Massimiliano Tomba is Chair and Professor in the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz. His most recent publications include Marx’s Temporalities (2013) and the David and Elaine Spitz Prize winner book Insurgent Universality. An Alternative Legacy of Modernity (2019).

Politics and Technologies

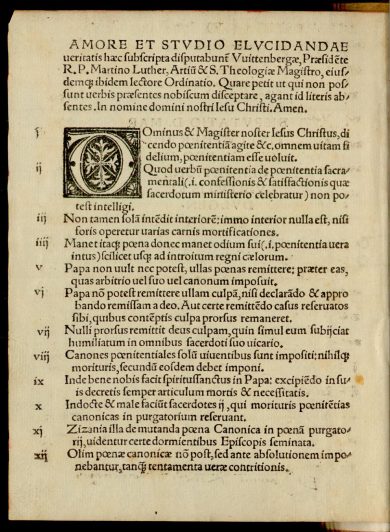

First page of the 1517 Basel printing of Martin Luther’s Theses as a pamphlet.

The advent of the printing press in the 15th century marked a significant turning point in the democratization of knowledge. Within a few decades of Gutenberg’s invention, about 1,000 printing presses appeared in Europe and 500,000 books were in circulation. This increase in text circulation was not only a quantitative shift but also a qualitative one. The power of the press, as exemplified by Martin Luther and the circulation of his Theses, was not in the press itself, but in the popularization of access to information, knowledge, and debate. This popularization challenged the existing balance of power. When Martin Luther circulated his Theses, other theses were also circulating, such as those of peasants demanding local self-government, communal ownership, and the end of slavery. The Twelve Articles of Memmingen, printed in 1525, were a testament to this. In just two months, 20 editions and 25,000 copies were printed, and the Articles circulated from Thuringia to Tyrol, from Alsace to Salzburg. In this context, letterpress printing acted as a powerful tool for disseminating texts and catalyzing new possibilities for democratization. However, these possibilities were curtailed by the actions of the princes and Luther, who preached unconditional obedience to the princes and invited them to slaughter rebellious peasants just as one slaughters a mad dog. Along with new widespread and organized rebellions, a new form of centralized and absolute power took shape.

From 1830 to 1850, major newspapers were born in France, England, and the United States. Technological innovations made it possible to print thousands of copies per hour. In 1830, the first penny press newspapers appeared on the market. Socialism spread throughout Europe. The revolutions of 1830, 1848, and the Commune of 1871 should be seen in the context of the quantitative and qualitative expansion of participation in information and the possible expansion of control over the dynamics of powers by broad strata of the population. However, this democratic mobilization also coincided with the empire of Napoleon III and new forms of plebiscitary dictatorship.

Family listening to the popular Volksempfänger, introduced in 1933 in Nazi Germany. From the German Federal Archives. Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1978-056-04A / Unknown author / CC-BY-SA 3.0

In the 1920s and 1930s, the spread of photography, radio, and cinema gave rise to a new qualitative leap in the dissemination of knowledge and, most importantly, in the participation of a broad public in these new technologies. It became possible to listen to a symphony concert or to the news from one’s radio. Cinema gave rise to a new field of experience in which, as Walter Benjamin noted, space and time were altered. A new kind of collective experience was taking shape. A large stratum of the population participated in politics, joined mass parties, had access to party newspapers, and challenged the existing order. The democracy of the masses frightened the ruling classes. It was the era of communism but also civil wars, fierce repressions, and fascist dictatorships.

Art, too, has not been immune to the democratizing effects of technology. In the 20th century, the distance between the work and the audience began to shrink, and the aura of art was dissolving. This shift was not a triumph of spectator passivity but a transformation of the audience into quasi-experts. At the beginning of the last century, people gathered to discuss what they read in the newspaper. Any person could claim to be photographed. Today, technology allows everyone to film and make their own short films public. Any reader can claim to be an author and publish their texts on a virtual platform. This has opened up new avenues for participation in the arts, politics, and other spheres.

Power compensates for the absence of unity.

While the Internet has undoubtedly expanded access to and production of information, it has also brought about new challenges. The rise of social media has allowed anyone to become a journalist, commentator, or expert. It has also facilitated the gathering of followers around individuals, leading to the fragmentation of reality into independent bubbles. This fragmentation of the real into a multiplicity of points of view and pieces of reality subsisting as independent bubbles gives rise to new authoritarian phenomena. Power compensates for the absence of unity.

At the same time, new technologies change the perspective from which large strata of the population look at politics and politicians. They enable people to increase their knowledge, participation, and, at least potentially, control of the business of politics. But as the distance between the politicians and the masses decreases, politics becomes a spectacle. Entertainment. Politicians increasingly act as pitchmen selling a cheap commodity: themselves.

The theater of politics, which Hobbes had emptied by moving all individuals into the body politic of the sovereign, now has stalls full of spectators who are not passive. It is no longer the educated public sphere of the 18th Century idealized by Kant. It is more like the republican festival described by Rousseau in his Letter to d’Alembert on the theater: people gather together, and “spectators become an entertainment to themselves.” They become “actors themselves.” The theater is turbulent. The audience takes the stage. People want to be not only actors, but also authors. Once again, the excess of democracy in action by the masses disturbs the stable democratic order.

Modern political history is characterized by the tension between an institutional form designed to contain democracy and the democratic practice that exceeds that form.

The absolute monarchies of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Bonapartism of the nineteenth century, the fascisms of the twentieth century, and the more recent forms of authoritarianism are not the result of new technologies used for control, propaganda, and manipulation. They are reactions to democratic excess. Modern political history is characterized by the tension between an institutional form designed to contain democracy and the democratic practice that exceeds that form. Containing and curbing the “excess of democracy” in the thirteen state governments was the goal of Alexander Hamilton, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. It was also the goal of Robespierre in France during the Revolution. The democratic excess had to be anesthetized and encapsulated in the heart of the state, i.e., in the ever-present possibility of evoking exceptional powers to restore the stability threatened by the democratic excess. New technologies do not produce this. Rather, new technologies give the imprisoned excess new avenues of expression that disrupt a given balance of powers and its precarious stability.

The political institutions of modernity, the still much-celebrated model of representative democracy, can only withstand a certain degree of democratization. When demos-cracy, in the action of the demos, exceeds established representative structures and power relations, instability ensues. True democracy is this instability. Authoritarianism and dictatorships emerge as reactive measures to create new stability and contain the excess. The history of the modern state, its philosophy, is characterized by this oscillation between demos-cracy and its restraint. The alternative is to learn, experiment, and practice new ways of managing an unstable democracy in which conflict is not the evil to be eliminated but an essential dimension of political life. The alternative is to learn how to manage and control the potential for democratization unleashed by new technologies. The alternative is to learn how the demos can control these technologies rather than leaving them in the hands of a few individuals.

Banner Image: Social media apps on an iPhone screen, by Nathan Dumlao.

The Humanities Institute’s 2024 Technology Series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti engaged in humanities scholarship at UC Santa Cruz. The statements, views, and data contained in these pieces belong to the individual contributors and draw on their academic expertise and insight. This series showcases the ways in which scholars from diverse disciplinary perspectives contend with the issues connected with our annual theme. Sign up for our newsletter to receive the latest piece in the series every week!