in a short sociolinguistic interview, and sometimes informally also. I am very grateful for many of these conversations—through them, I learned a great deal about life in Laxopa and people’s relationships with the languages they speak. One exchange that I found especially moving was with a woman who came in with her young son.

When she was in school, she said, children were punished—often with scoldings, and sometimes with beatings—for speaking Zapotec. So, when she had children herself, she chose not to teach them Zapotec because she hadn’t wanted them to suffer as she had suffered. But lately, she told me, things had changed for the better in Laxopa. Formal education is still in Spanish, but Zapotec is no longer suppressed. In Laxopa’s preschool, the teachers have begun teaching some Zapotec words. With some coaxing, she got her son to count out loud in Zapotec so I could hear. She beamed proudly as she told me that she was teaching him more. She was also glad that she was learning how to write Zapotec—a predominantly oral language—because the preschool teachers had designed written Zapotec homework based on workshops they organized with a group of parents.

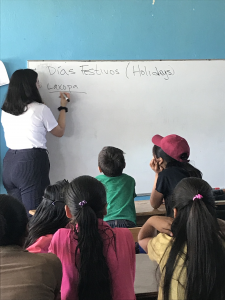

At the elementary school, one of us ran the study while two of us taught English lessons. The lessons were part of our service to the community for welcoming us and allowing us to run the study at the school. This year, we were very lucky to have a curriculum designed by Azusena, one of our undergraduate researchers. Azusena worked in components that encouraged positive attitudes towards Zapotec, such as designing Zapotec superheroes and learning Zapotec words—often from their own classmates—alongside English. Even with summer vacation beckoning, the students were enthusiastic and well-behaved. Some even showed us the notes they had taken during our last visit, and practiced what they remembered with us. After school ended, about 30 students kept coming for summer classes, led by our undergraduate researchers, who the students adored. We continued running the study, this time in the outdoor kitchen area of the school.

All of us were able to speak with other people who shared stories of their experiences with the Zapotec language, the value they place on it, and the efforts they are making and hope to see to ensure that it survives. I feel very grateful that so many Laxopan people have welcomed and supported our project, and am excited to continue working to increase and improve our contributions to their efforts.

Steven Foley, a sixth-year PhD candidate in the department of linguistics, adds his throughts on the research specifics of this year’s trip to Santiago Laxopa. Foley’s broader PhD research into theoretical and experimental syntax focuses on the languages of the Caucasus and Mesoamerica.

Steven Foley, a sixth-year PhD candidate in the department of linguistics, adds his throughts on the research specifics of this year’s trip to Santiago Laxopa. Foley’s broader PhD research into theoretical and experimental syntax focuses on the languages of the Caucasus and Mesoamerica.

As part of a research team from the UCSC linguistics department, this past June I traveled to the small town of Santiago Laxopa, in northern Oaxaca, Mexico. The purpose of our visit was to study Santiago Laxopa Zapotec, or SLZ, an unwritten indigenous language unique to this mountain village. SLZ has many grammatical properties which make it a fertile topic of linguistic research. We were in particular interested in the language’s pronoun system. Like English, the language has pronouns dedicated to human referents (like he/she) and inanimate referents (like it). But unlike English, it also has special pronouns for animals, and for people that are elders or otherwise hold positions of honor in Laxopeño society.

Our research project aimed to understand how SLZ speakers comprehend these four pronoun categories. As language users listen to or read a sentence, we automatically and unconsciously make predictions about how the words we have already heard will relate grammatically to words we have yet to hear. By studying the kinds of linguistic predictions that SLZ speakers make based on the distribution of pronouns of various types across a sentence, we hoped to better understand the universal cognitive mechanisms that guide language comprehension. For example, suppose an SLZ speaker encounters a pronoun early on in a clause, before they can be sure whether it functions as the subject or object of the verb. What grammatical function will they predict the pronoun to have? Our hypothesis was that elder and non-elder human pronouns would be more likely to be assigned the subject role, while animal and inanimate pronouns would be more likely to be assigned the object role. That’s because, more often than not, we humans tend to talk about events in which humans are more prominent and subject-like event participants, and non-humans are the less prominent and more object-like participants.

When she was in school, she said, children were punished—often with scoldings, and sometimes with beatings—for speaking Zapotec.

But just how do you go about tracking the predictions language users make in real time, especially for languages like SLZ that lack a codified writing system? The answer for our research team was to use an experimental methodology known as eye-tracking while listening. Sitting in front of a tablet computer and wearing headphones, a participant in this project would hear a prerecorded sentence of SLZ containing a pronoun. On the screen two illustrations would appear side by side, depicting events described by the sentence’s verb. In one illustration, the referent of the pronoun would have the more prominent subject-like role in the event; in the other, it would have the object-like role. A small device attached to the bottom of the screen would emit infrared light that reflected off the participant’s retinas. Based on the angle of the reflected light, sensors on the device could calculate where on the screen the participant was looking at any given time. Eye movements, it turns out, are very transparent indicators of a comprehender’s incremental understanding of a sentence. Therefore, we could access the predictions SLZ speakers made about the grammatical role of a pronoun based on which illustration they were looking at in any given moment.

Data processing and analysis are still underway, so we cannot yet support or refute our hypothesis. But we count the mere undertaking of this project as a major success. The great majority of experimental linguistic research of this kind has studied large, politically powerful, and mostly grammatically homogeneous languages like English and German. So studying smaller languages like SLZ has two benefits. First, it tests the generality of sentence processing theories, expanding our understanding of what it means to be a language user. Second, it can empower indigenous communities by showing that their language — potentially on the precipice of language endangerment — is just as worthy of study and appreciation as any other. I count myself lucky to have been a part of this unique research project, and look forward to conducting more linguistic work on understudied languages.

—Steven Foley

This Summer 2019 UCSC Linguistics trip to Oaxaca was supported by The Humanities Institute through the Nido de Lenguas Project and the generous support of the Helen and Will Webster Foundation.