Grad Profile: Matt Polzin

Matt Polzin is a PhD candidate in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. Polzin’s research applies the concept of queer temporality to Feminist, Queer, and Trans Speculative Fiction in order to reveal how temporal play makes space for more generative forms of collectivity. In October, we learned more about Polzin’s dissertation project and summer research. Polzin received a 2022 THI Summer Research Fellowship to support their archival research in England. They are also a 2022 Fellow in the Social Science Research Council-Dissertation Proposal Development Program. We discussed Polzin’s research experiences at the British Library and London School Economics’ Special Collections, the relationship between speculative fiction and medicalized knowledge, and the legacies of early 20th century queer utopian fiction on our contemporary understandings of the gender binary and coalition-building.

Matt Polzin is a PhD candidate in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. Polzin’s research applies the concept of queer temporality to Feminist, Queer, and Trans Speculative Fiction in order to reveal how temporal play makes space for more generative forms of collectivity. In October, we learned more about Polzin’s dissertation project and summer research. Polzin received a 2022 THI Summer Research Fellowship to support their archival research in England. They are also a 2022 Fellow in the Social Science Research Council-Dissertation Proposal Development Program. We discussed Polzin’s research experiences at the British Library and London School Economics’ Special Collections, the relationship between speculative fiction and medicalized knowledge, and the legacies of early 20th century queer utopian fiction on our contemporary understandings of the gender binary and coalition-building.

Hi Matt! Thanks for chatting with us about your ongoing research. To begin, could you give us a general synopsis of your dissertation project and, more specifically, the research you have done this summer?

My dissertation, “Screwing With Time: Feminist and Queer Utopian Fiction, From the Turn of the 20th Century to Now,” focuses on feminist and queer literary utopias. I consider how the progressive temporalities of 19th and early 20th c. Anglophone feminist utopian fiction are tied to racial capitalist and colonial orderings of space, time, and matter. By bringing the concept of queer temporality to utopian literature, I also consider how authors working in the areas of feminist and queer science fiction, Afro-futurism, and alternate history screw with time in ways that critique those future-oriented progressive temporalities and imagine forms of collectivity that are elided by them. I’m also a creative writer, and with my fiction practice, I play with the relationship between temporality and utopia, thinking about how past queer communal projects can offer us tactics in the present.

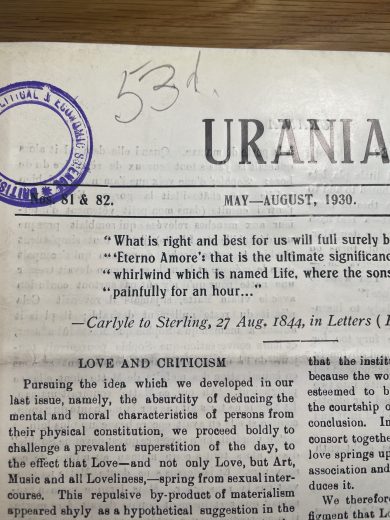

This summer, much of my research focused on the utopian writing of Thomas Baty/Irene Clyde (1869-1954), a British international law scholar and radical feminist writer. Baty/Clyde published works using both names. While most of their radical feminist writing appears under the name Irene Clyde, they continued publishing the feminist journal Urania (1916-1940) under the name Thomas Baty until its last issue. I focused on Irene Clyde’s 1909 utopian novel, Beatrice the Sixteenth, which is about a genderless, asexual utopian society, their 1934 essay collection Eve’s Sour Apples, and their contributions to Urania.

You spent time this summer doing research at the British Library and London School Economics’ Special Collections. I imagine this archival research revealed a host of fascinating documents, histories, and stories, but was there a specific text or a specific moment that stands out to you from your research–a moment of surprise, shock, awe, or understanding you’d like to share with us?

I love this question, especially because I felt such a range of emotions when doing this research. I think it might be helpful to share two moments. Both concern Clyde’s utopian novel, Beatrice the Sixteenth (1909) In the novel, a British doctor, Mary Hatherley, is traveling through the Arabian peninsula when she is suddenly transported to an ‘alternative realm of space’ containing a genderless and asexual utopian nation-state called Armeria. Soon after arriving, she realizes that the two words for people that she thought were gendered, kyné and anra, turn out to be interchangeable, and her companion Ilex explains that the Armerians altogether lack gender distinctions. Soon after, Mary thinks, “And it was pleasant . . . to lean one’s perplexed head on Ilex’s shoulder as the arm passed round one’s waist invited one. He or she, it was consolatory, all the same!” Here, Clyde uses the indefinite pronoun to avoid having to gender Ilex. Throughout the novel, it was exciting to see Clyde’s strategies for retooling language in order to adequately represent the speculative world.

Something else to bring up is how Clyde’s utopian novel, Beatrice the Sixteenth, is in many ways a colonial fantasy about abolishing sex, both in terms of sex distinctions and the sex act. One of the questions that arises is, How does a community without procreation sustain itself into the future? What does reproduction look like? Clyde resolves this problem by having the Armerians trade with a neighboring ‘barbarian’ community for babies. This community is regarded as a ‘lower strata’ of humans, and their babies are forcibly assimilated into Armerian society. Here, the non-binary, asexual utopia is supported by an ongoing act of expropriation, one that also functions as form of population control. I think it’s important to remember that while many of these feminist utopian visions strive for more livable worlds, they can also be enmeshed in systems of colonial and racialized violence.

Your work also aims to explore contemporary coalition-building amongst cis, trans, and non-binary feminists. How do you understand the relationship between archival research, literary criticism, and social activism?

One thing that is significant about Clyde’s reimagining of gender is that it occurs prior to and outside of the consolidation of medicalized definitions of transsexuality, emerging instead in the context of radical feminist organizing in Britain. Thomas Baty co-founded the radical feminist journal Urania with a group of British and Irish suffragists in 1916. For this group, refusing the sex/gender binary was linked to the fight against the oppression of women. By rejecting the identificatory apparatus of the binary altogether, the editors broadened the kinds of coalitions that occurred under the term feminism and whose bodies were conjured by the term feminist, which makes this work especially important to the history of trans feminism. The publishers write, “Urania denotes the company of those who are firmly determined to ignore the dual organization of humanity in all its manifestations. . . There are no ‘men’ or ‘women’ in Urania.” In every issue, the journal included snippets from other newspapers documenting instances of gender insubordination, including cross-dressing, queer relationships, and women taking on masculine lines of work. The journal used these experiments in living from the recent past as grounds for envisioning a future trans feminist community, one that it helped usher into being through its publication.

What can the study of early trans figures like Irene Clyde–including their critical writings against the gender binary in Urania and their utopian novel Beatrice the Sixteenth–teach us about contemporary conceptions of gender plasticity, radical embodiment, reproduction, and community-building?

Past projects of hope that reimagine gender can invigorate current efforts to push against the boundaries of binaristic logics, highlighting the ways that the categories of gender and sexuality are malleable.

If Clyde comes across as a radical visionary, it is in part because of their determination to dispense with the categorical markers of gender binary altogether, recognizing how dualistic thinking forecloses a multiplicity of experiences. Clyde conjectured that sex would likely vanish from society, citing how more and more people were transgressing its boundaries and arguing that developments in scientific research proved that sex was not fixed. For instance, in a chapter of Eve’s Sour Apples called “The Vanishing Sex,” Clyde references Eugen Steinach’s research on hormones and the mutability of sex in guinea pigs as well as sex changes in oysters, pointing out how humans were “within a measurable distance” to achieving “such a metamorphosis.” Clyde’s writing on this matter is important as it gives us a trans perspective on early endocrinological and sexological research, which is very different than that of medical practitioners. As scholar Jules Gill-Peterson has shown, in the early days of intersex and trans medicine, doctors would engage the plasticity of the body in order to impose a sex that adhered to the sex/gender binary. Clyde, on the other hand, believed that this research undermined that binary altogether.

The past year has seen a proliferation of anti-trans legislation particularly concerning the capacity of the state to intervene in youth transitioning. How does this hostile political climate affect your work and why is it important, now, to revisit historical speculative fiction concerning gender?

Past projects of hope that reimagine gender can invigorate current efforts to push against the boundaries of binaristic logics, highlighting the ways that the categories of gender and sexuality are malleable. Clyde’s Beatrice the Sixteenth (1909) is a precursor to works of speculative fiction like Theodore Sturgeon’s Venus Plus X (1960), Ursula K Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness (1969), and Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy (1987-89), all of which give us glimpses of worlds that do away with or upend the organizing binary of gender and reconfigure reproduction. I think it is important to note that works of feminist utopian fiction from the turn of the 20th century like Clyde’s Beatrice the Sixteenth also demonstrate some of the potential pitfalls in taking on one form of oppression at a time. In only looking forward to a better, more perfect future society through the abolition of gender, Baty/Clyde relied on other classificatory systems, including colonial hierarchies. Utopian worldmaking benefits when we enhance our ‘response-ability’ to past acts of racialized and colonial violence and account for existing cultural and ecological relationships in places, especially those “elsewheres” that the genre of utopian fiction has historically treated as blank slates for the imagination. Approaching these historical feminist and queer literary utopias with multiples lenses can help us imagine what allyship and coalition-building across uneven forms of oppression can look like.

Finally, how has the THI Summer Dissertation Fellowship and the SSRC-DPD program helped you in your research and writing process?

My peer group and mentors in the SSRC-DPD program helped me craft the set of questions I would bring to the texts and introduced me to a number of strategies for organizing my materials while in the archive.

If it hadn’t been for THI and the SSRC-DPD program, I wouldn’t have been able to complete my library and archival work on Thomas Baty/Irene Clyde. Although the utopian novel Beatrice the Sixteenth will likely be reissued next year, Baty/Clyde’s books have long been out of print and only a few copies are available, which meant that I needed to travel in order to read them. Additionally, my peer group and mentors in the SSRC-DPD program helped me craft the set of questions I would bring to the texts and introduced me to a number of strategies for organizing my materials while in the archive. I’m really grateful for the support.

Banner Photo captured at The British Library