Week 1: Conversations with Twain—James Speaks Back

Welcome to the 2025 Deep Read!

This is the first of four emails exploring James by Percival Everett. Our email series aims to enhance your reading experience of the novel by sharing insights, observations, and questions raised by faculty here at UC Santa Cruz and by your community of fellow Deep Readers in Santa Cruz and around the world. Today, we’ll meet the faculty who will help us read the book and navigate its literary, historical, and cultural terrain. We’ll also suggest themes to explore as you begin reading James and offer insights into various ways of reading deeply. This week, you’ll want to read through Chapter 13 of Part 1. Let’s get started!

Meet the Faculty

Vilashini Cooppan, Professor of Literature, is a scholar of comparative and world literature, with an emphasis on postcolonial theory, genre theory, critical theory, and memory studies. She will bring her expertise to the Quarry event on May 4 where she will be in conversation with Percival Everett.

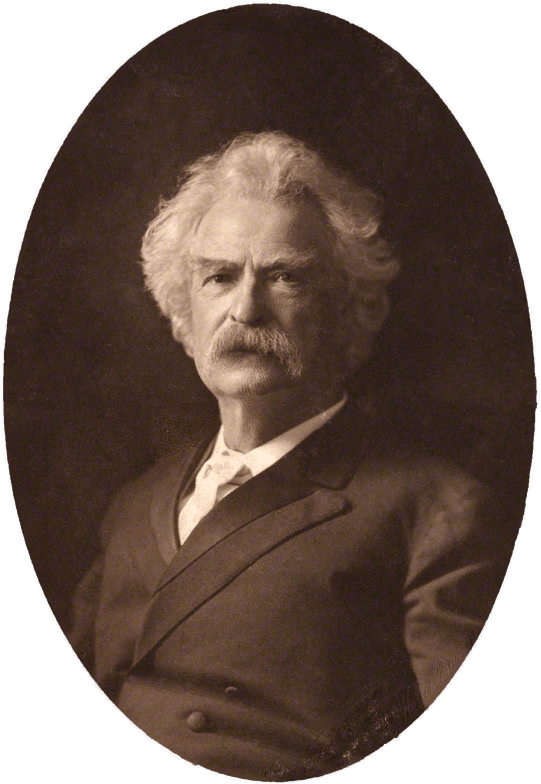

Susan Gillman, Professor of Literature, is a Mark Twain scholar whose work spans 19th-century American literature, race theory, and genre studies. She will situate James in the tradition of 19th-century American literature and satire and help us understand the novel’s relationship to Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Laura Martin, Lecturer and Program Manager for the Deep Read, is a literary scholar who teaches the Deep Read course and moderates the faculty salon each year. She’s been a key part of the Deep Read since its launch and her literary training and interests keep the humanities central to the email series and every book we read together.

akua naru, Assistant Professor of Music, is a hip-hop artist, lyricist, and historian whose work centers on Black expressive culture and the Black radical tradition. She brings a poetic, critical, and performative lens to James, helping us to understand the role of music and performance in the novel, along with the novel’s politics of race.

Greg O’Malley, Professor of History, is a scholar of the Atlantic slave trade whose work is focused on broadening and deepening our understanding of Atlantic slavery and the slave trade. He will help us grasp important historical contexts of James, especially how the novel imagines freedom, geography, resistance, and the history of slavery.

Micah Perks, Professor of Literature and Creative Writing, is a writer of fiction and memoir whose work explores coming-of-age, utopian communities and the American imagination. She will bring her expertise as a writer to the Deep Read Craft Salon on April 22 where she will discuss the writing craft and techniques of James.

Karen Tei Yamashita, Professor Emerita of Literature and Creative Writing, is known for her genre-defying fiction and theatrical, satirical style that interrogates race, history, and power. She will discuss the writing craft and techniques of James with Prof. Perks at the Deep Read Craft Salon on April 22.

A Conversation Across Time: Percival Everett and Mark Twain

There are many ways to think about the relationship between Percival Everett’s James and Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and each possibility carries with it certain assumptions. We could understand James as a “rewriting” or “revision” of Huckleberry Finn, which suggests that Everett’s novel is taking a critical approach to its predecessor, “correcting” something that was “wrong” or amiss in Twain’s novel. We could also take James as a “reimagining” of Huckleberry Finn (a word many reviewers of the novel have used); this approach implies a cozier but not wholly uncritical relationship between the two authors, one in which Twain’s novel works as generative ground for Everett to pick up on, reanimate, and rework. Alternatively, we could imagine James as an “adaptation” or “translation” of Huckleberry Finn. This approach situates Twain’s novel as a clear source text but presents James as a transformation of the original, implying less fidelity to Twain and a more neutral relationship between the two authors and books.

Percival Everett, when asked about his relationship to Twain and Huckleberry Finn, though, takes a different tack, often saying that he is “in conversation” with Twain. In his Booker Prize interview, Everett names Huckleberry Finn as a “source” for his novel and says this: “I hope that I have written the novel that Twain did not and also could not have written. I do not view the work as a corrective, but rather I see myself in conversation with Twain.” Instead of a correction, Everett is asking us to see James as part of a dialogue, one side of a back-and-forth exchange he is having with Twain and Huckleberry Finn. We’ll want to keep this in mind as we read James together. What does it mean for a novel to be in dialogue with another novel, especially such a charged canonical text like Huckleberry Finn? How is Everett in conversation with Twain exactly and to what effect?

Literature professor and Twain scholar, Susan Gillman, gives us a helpful way into answering these initial questions and understanding the Everett/Twain conversation that is James: “Everett is taking Huck Finn and deepening and extending it. He’s not correcting it … he’s using both the limits and the possibilities of what you could say — and how you could say it — about race and slavery in the 1880s, and bringing that to now.”

As you begin to read the novel this week, you might consider how Everett is deepening and extending what Twain could say and understand about race and slavery in the late 19th-century. We’ll explore some ways he is doing this below and in the coming weeks. If you missed Professor Gillman’s presentation on Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at the Twain Deep Read salon in February and would like to brush up on Twain and his novel, you can view her remarks here.

Conversational Touchstones: Themes, Contexts, and Shifts in James

While some themes and contexts from Huckleberry Finn remain in James, many change, or are expanded and extended, as Prof. Gillman explains. Here are some to take note of as you read the first thirteen chapters of Part 1 this week:

Historical Context

Both Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and James are set before the Civil War, but their historical contexts are different. Mark Twain published Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in the mid-1880s, but he set the novel several decades earlier, in the 1830s-40s. Percival Everett’s James, by contrast, takes place closer to the 1860s, on the eve of the Civil War. This shift in time period is more than cosmetic. It reshapes the stakes of the narrative in important ways, which we’ll think through in the coming weeks.

Narrative Perspective and Naming

Perhaps the most obvious change that Everett makes is to shift the narrative perspective from Huck to Jim, changing Jim’s diminutive name into his full name, James, in the process. Here, James and his concerns are foregrounded, and we learn about his experience of enslavement and quest for freedom directly and without mediation from Huck. New possibilities and critiques emerge from this shift, which we will explore together.

Literary Genre

Everett is also playing with genre. While James shares elements with 19th-century slave narratives, the novel also has generic ties to Huckleberry Finn and the tradition of American frontier humor. We’ll think more about how Everett merges the slave narrative form with frontier humor to produce a unique novelistic form.

Language

One of the novel’s most striking features is how it depicts the language of the enslaved characters. James shifts registers constantly—between language the white characters expect to hear from slaves and what he and his fellow slaves think, feel, and say when alone or among each other. We’ll think carefully together about what the language of the novel is doing and what it suggests about the role of language in the quest for freedom, survival, and resistance.

Slavery, Race, and Performance

The depiction of language in the novel is one part of a broader representation of slavery as a multi-faceted performance that is “put on” for the master and other white characters. Everett weaves language, religion, education, and more together to present slavery as a complicated mode of representation and a satirical performance connected to the tradition of blackface minstrelsy, which we’ll delve into when it appears later in the novel.

Music and Rhythm

James begins with excerpts from the notebooks of Daniel Decatur Emmett, a character and historical figure who will appear in subsequent chapters of the novel. An American composer (he wrote “Dixie”), Emmett is also the founder of the Virginia Minstrels, one of the first blackface minstrel troupes in the U.S. We’ll stay attuned to how music is evoked in the book and how the novel invites us to pay attention to its sonic elements – its rhythm, tone, repetition, and breaks.

Reading, Storytelling, and Subversion

One invention of Everett’s James is to depict James as a literate and educated slave. He reads, writes, and is well-versed in a wide range of literary, historical, and philosophical debates. The novel is also full of stories within stories—riddles, fables, philosophical arguments, and jokes. In interviews, Everett often refers to storytelling and reading in particular as a form of “subversion,” calling reading, in one interview, “one of the most subversive things we can do.” We’ll want to notice when reading, writing, and literacy appear in the novel and consider what Everett might be saying through these themes.

Joining the Conversation: How Do We Read Deeply?

In a moment when our attention is constantly fractured—by news alerts, emails, feeds, and tabs—the act of sitting with a novel has become increasingly rare and increasingly radical, as Everett suggests. Deep reading asks us to slow down. To listen closely. To look again. It’s not just about what a book says, but how we show up to meet it, how we listen to it and engage with it. Part of what the Deep Read offers is an invitation to think about your own reading practices as we read together.

We asked some of our Deep Read scholars to share what Deep Reading looks like to them. We hope it will get you thinking about what it looks like for you as you begin James:

For akua naru, reading is an active and reflective process:

“With reading, I need to have time, because a lot of reading and writing for me is thinking. Deep reading, for me, is approaching the text with a series of questions based on whatever my purpose is with regards to why I’m engaging with this text. And then having the space to write and record things as I’m actually engaging with that text.”

Susan Gillman approaches deep reading as an interplay between close reading and historical context:

“I think deep reading combines close and distant reading. Deep reading is a way to historicize books. It always thinks of a book in context … deep reading is aware of the historical context for a text and then, further, deep reading goes inside the text and looks at the language with this context in mind.”

For Greg O’Malley, deep reading is an empathetic process of slowing down to connect with the author and their perspective:

“I like to read texts slowly and thoroughly … I think the act of reading fosters empathy … it takes you to the perspective of the author of that work. And I think there’s something really deeply valuable about that …You have to really sit with it.”

As our Deep Read scholars illustrate, there are many ways to read deeply. Deep reading can mean close textual analysis, historical contextualization, asking thoughtful questions, or sitting with a book and letting it speak to you and unfold into a new perspective.

Community Conversations

As you begin James, we hope you’ll reflect on your own reading, too. What does deep reading look like for you? In particular, how are you reading James? What questions and issues raised by the novel seem most interesting and important to you so far? Are you noticing some of the themes and contexts that we pointed to above, and what are you noticing about them? Are you noticing ones not mentioned here?

What do you think about Everett’s claim vis-a-vis Twain, that he is “in conversation” with Twain and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in James? What do you think they’re conversing about? What kind of conversation is this if Twain can no longer respond? Finally, how do we, as readers, fit into this model? Are we meant to be part of the conversation, too? And if so, how?

Please share your thoughts and insights in the comments section below. As Prof. naru reminds us, “Reading is a conversation. And if it can happen in community, that’s where the magic happens.”

We’re so glad to be reading with you.