Memory Series: Maziar Toosarvandani

Maziar Toosarvandani is Associate Professor of Linguistics and a faculty member of the Zapotec Language Project at UC Santa Cruz. As a syntactician, he seeks to understand what speakers know about the rules of sentence construction in their language. And as a semanticist, he works to understand how they combine this knowledge with what they know about meaning in their language. Toosarvandani’s research focuses on two indigenous languages of North America — Northern Paiute (Numu) and Santiago Laxopa Zapotec (Dille’xhunh)— both endangered and little studied. The latter of these is the focus of his contribution to our 2021 Memory Series. Toosarvandani’s piece explores the relationship between memory and linguistic communities, with special attention to the centrality of this relation for speakers of marginalized languages. In conversation with Fe Silva-Robles (Director and Co-Founder of Senderos), “Remembering Language” suggests that language serves as the root of our understanding of self, and indeed our very being.

Remembering Language

Our memories often speak to us. For me, my recollections of childhood are filled with my grandparents’ voices and the distinctive sounds of their languages.

My mother’s Russian Mennonite parents laced their speech with Plautdietsch, the Low German dialect their ancestors had brought with them to Minnesota. They used it as a private language, mostly to talk about the children. Now, only a few words, like zwieback, knak zoat, and plumamos, survive in my family’s foodways.

I remember my father’s mother almost entirely through her voice, shaped by the Gilaki language of Iran’s Caspian coast. She died when I was eight. In my memories, she is often seated on the floor, a large tray in front of her. She’s cleaning rice or shelling fava beans, and she’s gesturing for me to come sit next to her: Biyə, biyə bənish mibəqəl.

I never learned their languages growing up in Virginia. I spoke English with my mother, sister, and friends, and I spoke Persian with my father and our family in Iran.

Every language, whether it is spoken by millions of people or just a few hundreds, has the potential to contribute to this understanding of our shared linguistic endowment.

Unlike my grandparents’ languages, I have few meaningful associations with English and Persian. Is it surprising that the languages I actually speak mean the least to me?

As a linguist, I can speculate about why this might be. My discipline is animated by a simple question: How is it that human children come to speak the language of their community? We know that, by the age of six or seven, children speak more or less like the adults around them, without any formal instruction. To understand how they achieve this feat, Noam Chomsky conjectured in the 1950s that all humans are born with a universal template for language, which enables them to learn any language rapidly and unconsciously. Since that time, linguists have been developing a general theory of human linguistic ability based on this hypothesis, in part through the study of individual languages. Every language, whether it is spoken by millions of people or just a few hundred, has the potential to contribute to this understanding of our shared linguistic endowment.

From this perspective, it is perhaps no surprise that my slightest associations are with the languages that I learned to speak as a child. I learned them without having to think about them. This is not, however, everyone’s experience of their language.

* * * * *

Recently, I taught a course on the languages of Mesoamerica. This cultural area is one of the most linguistically diverse places on the planet. Millions of people in what are today southern Mexico and Guatemala speak hundreds of languages, known by names like Chatino, Kaqchikel, K’iche’, Mixe, Mixtec, and Zapotec.

I teach the course, in part, to help raise the visibility of their communities in our society. Since the 1970s, these communities have responded to rising violence and the forces of globalization by making new lives in California. Today, many Mixtec, Chatino, and Zapotec people call Santa Cruz, Watsonville, and the Monterey Bay home. Many of their children are our students.

In my office hours one day, a student told me that she had been watching the lecture videos for the class with her mother. They speak the Zapotec language of their pueblo, located in the Oaxaca Valley, and they were surprised to find out that linguists were interested in their language.

As we were discussing in the class, the languages of Mesoamerica have many unique features (elaborate tone inventories in Chatino, complex gender systems in Mixtec and Zapotec), at the same time that they share many features with other languages of the world. They have, in addition, come to resemble each other in particular ways, through a long history of cultural contact. They place the verb first in the sentence, use number systems that operate on base 20, and describe spatial relations with body part terms.

My student was interested to learn these things. But she also mentioned that she didn’t think they had much to do with what she already knew about her language.

She grew up speaking Zapotec. For her, it wasn’t a verb-initial language, a tonal language, or even really a Zapotec language. It was her language. It was the language that she shared with her family and that connected her with her pueblo in Oaxaca.

* * * * *

Indigenous Oaxacans today face many challenges. Globalization and the legacy of colonialism place pressure on the autonomy of their home communities and the viability of traditional ways of making a living. In California, they frequently have difficulty accessing education and healthcare services.

But as they have done for centuries, Indigenous Oaxacans are confronting these challenges. They have founded organizations throughout California to support those in need. In Santa Cruz, the nonprofit organization Senderos has been serving the local community since 2001. In a recent conversation, I asked its Director, Fe Silva Robles, why she started Senderos with her sister Nereida:

“When we saw the great need to help our young people and children. And when we saw the discrimination, racism, and classism that there is in the community, in the schools, against Oaxacans, against Indigenous people.

You see it clearly when an Indigenous child, one of us, goes out for recess and takes a torta de frijol, and they look at them like their torta de frijol is disgusting. And then our own children start to put down the torta de frijol because they know it isn’t accepted by others.”

Senderos organizes its programming not only around encouraging pride in Indigenous culture, but also to provide basic services and educational opportunities. Particularly popular are after-school classes that teach the rich musical and dance traditions of Oaxaca to children in our community.

Fe sees language as just as important as these cultural products to their identity and sense of self-worth. She is proud to speak the Zapotec language of her town, located high in the Sierra Norte mountains of Oaxaca. In Santa Cruz, she sees few children learning their parents’ language. Fe traces this to the linguistic discrimination they face:

“They make fun of our languages…I came to Oaxaca for high school. I did elementary school in the pueblos and I came to Oaxaca for high school. They would say, “Look, the indio’s come down from the mountains! Look, they’ve come down with their huaraches.” And things like that. As I said, they make fun of our languages.

Here, in Santa Cruz, there are many children, Chatino, Zapotec, Mixtec, Trique, who don’t want to speak their language, who are ashamed to say that their parent speaks the language. And then their parents don’t speak the language, and their language is lost because of that.

To go back to your question, why don’t children learn their languages here? Because of shame, because they are scared to be discriminated against, because they don’t realize the value of this inheritance that comes from their parents and grandparents. And without wanting to, they close the door to this wonderful inheritance of language.”

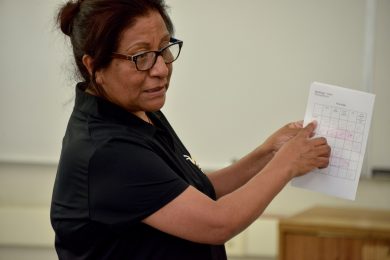

For the past four years, Fe has been teaching her language to community members in biweekly classes, supported by linguistics students and faculty at UC Santa Cruz. They have worked with her to develop an orthography for reading and writing her language, and they prepare the lessons for each class, building on their own research.

* * * * *

At the end of our conversation, I asked Fe if she remembered learning her language when growing up in Oaxaca. Her answer reminded me of what my student had said in office hours:

“It happens naturally. It happens naturally…It’s like here, a child is born and grows up in a family that speaks English, it’s natural…My first language is Zapotec, and I only learned Spanish at eight or nine years when I went to school. It’s my identity, it’s my identity. It’s my roots.

But I’m aware that it’s dying. It’s dying because of many pressures, it’s dying for the reasons that I told you before. It’s dying. So, maintaining it is a struggle, it’s a fight for those zapotecos, wherever they are, who have the opportunity and the ability to maintain it, teach it, and promote it.

But yes, it’s important. It’s very important. Language is your being. Language is you.”

We are all born with the ability to learn a language, even if we don’t remember how we did it. Some of us can go through life without ever having to think about it. For others, this endowment creates challenges to confront and to overcome. And for them, it can also be a gift, an immense treasure to be preserved and to be shared.

“Remembering Language” is part of The Humanities Institute’s 2021 Memory Series. This series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti in the Humanities community at UC Santa Cruz – each of whom highlight connections between memory and their work or meditate on memory’s relevance in our current moment. Throughout Spring quarter, be sure to look for these amazing essays in our weekly newsletter!