Wyatt Young is a second-year History PhD student at UC Santa Cruz. He is currently a year-long Public Fellow at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, where he works as a professional public humanist and local historian. His goal there is to help Santa Cruz communities develop their own historical narratives.

Wyatt Young is a second-year History PhD student at UC Santa Cruz. He is currently a year-long Public Fellow at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, where he works as a professional public humanist and local historian. His goal there is to help Santa Cruz communities develop their own historical narratives.

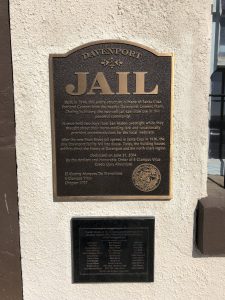

THI spoke to Wyatt about his day-to-day work; the Santa Cruz Gay Men’s Volleyball League; the “master” of the The Davenport Jail—a local octogenarian historian who inspired Wyatt to focus on that historical site; the underrepresentation of indigenous histories in local archives; and what he hopes will be the lasting impact of this fellowship.

…

You’re working with the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History (MAH) this year as a professional humanist in the exhibits and collections team. Can you tell us about this role? What does it involve, and how does your work intersect with the museum’s exhibition philosophy, and day-to-day running?

My role at the MAH working requires me to wear many hats. Some of these include: serving on local history committees for sites as the Davenport Jail, interviewing and documenting local members of the Santa Cruz community for oral history projects, and bringing to the MAH local history projects that I encounter in my daily life here in Santa Cruz.

I always have my ears open when I’m in the public because you never know when a fascinating and untold local history might present itself. For example, my work with the Santa Cruz Gay Men’s Volleyball League began through a conversation at my local dog park! While watching our dogs play together, I was informed of the history of a local marginalized group that has been active in the area for over forty years, and whose members included many prominent figures; such as local and state politicians. After hearing this, I felt compelled to help organize a public memory project that will include oral histories and a digital exhibition on their contribution to Santa Cruz history. You never know when history will present itself to you, so it’s always a good idea to be open and engage with your neighbors.

As part of your public fellowship you’re also working with local historical sites and archives around Santa Cruz County, including those connected to the Davenport jail, a tiny, two-cell jail that was built in the early 1900s. Can you tell us more about this jail and what drew you to it as a site of interest?

As part of your public fellowship you’re also working with local historical sites and archives around Santa Cruz County, including those connected to the Davenport jail, a tiny, two-cell jail that was built in the early 1900s. Can you tell us more about this jail and what drew you to it as a site of interest?

The Davenport Jail is very interesting in several ways. First, it only held two prisoners during the time it was open. Two teenage boys stole some horses and went out joyriding one night until they were caught—their parents had to come pick them up. Visitors usually get a kick out that story, because when you walk into a historic jail, it can be easy to assume there’s some dark history that made the structure significant. Instead, The Davenport Jail was primarily used as a place for locals to sleep off their intoxication before letting themselves out when they sobered up. So in a funny way Davenport can be seen as a sort of utopian or progressive form of law enforcement.

One of the things that drew me to the jail was a meeting with Alverda Orlando, a local historian who has been conducting research on Davenport and the various ethnic groups that settled in the area. Alverda is such an inspiration, she’s 88 and is still active as a public historian. In fact, she’s set to publish another book on Davenport later this year! You can find her participating in and attending lectures at UCSC or digging through the local archives doing work that a lot of academic historians might overlook. So the chance for me to work under her tutelage is perhaps one of the finest educations I could receive as a public humanist. She proves that history can be valuable and conducted at many different levels by many different people. If anyone reading this is interested in Davenport history, I can point you to the master!

One of the things that drew me to the jail was a meeting with Alverda Orlando, a local historian who has been conducting research on Davenport and the various ethnic groups that settled in the area. Alverda is such an inspiration, she’s 88 and is still active as a public historian. In fact, she’s set to publish another book on Davenport later this year! You can find her participating in and attending lectures at UCSC or digging through the local archives doing work that a lot of academic historians might overlook. So the chance for me to work under her tutelage is perhaps one of the finest educations I could receive as a public humanist. She proves that history can be valuable and conducted at many different levels by many different people. If anyone reading this is interested in Davenport history, I can point you to the master!

There must be archives connected to the jail: what can you tell us about those?

The archives connected to the jail are mostly scattered in several locations throughout the area, and Alverda has done a lot of legwork to locate and make copies of pertinent documents. As of right now, there is no centralized location for Davenport archives, but this happens all of the time in history. The articles that have been located pertain to initial migrations to the area for Swiss and Italian farmers who were brought in for the dairy and shipping industries, and then other settlers who worked in the cement factory during its operation for over a hundred years; until 2010 when it shut down. One group that is vastly underrepresented in the archives on Davenport have been the indigenous histories. I forwarded Alverda the information for members of UCSC’s American Indian Resource Center to help with the upcoming Davenport book, so hopefully accurate representation can be restored to the Davenport archives.

You plan to create public exhibits about not only the jail but other local historic sites. Can you tell about some other sites you’re interested in? And what are your goals in working with these sites and their archives?

As I mentioned above, the Gay Men’s League of Santa Cruz in conjunction with The Diversity Center Archives that the MAH recently acquired will be part of a “pod” in the local history gallery. As one of my first tasks for the MAH, I processed the Diversity Center Archives, which represent 45 years of LGBTQ+ activism and support in the Santa Cruz area. These archives tell a story of inclusion and horizontal support between these groups as they fought for human rights. My goal is to help present their history in a visual and engaging manner in an exhibit at the MAH, and also to allow access for future scholarship and research through both a physical collection and digital representations.

As I mentioned above, the Gay Men’s League of Santa Cruz in conjunction with The Diversity Center Archives that the MAH recently acquired will be part of a “pod” in the local history gallery. As one of my first tasks for the MAH, I processed the Diversity Center Archives, which represent 45 years of LGBTQ+ activism and support in the Santa Cruz area. These archives tell a story of inclusion and horizontal support between these groups as they fought for human rights. My goal is to help present their history in a visual and engaging manner in an exhibit at the MAH, and also to allow access for future scholarship and research through both a physical collection and digital representations.

You’re a second-year History PhD student, and your intellectual interests more broadly relate to museums and archiving. What is the topic of your academic research?

For my current MA Essay, I am investigating how masculinity is represented in Filipino museums in order to trace how problematic messages of Western manhood during US colonization efforts have been resisted as part of a decolonization process. It is my hopes that this will serve as a chapter of my dissertation on the presence of toxic masculinity in museum exhibits in US territories and former colonies.

What a fantastic project. How does your work in exhibits and collections with the MAH, and local history sites, relate, interconnect, or inform your academic research?

The knowledge gained from processing archival materials and going through the curatorial process directly informs my academic research. While investigating collections, it’s always important to be aware of how and why collections come into existence and how they can serve the public.

Given the amount of criticism in scholarship on the problems with archives, it’s important to also consider how they can be beneficial as well. This is not to say that archives or exhibits are infallible, but I think that understanding them fully can lead to more ways in which we might expand knowledge for all people.

Lastly, you’ve achieved a lot already, and it’s only winter quarter! What do you see as the lasting impact of this fellowship, academically or otherwise?

Lastly, you’ve achieved a lot already, and it’s only winter quarter! What do you see as the lasting impact of this fellowship, academically or otherwise?

The biggest lesson I have learned from working with the MAH, and the Special Collections here on UCSC’s campus has been to remember our public and who we are doing this research for. This work we do is valuable not only to academia but to members of our community as well, who may not have access to higher education. I hope my work helps to expand knowledge and make it accessible to the Santa Cruz public at large in ways that are engaging and help generate empathy for others.

—

THI Public Fellows Program Applications are due April 10, 2019.