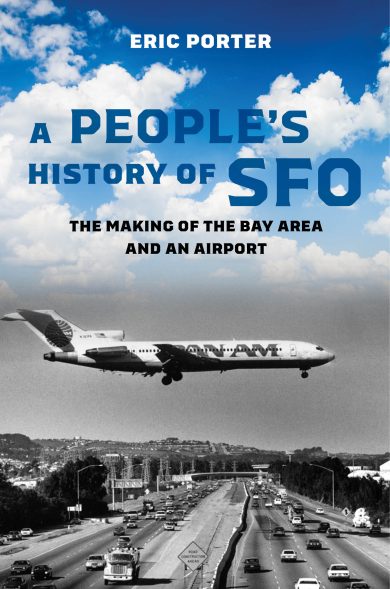

Travel Series: Eric Porter

Eric Porter is Professor of History, History of Consciousness, and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at UC Santa Cruz. His work spans Black cultural and intellectual history; US cultural history and cultural studies; critical race and ethnic studies; jazz and improvisation studies; Black radicalism; and urban studies. In 2021, Porter co-edited the volume Sound Changes: Improvisation and Transcultural Difference, which offers an introduction to a range of musical expressions across the globe in which improvisation plays a key role. His most recent book, A People’s History of SFO: The Making of the Bay Area and an Airport, views SFO as a “microcosm of the forces that have been and are at work in the Bay Area—from its colonial history and early role in trade, mining, and agriculture to the economic growth, social sanctuary, and environmental transformations of the twentieth century.” His contribution to our 2023 Travel Series draws on the work in this book to exemplify how airports can be understood as points of contact for people, infrastructures, and ideologies that reveal the workings of the larger culture.

How to Read an Airport

Travel, whether chosen or imposed, is an index of human conditions and aspirations, as well as our relations to place and to one another.

Travel, whether chosen or imposed, is an index of human conditions and aspirations, as well as our relations to place and to one another. Those entangled relations, with their asymmetrical interfaces, are transformed and revealed at different stages of travel: from the realization that it is possible, necessary, or will be forced upon us; through the process of movement itself; and, again, at arrival and return. Such relations are also, of course, shaped by mechanisms of conveyance—whether those are worn-out shoes, hopped-on freight cars, RVs, or luxury jets—as well as by the infrastructures supporting travel. These things are revelatory as well.

Take airports, those complexly networked infrastructures whose operations over the years have, in regionally specific yet far reaching ways, drawn together and been made and shaped by the interactions among various groups of humans (workers, tourists, migrants, and others); municipal, state, and federal laws and regulations; economic flows of different scales; built urban, suburban, and exurban environments; and natural phenomena. As such, airports and their operations illuminate how people from multiple backgrounds, with different access to power and resources, have abided, resisted, and otherwise negotiated the powerful forces that have shaped their lives.

Airports and their operations illuminate how people from multiple backgrounds, with different access to power and resources, have abided, resisted, and otherwise negotiated the powerful forces that have shaped their lives.

Indeed, complex race, gender, class, and citizenship dynamics unfold inside metropolitan airport terminals that have served as transportation hubs, ports of entry, dining destinations, and, more recently, high-end shopping malls and museums. Once the province of elite travelers, airports used to sort people largely by who flew and who did not. Now they do so by the paid work people do there, the scrutiny paid to them at the security gates, the passports they hold and the questions asked of them at customs, where they shop and eat, their access or not to airline lounges, and whom they queue up before and after as they board their flights.

Travelers are surveilled and profiled with attention to national, racial, religious, ethnic, and gendered difference. Some are screened for their assumed, terroristic threat to the state and public safety. Others are sorted into processing categories—citizens, permanent residents, immigrants, work visa holders, tourists (visa holding and not), and refugees—while their right to pass through these portals of mobility or, in the case of international airports, their right to enter or leave a country or bloc of countries is determined. Such processes have been enhanced in recent decades amid assumed terrorist, immigrant, and refugee threats, but they have been developing at airports for as long as they have been ports of entry.

The goal of such management of traveling bodies—often executed by government agents with some discretionary power to enforce immigration and transit rules as they see fit— is to cultivate certain national or regional futures and to prevent others from occurring. Travelers, in turn, perform their deservingness—and their own participation in such futures—by presenting documents, answering questions, permitting themselves and their belongings to be scanned and searched, and queueing up with only minimal complaint. Accepting the protocols of identification bound up in the systems of governance that come together at airports or having such protocols imposed on an individual or group has tended to reproduce power. Refusing those protocols has been where the politics of belonging intensify, where aspects of power and its exclusions have been made visible, challenged to various extents, but generally, in the end, reconstituted.

Travelers, of course, sort themselves in relation to one another and to those who work at airports: customs agents, local police, gate agents, security gate personnel, janitorial staff, and fast-food workers. Take those common scenes of service work at airports, redolent with regional and global social dynamics, that draw in travelers temporarily to enact their relative privileges and precarities. The white people working the fast-food counters at Sea-Tac in the early 1990s showed the declining fortunes of that working class in the area as some of the young professionals they served in-transit drove up rents and home sale prices. A decade later, a white woman purposefully tossing trash at the feet of a veiled, Somali custodial worker at Phoenix Sky Harbor made clear rising Islamophobia, the changing face of anti-Blackness, and the challenges facing East African immigrants in the region after 9/11. Two decades after that, multi-hued members of a jet-setting elite, expressing their frustration with security screening protocols and their disdain of Filipinx security workers paid to enforce them at SFO’s International Terminal, spoke of shifting, transnational dynamics of racial and class animus as well as attendant, global patterns of servitude. That these security workers were significantly better paid than they were a couple of decades earlier reflected a local history of SEIU organizing and an array of living wage campaigns and municipal ordinances in and around San Francisco. But the fact that their ranks no longer included non-citizens manifested the inability of local activists and politicians to change the new US citizenship requirement for airport security workers in the Aviation Transportation and Security Act (ATSA), signed into law in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

Exclusions and complicities, resonant with past events and emergent phenomena, proliferate in and around airports.

In other words, exclusions and complicities, resonant with past events and emergent phenomena, proliferate in and around airports. They are the scene of the whirling dance of contingent encounters where human actions and networks are brought together in medias res in ways that simultaneously define and transcend these regionally-specific yet far reaching infrastructures. Airport concourses (and the terminals where they are situated) are, after all, sites where concourses (i.e., gatherings, per another definition of the term) of multiple human actors engage in concourse (i.e., cooperative or combined actions, per yet another definition) with one another and with nonhuman things. They are also where we observe one another engaged in such encounters, under and exceeding the surveilling eye of the state. Airports are thus key sites where asymmetrical relations, both locally specific and globally-connected, are reproduced through travel and revealed to us.

Adapted from A People’s History of SFO: The Making of the Bay Area and an Airport

Banner Image: An aerial photo of San Francisco International Airport (SFO) taken in 2015 from a light aircraft. Image from Wikimedia Commons, user Russss.

“How to Read an Airport” is part of The Humanities Institute’s 2023 Travel Series. This series features contributions from a range of faculty and emeriti in the Humanities community at UC Santa Cruz – each of whom highlight connections between travel and their work or consider the role of travel in their fields. Throughout Spring quarter, be sure to look for these amazing essays in our weekly newsletter!