Grad Profile: Kendall Grady

Kendall Grady is a PhD candidate in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. Their creative/critical dissertation explores the connection between media ecology and critical love studies alongside a manuscript of love poems in couplets. In a recent interview, we learned more about Grady’s ongoing writing and public humanities work. Grady received a 2022 THI Summer Public Fellowship to work with Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music, an annual festival “dedicated to the creation and performance of profound, relevant, and innovative music.” They also received a 2022 THI Summer Research Fellowship to support their research trip to visit two love museums in Croatia. We discussed Grady’s critical and creative approaches to love, and the unexpected, delightful couplings that can happen across curatorial spaces and creative mediums.

Hi Kendall! Thanks for chatting with us about your public fellowship work and your ongoing research and writing projects. To begin, could you give us a general synopsis of your dissertation project and, more specifically, the research you focused on this summer?

If I’m being candidly honest, my research is a response to having my heart broken. Like, truly mangled. More than once. And despite how exceptional romantic love can make us feel, and how pointedly wrenching its loss can seem, these experiences are not novel. In fact, in my grief I felt cliche—the refrain of every radio ballad, the trailer for every Hallmark Channel original movie, the tired rite of passage through a (pop) cultural vocabulary that frames love as an interior landscape, places it on a pedestal, and dares us to stay there. However, the poet Eileen Myles writes that “[T]he trick to being in any relationship is that you have to keep deciding not to destroy it… So when it feels like your boat might tip, you have to move. Switch sides.” Writers like Myles opened me to consider love not as a fixed, discrete state, but as an oscillation; not as a sovereign kingdom policed by one white knight, but as an ecology; not as a goal-oriented finality, but as an affective intimacy that actively (re)produces the self in relation to others, to otherness, to difference. What if love is a mode of thinking? What if the couplings we form with other people in love become an integer, a unit of difference, for teaching us about our relationships with ulterior agencies, including language?

If the poetic couplet has taught me anything, it’s that love is everywhere—we just need to read between the lines.

My research and creative writing seek to delimit and re-orientate love from a private, individualistic experience toward allocentric connections practiced materially (through bodies) as well as semiotically (through meaning-making). The critical arm of my dissertation articulates coupling as both social and literary analysis—a mode of understanding subject positions as nodes within networks, and a mode of understanding poetry as a kindred site in which these networks play out. I turn specifically to poetry written in the couplet form because couplets, I argue, are inherently relational: two lines modifying themselves by modifying one another, toggling like a switch across their own border and between themselves and the remainder of the poem. The creative arm of my dissertation is a manuscript of love poems written, yep, in couplets. My hope is that, in the embrace of these critical and creative arms, I will attach to more expansive definitions of loving and writing.

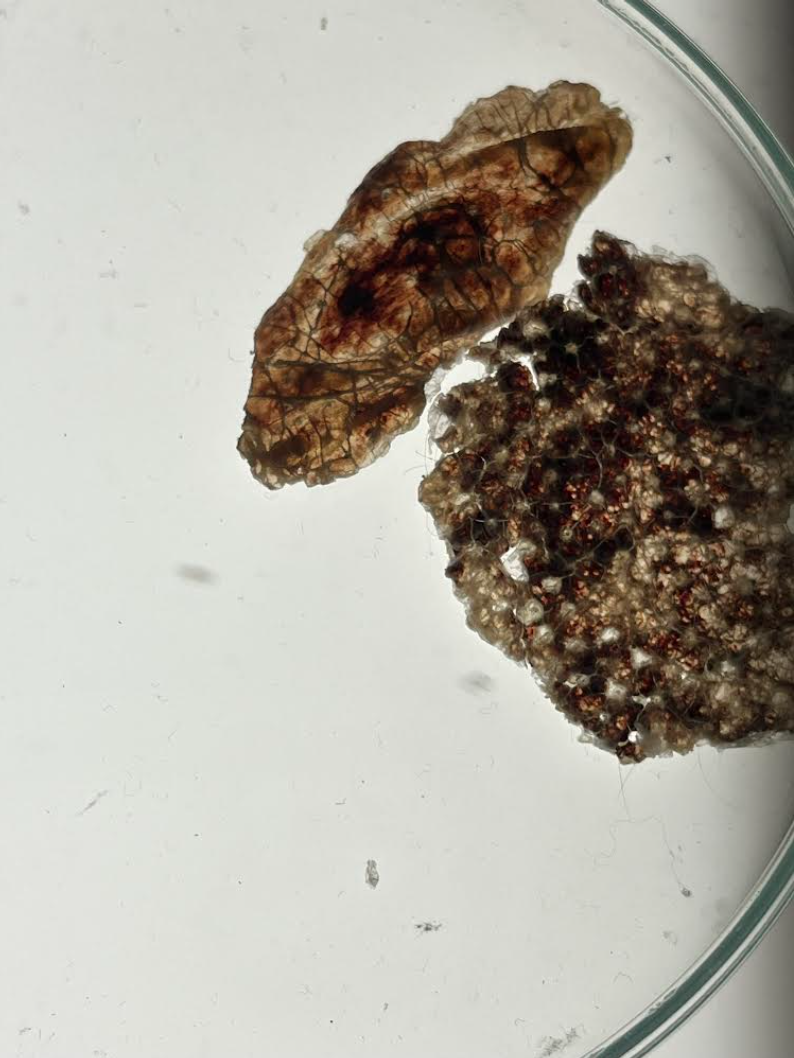

This summer, I read the couplings activated by popular museums uniquely concerned with both form and feeling in their exhibition of personal ephemera from loving relationships—erotic or platonic, active or atrophied—donated by the general public. I mapped, photographed, and wrote poems to the connections between artifact and wall text; between artifact and artifact; between artifact and visitor; between visitor and visitor; and between my own heart, as monitored by an electrocardiogram app, and all of the above. I was interested not only in identifying a proliferation of networked love as documented through relationships and amplified by cultural institutions, I wanted to participate in the new intimacies emerging from the afterlives of recontextualized objects and the publics they assemble. What is even happening as a giddy couple takes a selfie holding hands before the dried elbow scab of another’s ex-lover, backlit like a saint in fluorescent light? What happens to my photo of their photo, taken with consent and now exhibited among the gas station magnets and bill notices on the fridge in my kitchen, where I write this text? If the poetic couplet has taught me anything, it’s that love is everywhere—we just need to read between the lines.

This summer, your theoretical and creative explorations of “coupling” took you to The Love Stories Museum in Dubrovnik and the Museum of Broken Relationships in Zagreb. You have previously described love exhibits as porous spaces that transform private intimacies into public encounters. I’m curious what your personal experience was moving through these museum spaces, and whether you could share a specific material/archival encounter that stands out from these visits? A moment of clarity or wonder, perhaps…

It’s a wonder I didn’t cry more than I did in these intensive sites of expansive love. I kinda wanted to cry when a wedding party erupted from the city hall and passed me where I sat on the Museum of Broken Relationship’s cafe patio, struggling to address my dead friend on one of the promotional postcards scattered throughout the gift shop. I kinda wanted to cry after purchasing a “love lock” from the Love Stories Museum, locating the fence in Dubrovnik where hundreds of rusty padlocks overlook a steep cliff as if threatening to jump, and choosing to take my lock with me, retaining it as an ambient reminder of love’s immutability, its changeability, its multiplicity. But I did cry lugging my bed comforter through the streets of Zagreb, my love artifact for donation. I thought I would feel clever, I thought I would feel like Tracy Emin, frankensteining my own theory of coupling to life in conversation with what Niklas Luhmann terms “reentry” of the form into the form, or the way in which all meaning is produced in relation to other meaning. I would bring this unwieldy form all the way from my Santa Cruz bedroom, and it would connect the fabric of my personal life and my life’s work and the emotional labor of unknown others made new, made flesh as I crossed the threshold of the museum lobby, reentering one form into another like some kind of transubstantiation. But it was not comforting, my unfettered comforter crossed with blood and cum and sweat and saliva and Taco Bell hot sauce, a gift from a former partner where we had slept, and then where I had slept alone. But if love is a technology of communication, and if the spatial partitioning of a museum is another hermeneutics through which it speaks, maybe tears make sense as a kind of embodied speech act—not the case study in porousness I had expected, but maybe the outpouring I needed.

Your work aims to contribute to critical love studies. Can you describe what, for you, is most exciting about this field and how your own work responds, extends, or converses with those ideas? Why is it important now, in this moment of proliferating hate speech, rising rates of hate crimes, and the worldwide spread of fascism, to study love?

I find it exciting, and necessary, that critical love studies situates love in relation to structures of power.

I find it exciting, and necessary, that critical love studies situates love in relation to structures of power. This is not a field of star-crossed lovers at the end of Cupid’s bow—some divine intervention or predetermination—but love shot through with the dynamics of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, and nationality, to name some vectors. However, precisely because of love’s sociocultural proximity, it also has the potential to destabilize our normative lives, and is therefore practice for differentiation and transformative change. Lauren Berlant and Michael Hardt, for example, understand love as already a space of non-sovereignty and urgency: love is where we discuss wanting to become different; love cultivates possibility spaces in which we desire more, rendering ourselves vulnerable and taking risks for a better world, despite the impossibility of knowing exactly what shapes that world will take. I’m also thinking of bell hooks, for whom the classroom is a microcosm of society, a “contact zone” that requires an ethics of love including care, commitment, and trust.

In a time when relationships of all kinds can seem to thrive on the same tenants as neoliberalism (deregulation, flexibility, infinite growth), love’s ability to imagine and to educate renders it also among, in Chela Sandoval’s words, the “cultural and human forms that do not easily slip into either side of a dominant binary opposition. They are the remainder—unintelligible to dominant order.” And it is here, in this unintelligible remainder, in the space of the nonbinary, that I think critical love studies and poetry are united in their refusal to be defined, to be tamed, to reify the power structures which they expose. Guided by discourses in media studies, social systems theory, queer theory, and Black feminism, poetry can further the political project of critical love studies (and vice versa).

Studying love also means I get to do things like take clickbait quizzes to determine my “love language” and still take myself somewhat seriously. My results were inconclusive, like, sometimes I recognize love through gifts? (But also, I give gifts away. To public archives.) So what? Love and poetry are not the possession, consumption, or totalized knowledge of another system. Possession, consumption, or totalized knowledge is fascism: love of sameness and of singular meaning. I’m not suggesting that if we just swiped right more often on Tinder or started more independent presses that the world would be less hateful. But I do think that it is now more important than ever to value difference, and that love and poetry are both models for honoring alterity, even and especially as they decentralize the seat of our own perceived power.

Have you ever said “I love you” into silence? Or encountered a poem you couldn’t grasp? For Douglas Kearney, the uncertain gap between closure and arrival is the disarming stuff of political mobilization. In Mess And Mess And, Kearney writes:

One holds an argument as snake handlers might a diamondback. The rhetorician grips, securely, the scaly collar, ensuring the serpent doesn’t bite.

The poet, however, may find purchase further down the spine, leaving the viper free to writhe, to strike.

If you have ever tried to get comfortable with uncomfortability, you are a lover. If you have ever tried to love another freely for all their unknowable agency, you are a poet.

This summer, you also worked as the Project Manager of the Program Book for the Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music. Can you share what drew you to this position and what you spent the majority of your time working on?

Speaking of uncomfortability and unknowing, I came to the Cabrillo Festival without a background in orchestral music, contemporary or otherwise. Maybe that’s what allowed me to fall so easily in love with the art form and the sociality it engenders. I was, however, moved at first sight by CFCM’s mission statement, which is “to transform the orchestral experience for artists and audiences by building a vibrant community dedicated to the creation and performance of profound, relevant, and innovative music.” Meeting with the close-knit staff of this nonprofit, a Santa Cruz legend and worldwide lodestone, solidified the festival, for me, as not only a culmination of curated concerts featuring new, risk-taking talent, but also a platform to discuss and feel communally through potent topics such as ecological grief, intergenerational trauma, gender oppression, and racialized identity.

As Project Manager of the Program Book, my baseline task was to create a clear and coherent reference for the festival’s performances, open rehearsals, panels, and celebrations. However, this also involved the task of ordering information and editing content such as bios and artist statements to foreground the CFCM’s implied mission of uplifting the voices of diverse composers and musicians—voices that often differ from the majority demographic of older, white, affluent audience members and patrons traditionally invested in contemporary music. I also wrote essays for the CFCM blog, facilitated the Student Staff Program, and worked on the ground as a Production Assistant, all of which invited me to couple with bodies of work and the embodied experiences of community members that make this work possible. In short, I spent the majority of my time collaborating on living poems.

What, for you, is the connection between your work with CFCM, your academic research, and your creative writing and art practice? Why is it important to spend time in so-called “para-academic spaces of artistic expression”? How might you carry your experiences forward?

Delight is what I want to carry forward.

Despite being a specialized field that I had to learn, I connected with contemporary music under the broad rubric of shaping narratives and building community—an anticapitalist rubric that poetry shares. At the recent All-In conference on co-creating knowledge for justice organized by the UCSC Institute for Social Transformation, my colleagues Angel Dominguez, Melissa Mack, and Kristen Nelson posited art-making as inherently a radical site of resistance because it causes us to slow down, to engage, to think and feel deeply, in effect jamming the machine of solvent productivity and uncritical automation like Luddites in the textile mill. This, too, is the space of excess, of remainder, of imminent desire, of illegibility to power cultivated by music, by poetic language, by love. As my research in love museums revealed, excess exceeds institutional borders. If I take coupling seriously as the proliferation of difference with traction as an aesthetic device and a mode of being in the world, coupling with para-academic spaces of artistic expression is not an option, but a necessity. I am grateful to CFCM for the occasion to interview Valerie Joi, whose research focuses on music as a tool to deepen cultural humility and cross-cultural communication. Joi’s research also exceeds academia to influence the way she guides her personal life with radical love as an inseparably political and spiritual initiative. I didn’t foresee the resonances between Joi’s practices and my own, but that is the delight of coupling, when the unit of difference is the ecology of relation. Delight is what I want to carry forward. One day, I might be delighted to find that we no longer categorize “love poems” based on what their content expresses, but on what their forms do.

Banner Photo: Hold and hole: love lock fence, Dubrovnik, Croatia