Travel Series: Elaine Sullivan

Elaine Sullivan is Associate Professor of History and is affiliated with the Anthropology Department, Classical Studies program, and the Archaeological Research Center. An Egyptologist and a Digital Humanist, Dr. Sullivan’s work focuses on applying new technologies to ancient cultural materials. She acts as the project coordinator of the Digital Karnak Project, a multi-phased 3D virtual reality model of the famous ancient Egyptian temple complex of Karnak. She is project director of 3D Saqqara, which harnesses Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technologies and 3D modeling to explore the ritual and natural landscape of the famous cemetery of Saqqara through both space and time.

Her field experience in Egypt includes five seasons of excavation with Johns Hopkins University at the temple of the goddess Mut (Luxor), as well as four seasons in the field with a UCLA project in the Egyptian Fayum, at the Greco-Roman town of Karanis.

Because of a broad interest in the history and material culture of the larger ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean worlds, she has also excavated at sites in Syria, Italy and Israel. Dr. Sullivan received her M.A. and Ph.D. in Egyptian Art and Archaeology from Johns Hopkins University. Her B.A. (Magna Cum Laude) in History is from Duke University.

(Virtual) Travel Back in Time?

If you asked any archaeologist where in the world would they travel if they could go absolutely anywhere— I bet 95% of them would tell you that the question is not where they would want to go, but when. As an Egyptologist and scholar fascinated with all aspects of the ancient world, I would love to be able to journey back in time and see, feel, and experience the place that is the focus of my work today, ancient Egypt. Historians are well-aware that even with all the materials of the past (such as statues, stelae, and texts) carefully preserved in museums, and the monuments, towns, and tombs continually uncovered through excavation, we still only have a fragmentary picture of what it was like to live back then: it is as if we are squinting through a broken window, wearing sunglasses, while standing on our heads.

I would love to be able to journey back in time and see, feel, and experience the place that is the focus of my work today, ancient Egypt.

Egypt’s Pharaonic Period ended in 332 BCE, and 1500 plus years of cultural change are too much for us to ever overcome, even with the most active imaginations. Archaeologists can reveal the foundations of an ancient family’s house, but we cannot know what people thought each day when they made offerings to their ancestors before a small shrine. Art Historians study the intricately painted tombs of the royals and elites, but we don’t fully know what it sounded, smelled, or felt like to walk in an elaborate funeral procession, following the mummy to its final resting place in the western hills. Historians can read the royal propaganda etched in stone on monumental temple walls, but we wonder if regular Egyptians really cared who was king, or if they walked by the high mud-brick walls rimming the sacred spaces and thought the ancient equivalent of “whatever.”

Ancient Egypt’s language, culture, and religion all disappeared in the 1st millennium BCE, supplanted by new peoples, new ideas, and new gods, but the very landscape of Egypt has also altered in radical ways that make imagining the past world so difficult. The Nile no longer rises each year, creating the cyclical flood that made the early state so successful,[1] modern buildings have crept out over and subsumed ancient places, and once-impressive monuments have disappeared due to human intervention and the centuries of sand, wind, and rain.

Students in my UCSC courses frequently ask me at what moment in Egyptian history I would most like to be a fly on the wall. Well, I’d be tempted to pop back to the reign of Pharoah Hatshepsut (1473-1458 BCE), one of the Egyptian state’s only female kings across its 2700 years. Acting as Queen regent for her deceased husband’s baby son (and expected successor to his father’s throne),[2] she declared herself Pharoah and became the “living Horus,” the (male) son of the Egyptian god Osiris on earth, a decidedly tough mythological and political role for a woman to fill. Egypt was a patriarchal state, with a sophisticated artistic tradition which depicted human bodies in binary genders through the use of conventions such as skin color (women typically with yellow, men with red), clothing types, and body proportions.[3] Hatshepsut’s preserved statuary (which you can view if you visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) reflects the challenges for a person trying to adapt to a role with almost 1500 years of male kings as precedent: in one image she presents herself in the typical closely fitted feminine sheath dress, covering her from neck to ankle (left); in another she is depicted in the traditional garb of a male king, wearing the typical short pleated kilt with a bare chest and lower legs, but her body still maintains a slim female figure and her chest ambiguously hints at the presence of breasts (center); other statues represent her as a fully male king, with the buff arms and brawny shoulders typical of the heroic male royal in Old Kingdom and New Kingdom Egyptian art (right).

Center: Limestone seated statue of Hatshepsut in the clothing of a male pharaoh, OA image from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Right: Granite standing statue of pharaoh Hatshepsut with male-gendered clothing and body form, OA image from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

How did this female king negotiate gendered power in real life? Did she need to run the state with as much flexibility as exhibited in her art, shifting between gendered roles depending on her audience or duty? Did the members of the court and state administration object (perhaps under their breaths) to this break with traditional father-to-son succession, or was this seen merely as a novel strategy with the next king still a child? Despite being (what looks to us) like a pretty successful king, Hatshepsut’s royal image and name were intentionally erased from Egyptian history after her death.[4] Was that punishment for disturbing the gendered status quo? Egyptian sources are frustratingly silent on all these points, and I’d certainly like to know.

Using constantly improving 3D technologies, I’ve collaborated on a series of projects that virtually reimagine ancient Egyptian sites at their moments of use in the past.

Of course, I’d be equally interested in experiencing the mundane of everyday life. A common funerary formula inscribed on tombs and offering tables in Egypt requested “a thousand of bread, a thousand of beer… for the ka (spirit) of the blessed one,” and the Egyptians believed that one’s eternal form needed sustenance just as one did when alive (the Egyptians were extremely practical people and planned meticulously for death, stocking their tombs with food, drink and linen clothing, and made sure to also include papyrus scrolls with the key ‘passwords’ to travel through the gates to the afterlife. I think of them as the world’s first ‘preppers’). Bread and beer were the staples of the Egyptian diet, and my time-traveling self would be thrilled to sit down to taste them both. Experimental archaeologists have attempted to bake ancient-style bread,[5] and passionate beer makers have tried to brew something like an ancient ale,[6] but there are many ways a recipe can go wrong (especially when you don’t know all the ingredients or the exact steps of preparation), and there are few joys of travel more well understood than eating local food where it is made, by the people who make it everyday.

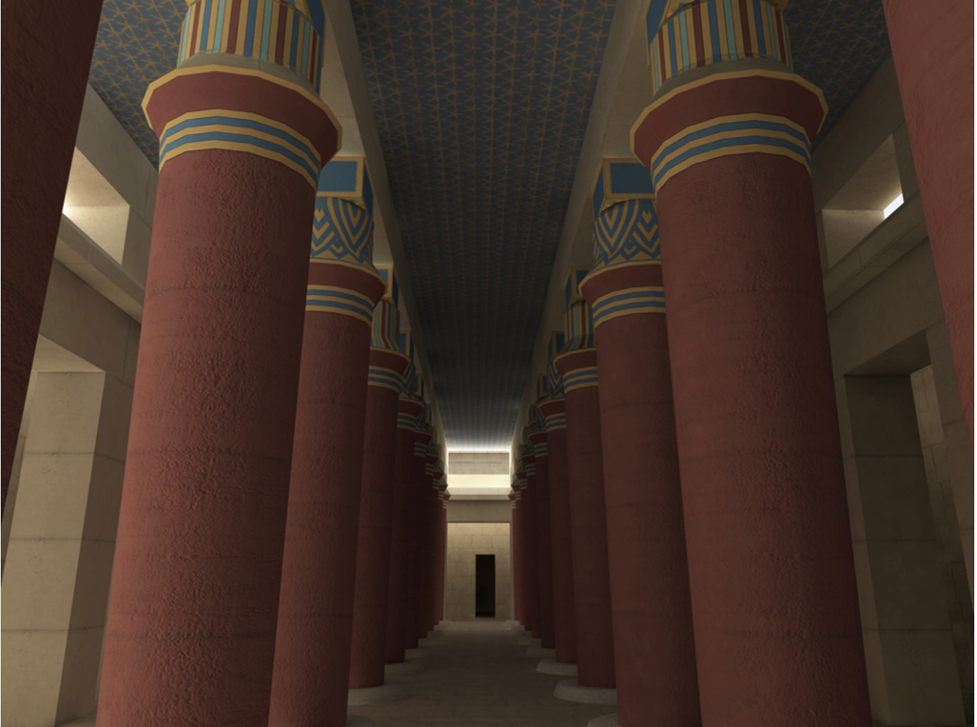

Time-travel is of course a popular subject of Literature and Film, yet Historians usually keep out of it. But I confess that in the past years, I’ve been dipping my toe in, just a bit. Using constantly improving 3D technologies, I’ve collaborated on a series of projects that virtually reimagine ancient Egyptian sites at their moments of use in the past. We digitally rebuild temples, spread the remaining flecks of paint fully across entire walls or columns, repair broken pavements, and reassemble collapsed roofs, all with a few clicks of the mouse.[7] In these augmented worlds, we are better able to visualize the rich colors and textures that originally animated such ritual spaces, much of which has faded in modern times.

In one of my 3D projects, I visualized the major funerary monuments constructed at the ancient cemetery of Saqqara as the sacred space grew and changed over time, and I used my 3D model to virtually ‘stand’ inside the cemetery, wander around a simulated landscape, and speculate on why the ancient Egyptians chose specific locations for their tombs.[8] Not quite time-travel, but 3D does give me the chance to consider things in a virtual world that no longer exist (or do not exist in their original form) in real life today at the site.

Since 2018, I’ve been working with a colleague at UC Berkeley, Dr. Rita Lucarelli, and a team of UC students and staff on a Virtual Reality headset application that will allow members of the public to virtually visit the Saqqara necropolis and descend into the tomb of an ancient Egyptian elite named Psamtek who lived during Egypt’s Late Period (~550 BCE). The Phoebe A. Hearst Museum has the lid of Psamtek’s inner stone sarcophagus, which a UC Berkeley team documented in 3D,[9] and we’ve virtually replaced it back into Psamtek’s reconstructed tomb in our VR application.[10]

Standing (virtually) in Psamtek’s tomb at the bottom of a shaft cut more than 25m below the desert surface is an illuminating experience; one can barely move. His huge outer sarcophagus almost completely fills the space. The burial chamber was not meant to be visited, but closed and inaccessible —it needed only to be large enough to hold Psamtek’s funerary equipment, and for a few men to maneuver within to place Psamtek’s body inside at his death. The tomb today is not open to visitors at Saqqara, so despite the many times I’ve been to the site, I’ve never been inside it in real life, only virtually.

Putting on the VR headset, I know I’m not time-traveling, not really, but it might be the closest thing I will ever experience to it, unless Google invents a functioning Stargate.[11] I feel that I am inside the tomb; I bend down and peer under the outer sarcophagus lid to glimpse the inner lid, etched with elaborate spells to protect Psamtek’s eternal spirit, I carefully inch around to peer into the shaft behind me, I worry about hitting my head (foolishly, since the ceiling is virtual). Psamtek’s basalt inner sarcophagus lid is back in place, for the first time since 1903,[12] when it still sat ready and waiting to cover the body of its owner, who (for reasons unknown to us) never was interred here.

Time-travel may not be on our horizon any time soon, but VR offers me rich opportunities to contemplate what we know and do not know about the past.

3D and VR technologies have rapidly grown ever more impressive, and immersive experiences can now include audio, smells, and even reproduce a sense of touch in the virtual world. Our project on the Saqqara tomb of Psamtek could add the sound of blowing sand as one walked along the desert surface, allow the virtual visitor to pick up and inspect the canopic jars found in one of the tomb’s chambers, or saturate the room with the scent of juniper and cedar oil, fragrant substances used in the mummification process during this era at Saqqara.[13] I hope to add all of these elements to our VR experience. Despite such capabilities, I know that VR can never truly replicate the past, it is merely a representation of what we, as modern people, think we know about the past. But it is the process of trying to imagine (and digitally recreate) this illusive past that provokes new kinds of questions for me as a Historian, questions about sensory experience, movement through space, and about how ancient people lived with and reshaped the built environment of their ancestors. Time-travel may not be on our horizon any time soon, but VR offers me rich opportunities to contemplate what we know and do not know about the past.

“(Virtual) Travel Back in Time?” is part of The Humanities Institute’s 2023 Travel Series. This series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti in the Humanities community at UC Santa Cruz – each of whom highlight connections between travel and their work or consider the role of travel in their fields. Throughout Spring quarter, be sure to look for these amazing essays in our weekly newsletter!

References

[1]. The Aswan High dam, completed in 1970, moderates water output to create a perennial growing season in Egypt, and the Nile therefore no longer rises seasonally (following Ethiopia’s rainy season, which caused the Blue Nile, the main tributary of the Nile, to swell) north of the city of Aswan. The Aswan Low dam, completed in 1902, was a precursor to the High dam, and built under the direction of British irrigation engineers also to promote year-round agriculture. My UCSC History department colleague Dr. Jennifer Derr recently published an award-winning book examining the ramifications of building that early 20th century dam, called The Lived Nile: Environment, Disease, and Material Colonial Economy in Egypt: https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=29529.

[2]. Hatshepsut was the “great royal wife” of king Thutmose II, but they had a daughter, Neferure, and not a son. The Egyptian king in the New Kingdom married multiple wives, likely in a strategic attempt to guarantee that a son would live to act as his successor (something that is definitely not guaranteed when a king has only one wife, and causes endless hand-wringing. Just ask Henry VIII.) Thutmose II had a son, the future Thutmose III, by a secondary wife, and Hatshepsut was acting as regent for this child when she took the throne. She depicts him with her (in a secondary position) on some of her artwork.

[3]. The foundational study of gendered art in Egypt is Gay Robins, Women in Ancient Egypt (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993).

[4]. For example, the Dynasty 18 king Hatshepsut is excluded from the “king list” of Dynasty 19 Pharoah Sety I at his memorial temple at Abydos. The succession is listed as Thutmose II (Aakheperenra), followed directly by Thutmose III (Menkheperra), as if Hatshepsut’s 15-year-reign never happened. Wikipedia has quality images of this scene and the name of the kings: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abydos_King_List. The king list of Dynasty 19 king Ramesses II (son of Sety I) also omits Hatshepsut: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA117. This omission was obviously not an accident.

[5]. One experiment even scraped ancient yeast from Old Kingdom vessels, and then used the yeast to bake bread with barley and other ingredients that would have been available to the Egyptians at the time: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/bread-was-made-using-4500-year-old-egyptian-yeast-180972842/

[6]. Dogfish brewery bottled one called ta henket (translated from the Egyptian word for “beer”) in 2010, which I searched for but, disappointingly, never could find to taste: https://www.dogfish.com/brewery/beer/ta-henket)

[7]. The Digital Karnak project, which virtually re-constructed the temple to the god Amun-Re of Karnak in the reign of multiple Egyptian and Greco-Roman period kings, was created in 2007-08 at UCLA, and is now hosted through UCSC: https://digitalkarnak.ucsc.edu.

[8]. The open-source monograph can be read online: Elaine Sullivan, Constructing the Sacred: Visibility and Ritual Landscape at the Egyptian Necropolis of Saqqara (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2020), http://constructingthesacred.org.

[9]. https://3dcoffins.berkeley.edu/coffins/pahma-5-522.

[10]. The initial exploratory work for this project was funded by a UC CITRIS seed-funding grant. The project is under development and has now expanded out to include a second tomb at Saqqara and new international collaborations. We hope to eventually release the VR headset app freely to the public.

[11]. Just kidding. Stargate, the 1994 Science Fiction hit movie, sent Kurt Russell, James Spader, and their team through a “stargate” to a distant fictional planet (called ‘Abydos,’ a planet ‘like’ but not ancient Egypt). The movie had a convoluted plot about aliens, Egyptian gods, and other nonsense that I can’t fully remember, but I blame it for many of the absurd ideas that still proliferate in pseudo-scientific media about pyramids being constructed by aliens as ‘landing pads’ for their space craft.

[12]. The sarcophagus lid was probably purchased by William Randolph Hearst himself on a trip to Egypt and shipped to Berkeley in 1903. At that time, Egyptian antiquities laws allowed objects to legally leave the country.

[13]. Maxime Rageot et al., “Biomolecular Analyses Enable New Insights into Ancient Egyptian Embalming,” Nature 614, no. 7947 (February 2023): 287–93, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05663-4.